by Scott Brown, Ph.D., Economics, Raymond James

Recent stock market volatility was partly blamed on fear that inflation will soon “take off.” Simple supply and demand arguments would suggest that pressure on resource markets (labor mostly, but also raw materials) would lead inflation higher. Many of us old-timers remember the Great Inflation of the 1970s and early 1980s. However, such fears are overblown – at least for the foreseeable future. Still, there are plenty of other things for market participants to worry about.

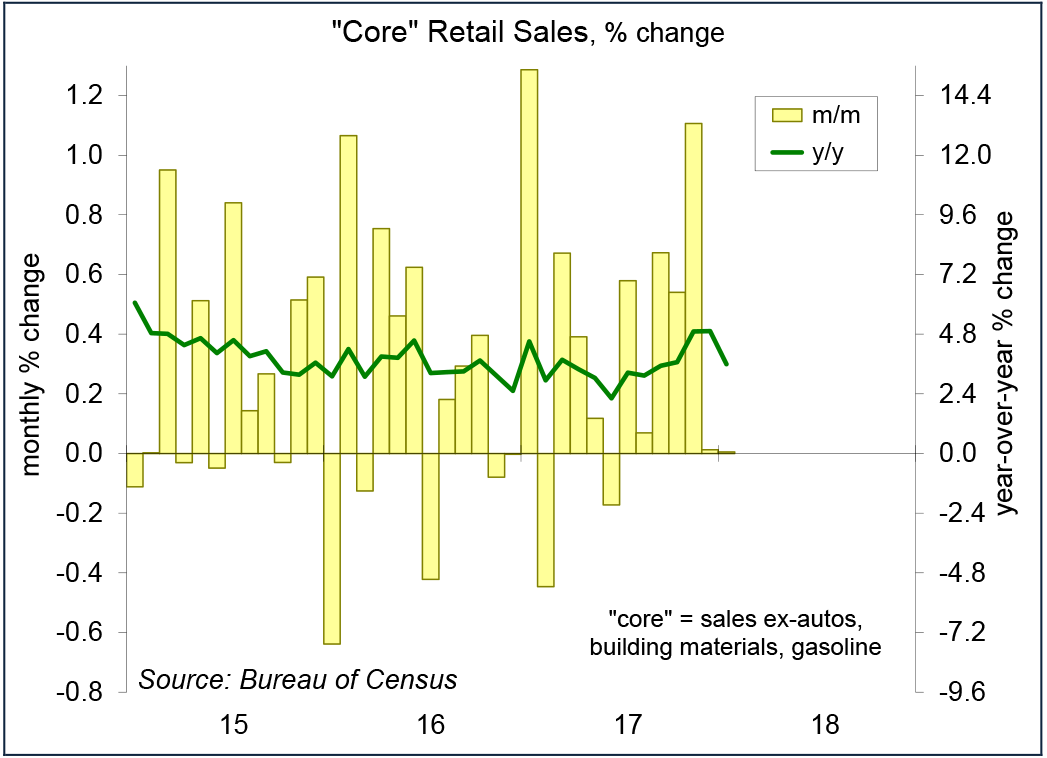

Retail sales results for January were weaker than expected and figures for November and December were revised a bit lower. None of that should be too worrisome. Seasonal adjustment can be tricky, but adjusted retail sales figures normally move in fits and starts. A moderate slowdown in consumer spending growth would not be unusual following a strong 4Q17 (which partly reflected a rebound from a soft 3Q17). Similarly, industrial production was softer than expected in January, but that followed a strong showing in the fourth quarter (which also reflected a rebound from a soft 3Q17).

The inflation of the 1970s and 1980s is typically blamed on the oil shocks. However, the mechanism driving inflation was different than it is now. The government began indexing Social Security to the Consumer Price Index in the early 1970s. The unions saw that as a great idea and many incorporated it in their labor contracts. So, a sharp rise in oil prices boosted the CPI, which lifted union wages, and non-union wages followed. Inflation became embedded in the labor market. You needed a recession in the early 1980s to wring inflation expectations out of the system. Over 25% of private-sector jobs were union jobs in the early 1970s. We had 424 work stoppages in 1974 and averaged 289 per year in the 1970s. In 2017, 6.5% of private- sector jobs were union. We had seven work stoppages last year, the second lowest on record (we had five in 2009).

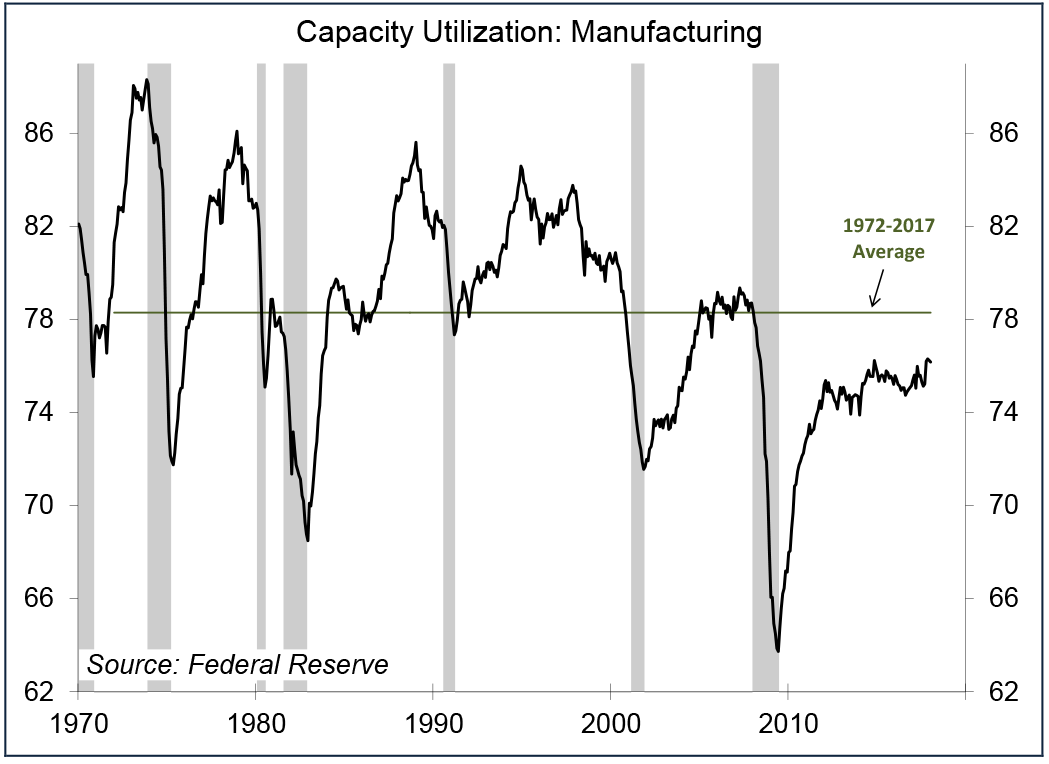

The 1970s also experienced bottleneck pressures in production. High levels of capacity utilization were associated with rising costs of goods. The rule of thumb was that anything above 85% would add significantly to inflation. Coincidentally, these episodes hit at about the same time as the oil shocks. In recent years, capacity utilization has been below its long-term average. Firms are not struggling to keep up with demand.

Of course, a lot of the production of consumer goods has been moved outside of the U.S. over the last few decades. As a consequence, we see much smaller inventory swings domestically, and low and relatively stable inflation. The Federal Reserve does not respond to exchange rates, but does need to take into account the inflationary implications of movements in the dollar. Yet, the relationship between the dollar and import prices appears to be disconnected. Over the last year, we’ve seen a pickup in inflation in imported raw materials (which is more reflective of a strengthening global economy than a softer dollar), but very little inflation in finished goods (capital equipment, autos, and other consumer goods).

Over the last year, the tight labor market has not generated the kind of wage inflation seen in previous periods of prosperity. The likely explanation is that wage bargaining power has shifted dramatically toward firms. Union membership is low. Large firms have much greater power in setting labor compensation.

The Fed still views inflation as being driven primarily by two factors: inflation expectations and the labor market. The central bank will continue to monitor market-based and survey-based expectations of inflation, but many Fed officials will grow increasingly anxious about the job market.

On balance, the available data still suggest that inflation is unlikely to be much of a problem over the next couple of years. Increased government borrowing, on the other hand, is likely to have a bigger impact on the bond market.

*****

The opinions offered by Dr. Brown should be considered a part of your overall decision-making process. For more information about this report – to discuss how this outlook may affect your personal situation and/or to learn how this insight may be incorporated into your investment strategy – please contact your financial advisor or use the convenient Office Locator to find our office(s) nearest you today.

All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the Research Department of Raymond James & Associates (RJA) at this date and are subject to change. Information has been obtained from sources considered reliable, but we do not guarantee that the foregoing report is accurate or complete. Other departments of RJA may have information which is not available to the Research Department about companies mentioned in this report. RJA or its affiliates may execute transactions in the securities mentioned in this report which may not be consistent with the report's conclusions. RJA may perform investment banking or other services for, or solicit investment banking business from, any company mentioned in this report. For institutional clients of the European Economic Area (EEA): This document (and any attachments or exhibits hereto) is intended only for EEA Institutional Clients or others to whom it may lawfully be submitted. There is no assurance that any of the trends mentioned will continue in the future. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

Copyright © Raymond James