by Lance Roberts, Clarity Financial

An interesting thing happened on the way to World Domination, uhh, I mean “Stability” – the data quit cooperating with the Federal Reserve’s carefully devised plan.

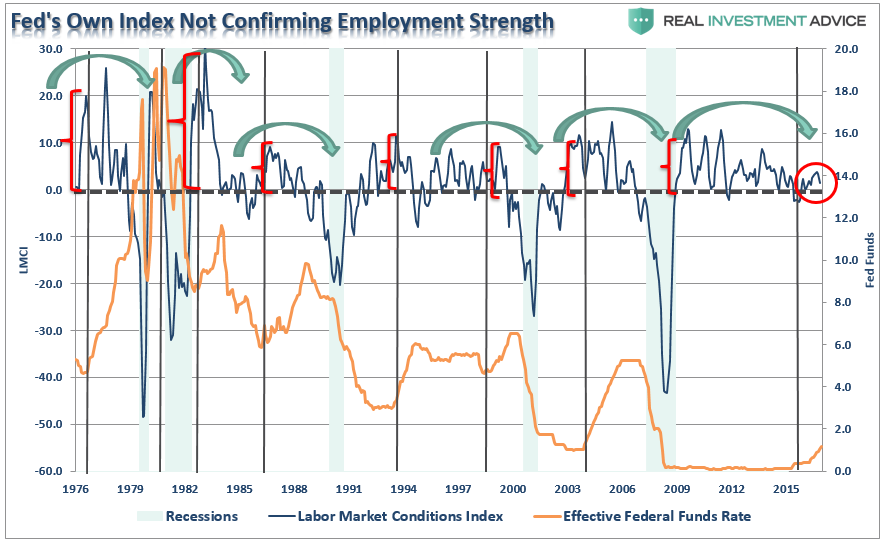

Just recently the Federal Reserve quit updating their carefully constructed “Labor Market Conditions Index” which failed to support their ongoing claims of improving employment conditions. The chart below is the last iteration before it was discontinued which showed a clear deterioration in underlying strength.

But to add insult to injury, inflationary pressures have not resurfaced as anticipated despite years of ultra-low interest rates and a flood of liquidity into the financial system. This has now led the Fed to start considering whether their cornerstone inflation model still works. As Bloomberg noted recently:

“Federal Reserve officials are looking under the hood of their most basic inflation models and starting to ask if something is wrong.

Minutes from the July 25-26 Federal Open Market Committee meeting showed a revealing debate over why the economy isn’t producing more inflation in a time of easy financial conditions, tight labor markets and solid economic growth.

The central bank has missed its 2 percent price goal for most of the past five years. Still, a majority of FOMC participants favor further rate increases. The July minutes showed an intensifying debate over whether that is the right policy response.”

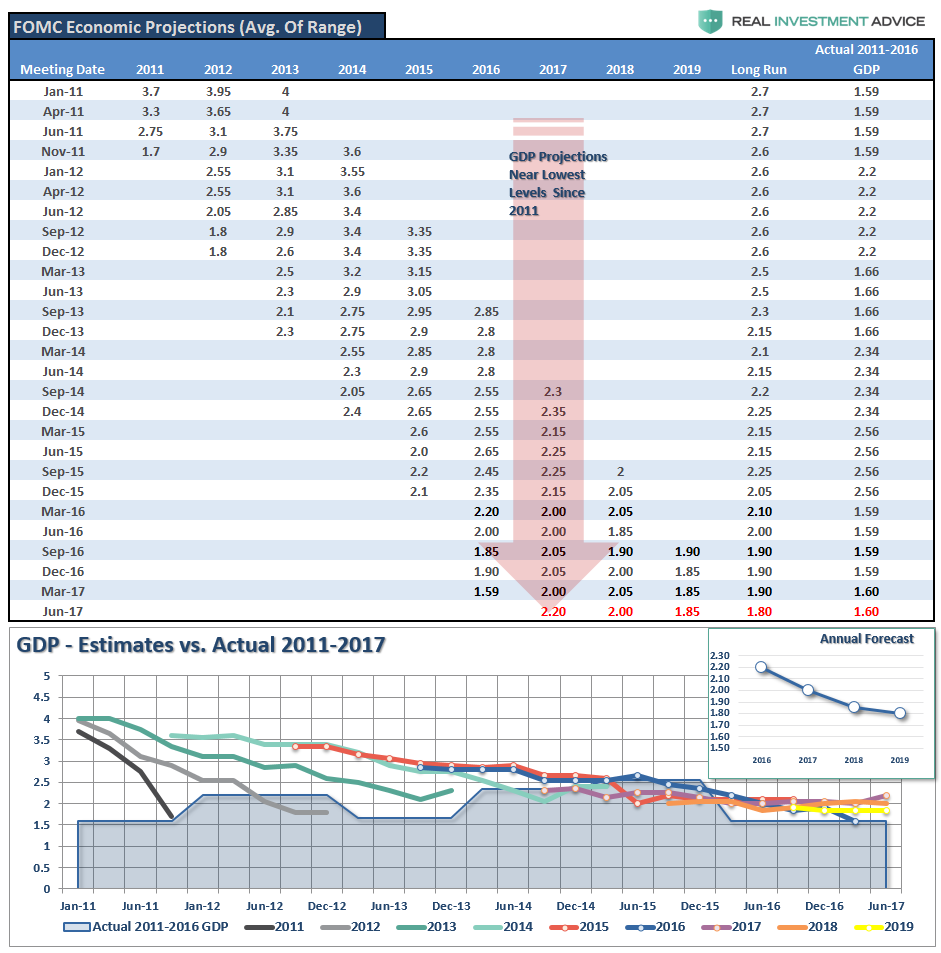

Of course, nowhere is the Fed’s inability to forecast efficiently than in their own published forecast they began producing in 2011 to be more “transparent” with the financial markets. The results have been spectacularly disastrous.

However, despite the clear evidence that economic growth is hardly running at levels that would be considered “strong” by any measure, the Fed has decided the best path forward to continue “tightening” monetary policy. This is ironic considering the ENTIRE PURPOSE of TIGHTENING monetary policy is to SLOW economic growth to keep inflationary pressures at bay.

The disconnect between Fed policy and the economy is nothing new. This was a point recently made by Neal Kashkari:

“At the same time the unemployment rate was dropping, core inflation was also dropping, and inflation expectations remained flat to slightly down at very low levels. We don’t yet know if that drop in core inflation is transitory. In short, the economy is sending mixed signals: a tight labor market and weakening inflation.”

Kashkari is right in worrying that the Fed is placing too much faith on the Phillips Curve which predicts a tighter reverse relationship between the unemployment rate and inflation than has actually been seen in recent years. This is particularly the case given the problems with the underlying U-3 employment rate calculation as discussed just recently. To wit:

“Has there been ‘job creation’ since the last recession? Absolutely.

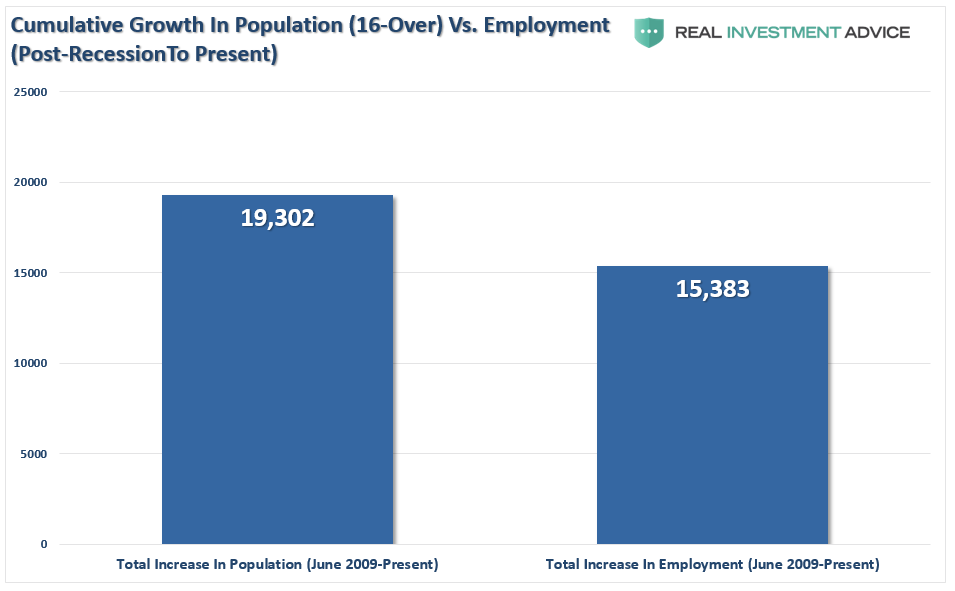

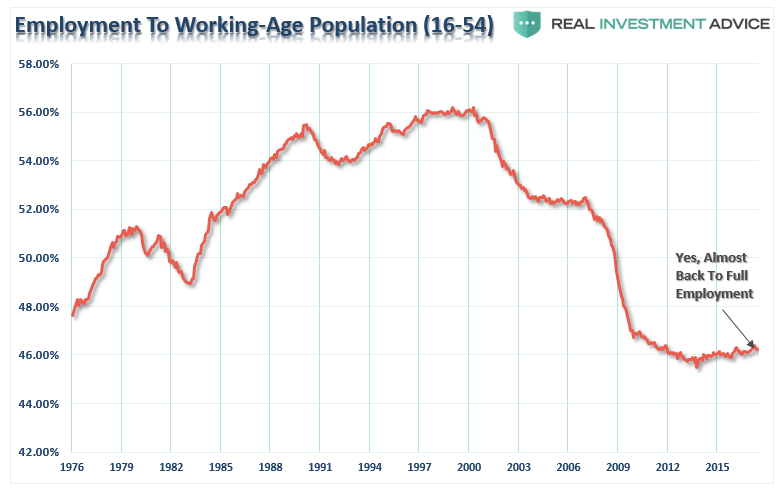

If you take a look at the actual number of those “counted” as employed, that number has risen from the recessionary trough. Unfortunately, employment remains far below the long-term historical trend that would suggest healthy levels of economic growth. Currently, the deviation from the long-term trend is the widest on record and has made NO improvement since the recessionary lows.

However, as it relates to economic growth, what is always overlooked is the number of new entrants into the working-age population each month.”

The problem for the Fed in making the decision to discontinue their own Labor Market Conditions Index, which is likely providing a more accurate picture of the real conditions, is being forced to remain tied to an outdated U-3 employment index. As noted recently by Morningside Hill:

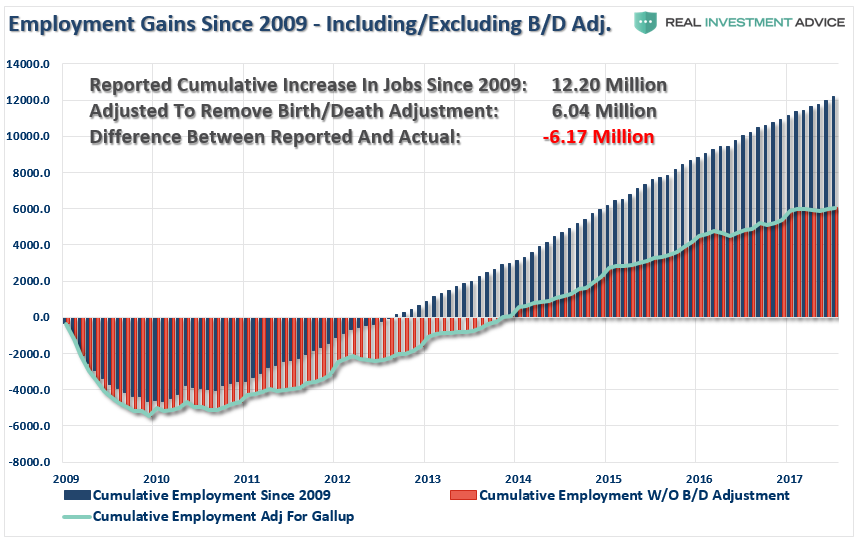

“There is sufficient evidence to suggest the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) calculation method has been systemically overstating the number of jobs created, especially in the current economic cycle. Furthermore, the BLS has failed to account for the rise in part-time and contractual work arrangements, while all evidence points to a significant and rapid increase in the so-called contingent workforce as full-time jobs are being replaced by part-time positions, resulting in double and triple counting of jobs via the Establishment Survey.

Lastly, a full 93% of the new jobs reported since 2008 and 40% of the jobs in 2016 alone were added through the business birth and death model – a highly controversial model which is not supported by the data. On the contrary, all data on establishment births and deaths point to an ongoing decrease in entrepreneurship.”

This last point was something I have addressed many times previously, the chart below shows the actual employment roles in the U.S. when stripping out the Birth/Death Adjustment model. With such a large overstatement of actual employment, the flawed model does support the idea of a tight labor market.

Unfortunately, despite arguments to the contrary, there is little support for why the bulk of Americans that should be working, simply aren’t.

This is where Neal goes on to identify the prevalent risk for the Fed:

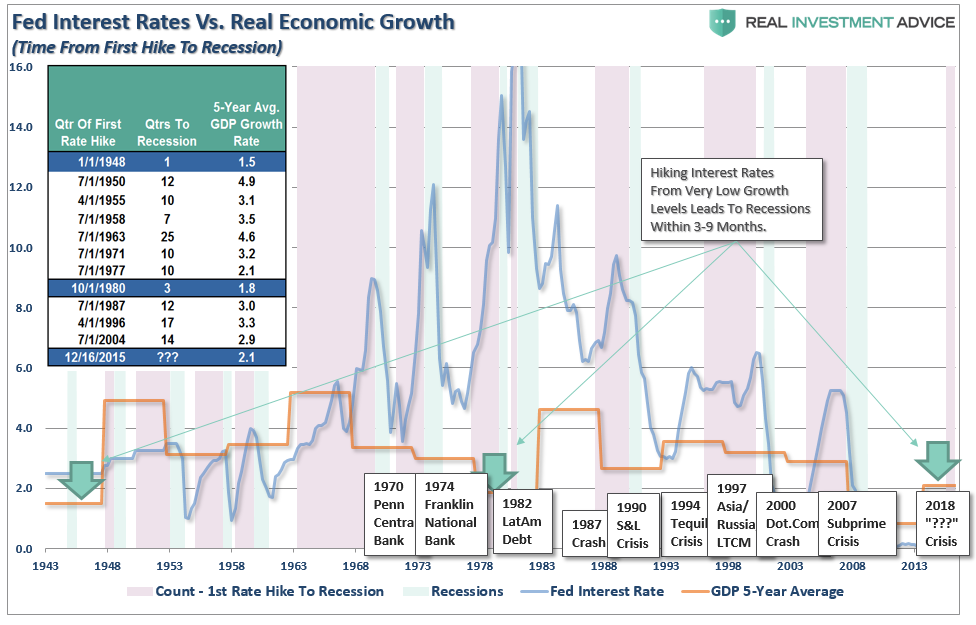

“In the 1970s, that faith led the Fed to keep rates too low, leading to very high inflation. Today, that same faith may be leading the Committee to repeatedly (and erroneously) forecast increasing inflation, resulting in us raising rates too quickly and continuing to undershoot our inflation target.”

Let me be clear.

The Fed is not actually concerned with employment or price stability.

They are vastly more concerned with keeping the financial markets running smoothly. Their goal, which was clearly stated back in 2010, was simply to force individuals to get their money out of “savings accounts” and put it to work either through consumption or investment. They enforced that mandate with a “club” of zero percent interest rates.

The problem for them now, is trying to reign that back in before the next recession. This puts the Federal Reserve in a very difficult position with very few options. While increasing interest rates may not “initially” impact asset prices or the economy, it is a far different story to suggest that they won’t.

Unfortunately, what the Federal Reserve is quickly realizing is they have become trapped by their own “data-dependent” analysis. Despite ongoing commentary of improving labor markets and economic growth, their own indicators have continued to suggest something very different.

Now they are simply considering abandoning those tools.

Is this a sign they have lost control of monetary policy?

Probably.

Will this ultimately lead to a policy misstep the disrupts the financial, and most importantly, the credit markets?

Definitely.

Why do I say that? Because there have been absolutely ZERO times in history that the Federal Reserve has begun an interest-rate hiking campaign that has not eventually led to a negative outcome.

While the Federal Reserve clearly should not raise rates further in the current environment, it is clear they will remain on their current path. This is because, I believe, the Fed understands that economic cycles do not last forever, and we are closer to the next recession than not. While raising rates will accelerate a potential recession and a significant market correction, from the Fed’s perspective it might be the “lesser of two evils.” Being caught near the “zero bound” at the onset of a recession leaves few options for the Federal Reserve to stabilize an economic decline.

In other words, they already realize they are screwed.

Copyright © Clarity Financial