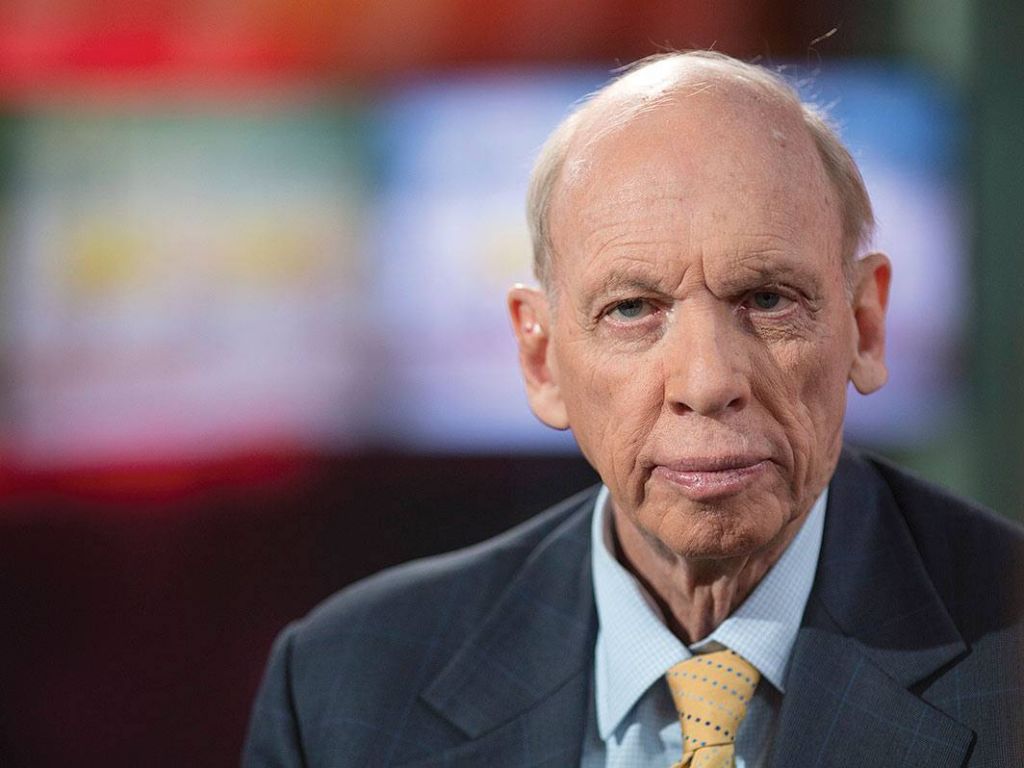

by Byron Wien, Vice-Chairman, Blackstone

In my conversations with institutional investors I find a surprising lack of optimism about the outlook for equities. The capitalization-weighted Standard & Poor’s 500 was up over 11% year-to-date, excluding dividends, on September 18. Some would argue that only a few stocks are accounting for the rise, but the equal-weighted S&P 500 was up over 8% year-to-date as well. Everyone is aware that the economic expansion and the bull market have continued for a long time. Equities bottomed in March of 2009 and the economy began to strengthen in June of that year, so we have been in a favorable period for investing for more than eight years. Cycles usually do not last this long. We all know it can’t go on forever, but I believe we could continue on a positive course for both the economy and the market for several more years.

The principal reason for this conclusion is that the usual factors that warn of a bear market or recession are not evident. What would really worry me would be an inverted yield curve, but there is now almost an eighty basis point spread between the two-year Treasury and the ten-year. I would also be concerned if retail investors were euphoric about equites as they were in 1999 or 2007. They are generally optimistic, but not excessively so, although earlier this year sentiment did rise to a worrisome level. Investors large and small are also leaning toward the defensive. Hedge fund net exposure clearly shows a mood of caution: it is just under 50% now; it was mostly 55%–60% in the 2000–2008 period. Individuals are still buying bond funds even at these low yields because of their lack of confidence in the stock market. Institutions, in their desperate search for yield, have bid up the price of lower-quality bonds to the point where their spread with Treasurys is historically low. Warnings of trouble ahead, however, would usually be associated with high spreads. Maybe investors are too complacent, but this may not be the case if the economy continues to grow.

We know that the Federal Reserve was considering an additional increase in the federal funds rate in September, but was discouraged from taking any action by hurricanes Harvey and Irma. The planned shrinkage of the Federal Reserve balance sheet was probably also delayed for the same reason. The S&P 500 has also shown a tendency to peak after each rate increase by the Federal Reserve and we have only begun the tightening cycle now. The hurricanes are likely to reduce third-quarter real GDP growth by at least one-half of one percent, but demand driven by rebuilding should be reflected positively in the fourth quarter and the first quarter of 2018.

Another important warning signal is the Leading Indicator Index, which has been climbing steadily since 2016. Recent data shows the possibility of a growth slowdown but a continuation of the expansion. The slowdown, if it comes, may trigger a correction in the equity market, but the present steep slope of this indicator suggests nothing more serious than that. Based on this data, even when the Index tops out, we would still have as long as two years for the market to work its way higher before the downturn begins. Corporate earnings are still increasing and there has never been a recession while that is happening.

Strong business activity exists not only in the United States, but throughout the world: Europe should grow at close to 2% this year; so will Japan. The rates for China, and India will be close to 7%. The U.S. will benefit from continued strength in these key areas. One condition that invariably appears before a recession is an increase in cyclical spending as a percentage of GDP. This indicator has exceeded 28% before every recession going back to 1970 but is only at 24% now. Perhaps there is a secular shift in spending patterns toward non-cyclical services rather than goods that accounts for the drop, but we still should expect a pick-up in cyclical spending before the end of the cycle. Another factor dampening capital spending is that operating rates are only 77%. There is plenty of slack capacity and no great need for new plant and equipment.

The market has clearly responded favorably to the election of Donald Trump last November. Aside from his pro-growth agenda, he promised to bring a more business-friendly attitude to Washington. His failure to get any of his major initiatives passed through Congress has been a disappointment and one would think the market’s response to that would be negative. What has neutralized the lack of progress on his agenda is the better current performance of the economy itself, notwithstanding any boosts it might get from his agenda of tax reform, decreased regulation and infrastructure spending. Real growth in the U.S. is headed toward 3% and the economy seems to be gaining momentum rather than slowing down, as it usually does in the second half of a business cycle. Moreover, there is reasonable prospect of deregulation at the administrative level.

While the Trump administration appears to be off to a slow start on legislation, most investors believe that there will be a reduction in corporate taxes by the end of 2017 or early next year and other aspects of Trump’s agenda will be passed in 2018. The recent deal to lift the debt ceiling and temporarily keep the country running was viewed as an indication of Trump’s flexibility, his negotiating skill and his willingness to act in opposition to some key Republican leaders to get a necessary piece of legislation done. The question is whether his strained relationship with important members of his party will make it difficult to get other parts of his program implemented. My guess is that we will definitely see a tax cut, but probably not broad tax reform; continued deregulation, particularly in industries like energy and finance; and infrastructure spending, stimulated by rebuilding as a result of Harvey and Irma. Most of this, however, will happen next year.

The hurricanes pushed North Korea off the front pages of newspapers across the country, but the market had begun to scale back its fear of Kim Jong-Un even before the storms. There may be two reasons for that. The first is that Kim has achieved his objective of getting North Korea viewed as an important country at least militarily. He will never give up his nuclear arsenal, since he knows it will discourage any outside threats. The second is that while Kim is impetuous, unpredictable, and even homicidal, he is not, as Tom Friedman has pointed out, suicidal. He demonstrated this when he threatened to hurl an intercontinental ballistic missile at Guam and then backed off, sending the missile into the northern Pacific Ocean instead. He knows that any unprovoked attack by North Korea involving the loss of life of innocent people would cause China to abandon Kim and be met with instant and massive U.S. retaliation, endangering the North Korean population and his family’s regime. Sanctions have had an impact on his already weak economy. An increase in sanctions, particularly by China, could be devastating, but that is not likely to happen, so we will have to hope that Kim’s truculence quiets down on its own. Containment is the most likely U.S. policy. If I am right and he has achieved the respect he seeks, perhaps that will happen, although the harsh rhetoric and threats are likely to continue.

There is always the risk of a policy mistake out of Washington that negatively changes the mood of the market. The departure of Steve Bannon as the administration’s chief strategist and the arrival of John Kelly as chief of staff have been viewed positively by investors. The chance of a poorly reasoned decision on trade or foreign policy has diminished. The two potential trouble spots on trade are China and NAFTA. Trump continues to believe that China is dealing in an unfair way with the United States and he wants to change that. He must realize, however, that China is a key supplier of component parts for many items assembled in America as well as a producer of goods no longer made here. He must view the country as a trading partner and not an adversary. While he can fairly be tough on intellectual property and tariffs, he should not let the relationship become hostile. With regard to NAFTA, the agreement can be improved through modification, but scrapping it would be unwise. I believe that’s the position that Wilbur Ross, Steve Mnuchin and Gary Cohn will take, and they are the key players here. Trump has shown a willingness to shift toward modification rather than termination in the Iran deal.

Many investors are concerned about an increase in inflation in view of the tight labor market that has resulted from the low level of unemployment and the monetary expansion that began in 2008 and continued until last year. As Milton Friedman famously said, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.” Friedman is no longer around to answer to his fellow economists as to why his pronouncement is no longer accurate. The combination of globalization and technology have worked together to keep inflation low. The highly respected and closely watched Phillips curve no longer has predictive value. It would argue that inflation should be moving up because of low unemployment. We had a similar circumstance in 1999 when the Federal Reserve decided to raise interest rates by a quarter point in spite of a lack of evidence that inflation was rising. They kept raising rates and by May of 2000 the federal funds rate was 6½%, up from 4¾% in June 1999, thereby contributing to the bear market we experienced at that time when the technology bubble burst. They are not likely to make the same mistake again.

The Bank Credit Analyst (BCA) has identified some other indicators that could provide an early warning on inflation. They include personal consumption expenditures, the producer price index for finished goods, the Institute for Supply Management Manufacturing Prices Paid and the Corporate Prices Paid deflator. Only the finished goods indicator looks troubling now. In that connection, BCA also has found money velocity a useful indicator of future inflation, and this looks like it could be signaling a problem at some point in the near future.

Although the hurricanes may have put the Fed on hold in terms of increasing interest rates, we will likely see some hikes next year. The current yield of intermediate-term Treasurys will also likely rise. The combination of a better economy, a rising stock market and a tighter Fed should mean a stronger dollar, but that is not how the currency has performed this year. There are, however, some benefits from the dollar’s decline. The European Central Bank is less likely to taper, American exports are attractively priced and foreign earnings of U.S. companies are worth more. I expect the dollar to remain around present levels or strengthen against the euro over the near term and not be a factor in the performance of the equity market.

Still, there are plenty of other issues to worry about. There could be a jam in the Exchange Traded Funds market as a flood of investors rush to get out of specific ETFs at the same time. There are loans outstanding made by marginal companies that would have difficulty paying principal or even interest in a business downturn. The Chinese shadow banking system has a number of non-performing loans on its balance sheet. As long as the Chinese economy is thriving, these may not be a problem but they do represent a potential risk. The U.S. economy is doing well now, but the prosperity is very unevenly distributed. Large areas of the mid-west are struggling and we all should be on the lookout for signs that the economic cycle is topping.

There is always much to worry about and the investment business requires money managers to weigh the variables and make a judgment. Based on my analysis, I think we will have a favorable environment for equities at least until 2019. I will, however, be watchful for changes in the conditions that brought me to that conclusion.