by Richard Turnill, Global Chief Investment Strategist, Blackrock

The price of oil has surged in 2018. Richard explains our take on how to play the rally.

A rise in Persian Gulf-related geopolitical risks has helped fuel double-digit gains in oil this year. A favorable supply-demand picture has provided additional juice, making oil a top-performing asset class in 2018. For investors seeking exposure to oil now, we see more appeal in energy equities than in the commodity.

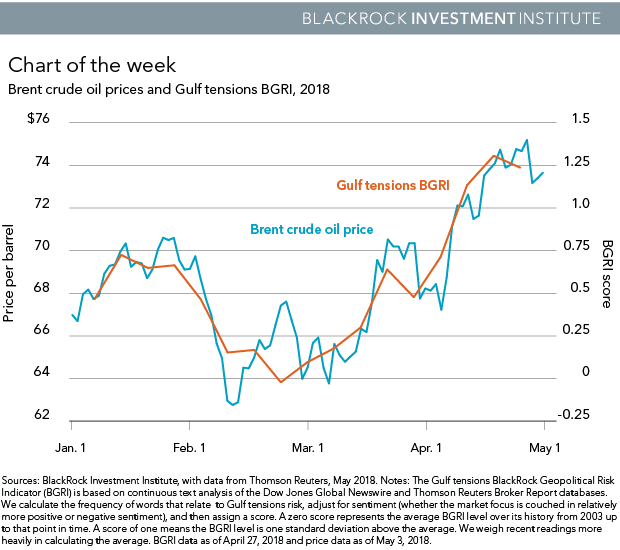

This year’s spike in the oil price coincides with rising concerns about Persian Gulf tensions. This is reflected in a proprietary BlackRock indicator that scrapes the text of broker reports and financial news articles to assess the market’s attention to the risk. See the orange line in the chart below.

Investors today appear to be pricing in potential for supply disruptions if the U.S. does not extend its waivers on Iran oil sanctions–and worries over proxy wars in the Gulf region. This geopolitical risk premium comes amid OPEC production cuts and firming global demand for oil thanks to the global expansion. It also may explain why recent higher oil prices have not been associated with strong performance in other risk assets, a break from the past two years.

A stronger case for energy equities.

We see today’s backdrop of heightened Gulf tensions, supply constraints and steady global economic growth persisting. Geopolitical tensions in the Middle East could flare further in the near term, particularly between the U.S. and Iran (see the Week ahead). Oil supply could also tighten if OPEC extends production cuts in June, or Venezuelan production falls further. Yet the rise in oil prices we have seen so far is unlikely to pose a significant drag on the global economy and its impact on core inflation should be minimal, we believe.

Read more market insights in my Weekly Commentary.

For investors seeking exposure to oil today, we see a stronger case for investing in energy equities over crude itself or energy-related debt. Oil prices have run well ahead of energy stocks this year but this trend has started to turn. One factor supporting energy firms: their focus on capital discipline, evident in first-quarter earnings results. Unlike in some past oil market rallies, companies are not making huge investments in future production. Instead, they are using free cash flow to return capital to shareholders via increased buybacks and dividends.

Risks to our view.

A hefty drop in oil prices, possibly sparked by a large U.S. shale production boost or falling demand. Oil futures have lagged the rise in spot prices, indicating the supply/demand balance may be more challenged in 2019. Further U.S. dollar gains could also weigh on oil–with a knock-on to related assets–if the historical negative correlation between the dollar and oil prices reasserts itself after a recent breakdown.

The good news.

Current oil prices offer potential upside for energy companies’ earnings and stock prices. Most energy companies have budgeted for mid-$50s oil prices in 2018, with this conservative outlook reflected in share prices today. This points to valuation upside should current levels of oil prices be sustained. In energy equities, we like exploration and production firms and midstream companies. We also see some opportunities in emerging market (EM) energy stocks.

Richard Turnill is BlackRock’s global chief investment strategist. He is a regular contributor to The Blog.

Copyright © Blackrock