by Marina Pomerantz, Portfolio Manager, Trimark Investments, Invesco Canada

In a previous post I discussed the data privacy concerns that affected the valuations of several U.S. internet companies in the aftermath of the Facebook/Cambridge Analytica scandal. In this post, I will focus on several upcoming regulatory changes as part of the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which are set to be implemented in May 2018.

What is GDPR?

The GDPR framework is a new regulatory directive that aims to provide European residents with more control over their personal data. The framework governs the means through which personal data can be collected in physical and digital settings, and stipulates how users can grant consent to organizations for data collection.

Under the terms of GDPR, businesses and other organizations must ensure that personal data is gathered legally and under strict conditions. Furthermore, those who collect the data and manage it will be obliged to protect it from misuse and exploitation, or face penalties for not doing so. GDPR violations could result in penalties of €20 million or 4% of global annual revenue (whichever figure is greater).

It’s worth noting that the idea for these regulations was first proposed in 2012, and that it took 4 years to reach agreement about the final implementation of the GDPR directive. As such, investors should keep in mind that it is not easy to make further amendments to the GDPR provisions without extensive further consultation and debate.

Assessing the potential impact

As discussed in my previous post, it’s clear that internet platforms like Alphabet, which collect data about users’ internet activity to target advertising more efficiently, could see an impact to their business models. There are several areas of impact to consider that are most relevant to internet companies:

- If consumers will be able to edit, transfer or delete the data that has been collected about them, there is potential for the datasets of the internet companies to decrease in size over time, making the predictive algorithms that these companies use for ad targeting less effective.

- Companies will have to provide a clear explanation and outline the legal basis on which they are collecting and processing consumer data. If internet companies – or the third party developers to whom they make data available – cannot come up with a legitimate reason for needing the data, they could face prosecution.

- Companies will have to obtain explicit consent from consumers to collect personally identifiable information (PII), like date of birth, social security numbers, etc. This would affect internet platforms that merge their own user datasets with those provided by third-party data services like credit bureaus.

- Companies that collect data and then cleanse it of personally identifiable details (i.e., companies that generate cookies that track users’ web browsing activities) must clearly notify users that they are collecting this data and obtain consent by having the user agree to terms and conditions, or continue to use their product after being notified of ongoing data collection.

While the ultimate impact remains several months away, encouraging developments suggest Alphabet and many other companies could manage the regulatory outcomes of GDPR, and largely preserve their business models. These developments include:

- Popular platforms like Google, Facebook, LinkedIn and Twitter have already begun updating their terms and conditions to become GDPR-compliant and ensure that users are fully aware of their data collection, storage and sharing practices. Privacy controls that enable users to opt out of data collection have been featured more prominently in the account settings pages of many popular apps. In addition, mobile and desktop web browsers like Android’s Chrome have started implementing notifications and prompts that alert the user to data collection on the website and obtain consent before the user can view content.

- In order to reduce collection of PII, Facebook and other internet platforms have begun to gradually phase out their usage of third-party datasets provided by the likes of credit reporting agencies and payment networks. Going forward, internet platforms will dedicate more resources toward scrubbing cookies and users’ anonymized data profiles of any data that can be constitute PII.

- The GDPR provisions contain a “legitimate interest” provision that exempts companies from getting consumer consent for data collection if the data allows the company to offer help to the consumer. It remains to be seen how these exceptions will be enforced, but we could envision a scenario where, for example, geo-location data could be exempt if it provides users with information about accidents and traffic blockages in mapping/navigation software. A key distinction is whether the data collected by the application is specifically related to improving the content or functionality that the end user is requesting from the app. To prove this, internet companies will need to provide more specific information about how data collection helps them improve the functionality of their apps and services beyond using vague terms like “improving user experience.” With proper documentation these exceptions could apply to the collection of user search history to allow search engines to provide more relevant search results, for example.

- Due to changing consumer habits, the majority of the ad revenues for large internet platforms are now obtained from mobile devices. For example, Google and Facebook derive over 50% and 80% of their revenue from mobile,1 respectively, and these proportions are expected to continue rising over time. To access these popular mobile apps, most consumers install them on their phones and provide explicit consent to enable these apps to collect data. Because mobile apps already require opt-ins from consumers, many internet companies should be able to make the case that they already possess consumer consent for their data collection activities, provided PII-type data isn’t collected inadvertently.

- A key feature of GDPR is that permissions must flow down the digital advertising value chain. This means that not only must large platforms like Facebook and Google obtain user consent, but so too must the advertising technology companies who auction off ad space and advertisers who purchase ad impressions. Many of these platforms do not have direct consumer interactions and will be reliant on their partnerships with large internet players to obtain the necessary permissions. This could further entrench the role of internet platforms like Google as a key means through which consent is obtained.

- Finally, GDPR does not require companies to collect user consent if no user data is used in ad targeting. Put differently, if internet platforms only display “contextual” ads that match the actual content on the website or app where the ad appears – without refining the ad for any of the user’s personal details – then they can bypass the consumer opt-in process before showing ads to a user who visits one of their sites. This would be equivalent to Google displaying an advertisement for a skiing brand on a website for winter sports enthusiasts – in this case, the placement of the ad is dictated by the content of the site and the ad may be shown to users who visit the website even if their personal data history does not suggest they like skiing. Because its history as a search engine involves substantial cataloguing of website metadata through web “crawlers”, Google has a lot of flexibility to adapt its AdWords service to only include contextual data from websites, and in this case it could significantly reduce the GDPR user consent requirements for a large part of its business. This would likely not be a first choice for Google because doing so could cause a decline in its advertising revenue, as advertisers will be less willing to pay more for untargeted ad impressions. Nevertheless, this alternative should prevent a very significant erosion in the company’s business.

Conclusion

The biggest risk from GDPR is that consumers will opt out of data sharing altogether, or have their data deleted. As I discussed in my previous post Web stocks, user data abuse and regulation, this scenario appears unlikely given the substantial utility that consumers derive from the services offered by many popular internet platforms.

The team continues to believe that diversified internet platforms like Alphabet offer a range of services that are valued by consumers enough for them to consent to an ad-supported model, and that these companies can achieve GDPR compliance through improved customer transparency, clearer documentation about data usage purposes, and careful limitation around collection of PII.

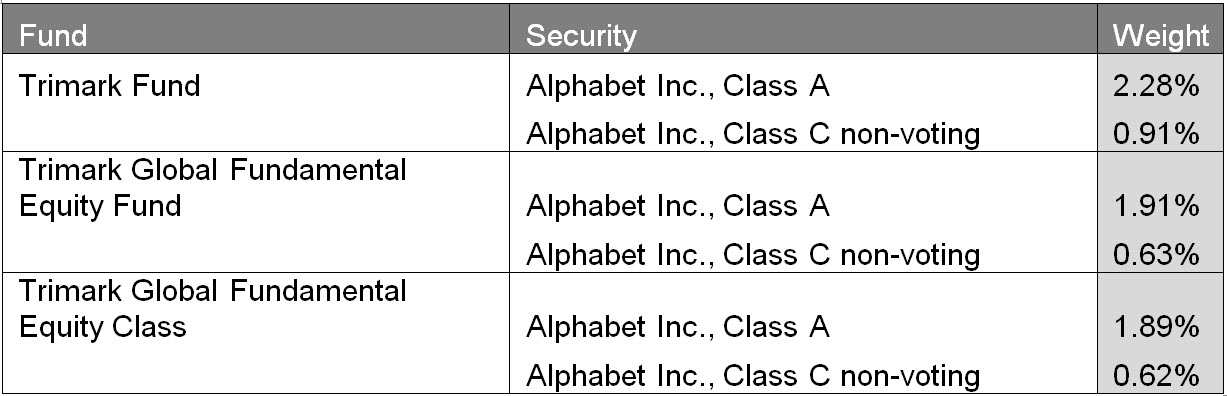

Holdings of Alphabet as at March 31, 2018

This post was originally published at Invesco Canada Blog

Copyright © Invesco Canada Blog