by Liz Ann Sonders, Senior Vice President, Chief Investment Strategist, Charles Schwab & Co

Key Points

- The yield curve has been flattening and the 10s-2s spread hit a low of 41 basis points last week, raising concerns.

- Although ample headlines have warned about imminent threats of an inversion and subsequent recession, history shows long lag times and healthy stock market performance.

- Large caps could resume their outperformance if yield curve history is any guide.

The spread between the 10-year Treasury and 2-year Treasury yields has narrowed to below 50 basis points, with countless media headlines raising alarm bells and warning about an impending inverted yield curve and possible subsequent recession.

First a primer

The yield curve is a graphical plot of the yields of bonds with different maturities; and the aforementioned “10s-2s” spread is one of the more commonly-tracked. In a normal economic/market environment, the curve is generally upward-sloping as yields on longer-term bonds are typically higher than shorter-term bonds, because the former are higher-risk investments due to their duration.

An inverted yield curve occurs when shorter-term rates are above longer-term rates. This happens when the Fed hikes the fed funds rate to beyond the yield of longer-term Treasury securities; and has been a fairly accurate recession signal historically, albeit with a lag.

What say you Fed?

The topic has become a hot one at client events at which I’ve spoken recently. Investors are worried. But want to know who are, for the most part, not worried? Federal Reserve (Fed) officials:

- Philadelphia Fed’s Pat Harker (and my friend and former President of my undergraduate alma mater, University of Delaware): “I’m also keeping an eye on the yield curve. I think worries so far have been a little inflated.”

- New York Fed’s William Dudley: “I am not concerned about the recent flattening of the Treasury yield curve.”

- Chicago Fed’s Charles Evans: “Yield curve not nearly as much of a concern as I might have pointed to a couple of months ago.”

- San Francisco Fed’s John Williams: “The flattening of the yield curve that we’ve seen is so far a normal part of the process, as the Fed is raising interest rates, long rates have gone up somewhat—but it’s totally normal that the yield curve gets flatter.”

- Cleveland Fed’s Loretta Mester: “I just think long rates are going to go up given where we are in the economy and given where we see the economy going. But this is another reason why we need to keep raising up the short rate.”

- Fed Vice Chair for Supervision Randal Quarles: “I’m not viewing the current flattening of the yield curve as much of a signal toward an impending recession.”

- The big kahuna, Fed Chair Jerome Powell: “[Although] there are good questions about what a flat yield curve or inverted yield curve does to intermediation…I don’t think that recession probabilities are particularly high right now.”

But there are a few Fed officials who feel a bit less sanguine about the yield curve’s flattening:

- St. Louis Fed’s James Bullard: “Yield curve inversion remains a possibility this year.”

- Dallas Fed’s Robert Kaplan: “Flat yield curve tells me the bond market sees sluggish growth.”

- Minneapolis Fed’s Neel Kashkari, who consistently voted against rate hikes last year, said in a recent CNBC interview that the flattening curve was “a yellow light flashing”—a warning that the Fed should halt rate increases or risk slowing the economy too swiftly and bringing on a recession.

As per the latest meeting minutes, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) “generally agreed that the current degree of flatness of the yield curve was not unusual by historical standards.”

Looking at history for guide to stock market’s path

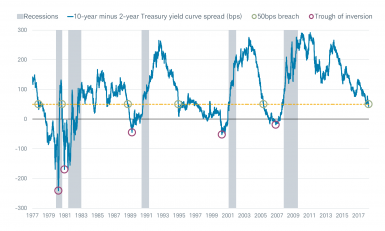

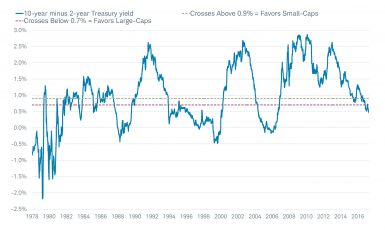

Since the aftermath of the “great recession”, the yield curve has flattened from nearly 300 basis points to less than 50 basis points (hitting a low of 41 basis points early last week). You can see a long-term chart of this spread below.

Yield Curve Flattening

Source: Charles Schwab, FactSet, as of April 20, 2018. Bps=basis points.

The yellow dotted line on the chart is at 50 basis points, the spread recently breached, triggering much of the recent consternation. The green circles on the chart show periods in the past when 50 basis points was breached en route to an inversion (assuming the economy wasn’t already in a recession, like in 1981). For what it’s worth, the average span between the green circles and the subsequent recession was 33.6 months (the median was 29 months).

The red circles on the chart show each of the subsequent inversions at their maximum inverse spread (i.e., the inversion trough). For what it’s worth, the average span between the red circles and the subsequent recession was 20.2 months (the median was 18 months). In other words, even after the yield curve inverts and gets to its deepest inversion, there has remained a reasonably long runway ahead before the next recession.

Of course, equity bear markets tend to begin in advance of recessions; which is perhaps why investors are getting nervous about the curve’s flattening. There are myriad reasons for a bit more caution about stocks this year, which we highlighted in our “It’s Getting Late” 2018 outlook; but an imminent inversion of the yield curve is not one of them.

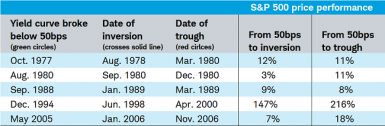

The table below refers to the prior chart and looks at the stock market’s performance in the aftermath of the curve flattening to sub-50 basis points. I looked at both the span between breaching 50 basis points and the point of inversion, and the span between 50 basis points to the trough of the inversion.

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, FactSet, as of April 20, 2018. Bps=basis points.

As you can see, during both of these phases historically, the stock market had positive returns—in every case. Inverted curves have tended to lead bear markets, but often with a substantial lag. But not all bear markets were preceded by inverted curves. That’s why only looking at the yield curve doesn’t yield strong conclusions across all market environments.

As my friend Joe Kalish at Ned Davis Research recently shared in an e-mail, “The outlook for inflation, credit, monetary policy, and the economy are more important for determining the direction of the stock market than the shape of the yield curve, especially after a period of heavy manipulation by the central banks.”

Large caps’ optimal range?

We have had a large cap bias within the U.S. stock market for more than a year, during which time small caps have had two distinct relative rallies: the first was last September when hopes for tax reform lifted; and the second has been since the eruption of the “tariffs tif.”

The September rally faded when the details of tax reform were released and the change to interest expensing was seen as detrimental to smaller companies, given their higher debt levels generally. But the latest rally has had some legs during the tariffs-related volatility due to smaller companies’ generally more domestic orientation.

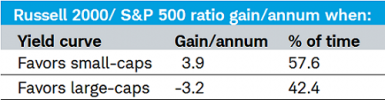

But the yield curve has also historically affected the relative performance of small caps vs. large caps, as you will see in the pair of charts and accompanying table below.

Small Caps Relative to Large Caps

Source: Charles Schwab, FactSet, Ned Davis Research, Inc. (Further distribution prohibited without prior permission. Copyright 2018 (c) Ned Davis Research, Inc. All rights reserved.), as of April 20, 2018.

As you can see in the second chart above, the yield spread recently breached the level below which large caps have outperformed small caps historically, as seen in the table.

Small-cap banks make up more than 20% of the Russell 2000 Index, so a flattening curve generally has a detrimental impact on those companies. In addition, the aforementioned generally higher debt level of smaller companies means they’re disproportionally hurt by higher rates. Finally, weak credit fundamentals and higher equity market volatility are likely to amplify the impacts.

In sum

I find myself siding with the more benign views expressed by Fed officials about the flattening of the yield curve. We’ve had earnings recessions without economic recessions historically; but we’ve never had an economic recession with earnings growing as sharply as they are today. However, a Fed which is likely to raise rates three-to-four times this year coupled with now-tightening financial conditions and the flattening of the yield curve are likely to keep volatility elevated.