With equity valuations at elevated levels, subdued economic growth due to changing demographics and stubbornly low productivity gains, as well as a bleak outlook for fixed income, advisors are challenged to rethink foundational portfolio elements of investor portfolios—which means seeking out strategies that bolster the core going forward.

In investing, the “core” has traditionally consisted of developed market equities and investment grade debt. Increasingly over the last decade, investors—both retail and institutional—have introduced a growing number of diversifying elements to that core, including commodities, floating rate and high yield debt, emerging market assets, and hedge fund strategies, to name a few. Those asset groups have, in portfolio construction lingo, been termed “satellite” allocations.

But not all satellites are distinctly different from core assets. Of all of the satellite strategies, the one that most closely resembles the foundational components of a typical portfolio is Long/Short Equity. It is after all a strategy, not an asset class, which invests in equities, and more often than not, does so with net exposure well below 100%, and that ends up looking quite similar to a combination of equities and cash or bonds.

As an aside, for those new to Long/Short Equity, you may be wondering at a conceptual level why you should even consider investing in such a strategy. Our response is that portfolio managers and analysts, whether discretionary or quantitative, expend tremendous effort in identifying securities with higher expected risk-adjusted returns than the market at large. Through these efforts, they likewise come across securities with lower expected risk-adjusted return profiles. Long-only managers utilize such information primarily to avoid stocks with poor outlooks. Long/short managers, on the other hand, are afforded greater flexibility to fully express their views on all securities that they research, improving investment efficiency. Greater efficiency is achieved because more of the information uncovered during the research process is acted upon. A security identified as having superior characteristics is purchased, a security with a poor outlook is shorted, and a security with a market-like payoff is put aside until such time that either valuation or fundamentals turn it into a higher conviction long or short position.

By exploiting a larger opportunity set while reducing market exposure, Long/Short Equity has historically generated compelling risk-adjusted returns.

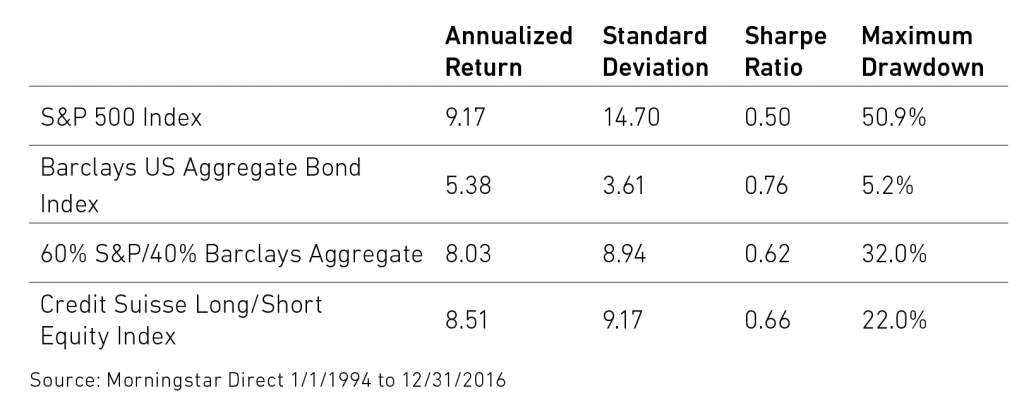

But let’s continue with the idea that Long/Short Equity has characteristics similar to core assets. A correlation analysis of the return streams for equities, as represented by the S&P 500 Index, and Long/Short Equity strategies, proxied by the Credit Suisse Long/Short Equity Index, reveals that from January 1994 through December 2016, equities and Long/Short Equity strategies exhibited a correlation of about 0.7. As alluded to earlier, this fairly high correlation is to be expected given that Long/Short Equity strategies derive the bulk of their return from equity beta, albeit in a lessened form from long-only constrained portfolios. Further, consider the following risk and return characteristics.

Long/Short Equity strategies have come close to matching the performance of equities with essentially the same level of volatility as a 60/40 stock/bond portfolio, and with better downside protection. (This over a time period when the yield on the 10-Year Treasury went from 5.75% to 2.45%, which was unquestionably beneficial to the performance of investment grade debt.)

Historical returns of Long/Short Equity strategies have been comparable to those of long-only strategies, with half of the risk.

To be fair, point-in-time statistics can hide a lot, both good and bad. There have been many periods over the last 22 years when investors would have been better off in a 60/40 portfolio, most notably in 2011 when the Credit Suisse Long/Short Equity Index fell by 7.3% and a 60/40 portfolio returned almost 5%.

Rolling 1-Year Returns

But here’s the question. Could even the most astute professional investor determine in advance when such time periods will be more conducive to a 60/40 core than for a Long/Short Equity strategy? We are not stating that Long/Short Equity should completely replace the traditional stock/bond core, but rather it could replace a portion of that core and potentially improve overall performance, through an increased number of alpha sources, while dampening volatility, among other things.

Of course in order to implement such a change, one must be able to identify a good Long/Short Equity fund that is open to new investors and isn’t bloated with assets. Due diligence on Long/Short Equity managers is indeed more complex, and size is undeniably the enemy of all investment strategies (i.e., the more assets raised, the harder it is to put those assets to work without incrementally lowering the return potential of the portfolio).

On the question of how to evaluate Long/Short Equity managers, we offer a few suggestions. For one, in order to properly analyze any investment strategy, it’s imperative to identify the risk factors embedded in the portfolio. All returns come from bearing risk in some form, so what risks are prevalent within Long/Short Equity portfolios? At the most basic level of course, investors in Long/Short Equity strategies take on equity risk, and therefore garner the lion’s share of their return from the equity risk premium. In addition, investors may be compensated for exposure to other risk premia, such as size, value, or momentum. With the proliferation of cheap passive strategies that provide exposure to these same factors, investors should not pay up for these exposures, and should not mistake them for sources of “alpha”, unless of course the manager can demonstrate skill in varying exposure to these factors in a consistent manner.

Additionally, it is important to measure the manager’s ability to add value through stock selection on both the long and short books. If a manager cannot generate alpha on the long book, there is no question that investors should look elsewhere. But what about the short book? Our answer is that it depends. If the short book is intended to be a source of alpha, then the short book should be held to the same standard. If however, the short book merely serves as a hedge, then the question turns to whether or not the manager can add value by varying the net exposure over time through the use of its hedges. A manager who maintains a relatively static hedge simply to keep equity beta in line with other long/short funds isn’t adding any value, and investors shouldn’t be paying for this “service”.

Manager selection aside, it is our belief that the need for long/short strategies may be greater today than it’s been in decades due to the market environment in which we find ourselves. The starting point, in terms of valuation and fundamentals, is highly predictive of future returns, even if it is silent as to timing. And today’s starting point isn’t all that promising, as we find ourselves sitting on lofty valuations by historical standards, with a Shiller Cyclically Adjusted PE Ratio of about 29 times earnings versus a long term average of 16.74, and with interest rates now moving away from their all-time lows, as measured by the 10-year Treasury.

Shiller Cyclically Adjusted P/E Ratio

While equity valuations can and do reside far from their means for extended periods, which adds significant uncertainty to expected returns, bond valuations expressed in current yields do tend to be more predictive of near-term returns for investment grade debt, a key component of the typical core portfolio. With that in mind, let’s explore the potential pathways for rates.

What if rates remain relatively flat for the next few years? Over the medium term, say 5 years or so, the best predictor of bond market returns, as measured by the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index (the “Aggregate”), is the yield at the time of investment, which isn’t surprising given that the duration of the Index is about 6 years. Currently, the yield on the Aggregate is about 2.6%. Further, our estimate of future inflation, which is based on a simple model that combines the inflation forecast from the Philadelphia Fed’s Survey of Professional Forecasters and the implied breakeven rate of inflation between nominal Treasuries and TIPS (adjusted for the liquidity premium), suggests that inflation will run around 2.4% over the next 5 years.

Therefore, even without a much feared rise in interest rates, the best investors can reasonably hope for from their U.S. investment grade bond holdings over the next five years, is a return of very close to zero on a real basis.

Of course, the math will likely be worse if rates rise, although reality might not be as bad as many investors believe. In a rising rate environment, investors can recycle coupons into higher yielding assets, which can offset some of the price declines suffered by existing holdings. Having said that, in a prolonged environment of increasing rates (and presumably, increasing inflation), things do get ugly.

Long term corporate bonds and long term government bonds experienced four consecutive decades of negative real rates of return beginning in the 1940s. Forty years is an entire investment horizon for the typical investor, who begins saving at age 25 and retires at age 65. While it would seem highly unlikely that history would repeat in such a way, investors at least need to be cognizant of the fact that it isn’t outside of the realm of possibility.

And what if rates continue to fall? Well, if that is the case, we will undoubtedly be knee deep in a worsening economic quagmire, and investors could still do well in investment grade debt for a while longer, as their equities falter.

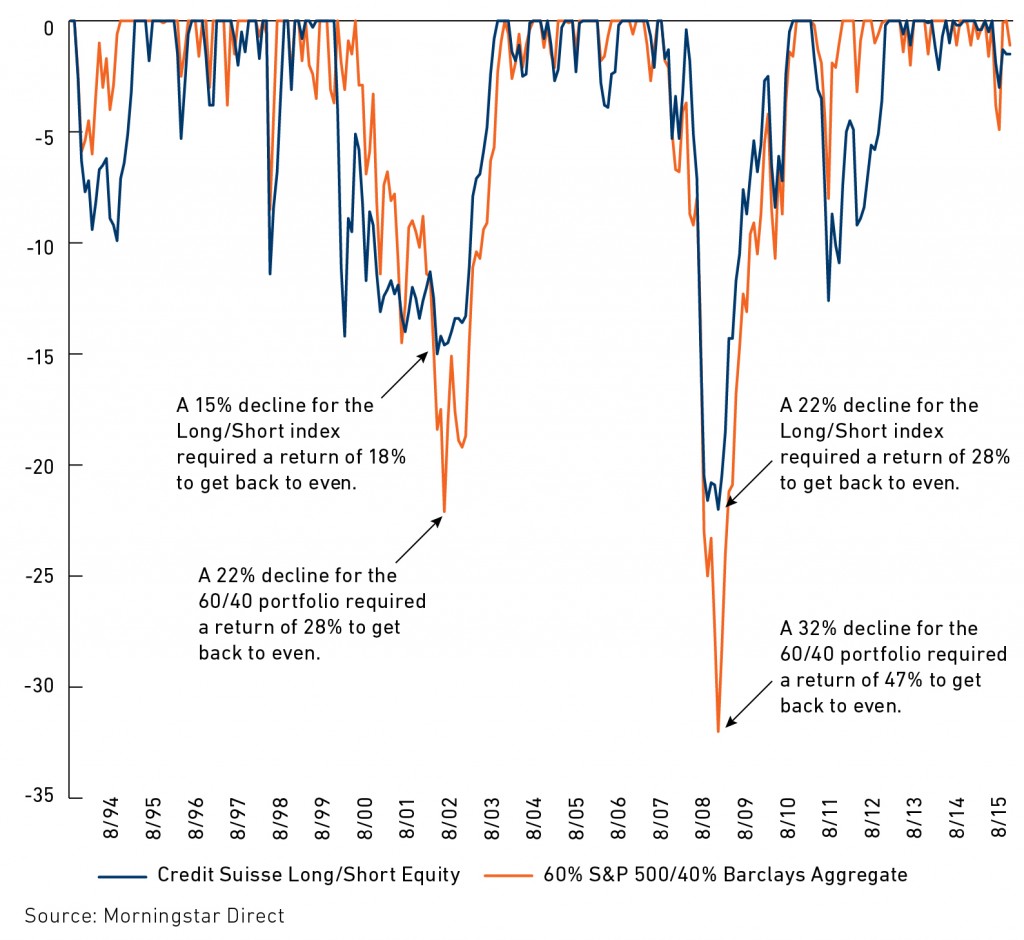

Importantly, most retail investors, as opposed to institutions investing into perpetuity, don’t have the luxury to wait to earn the “average” returns offered by the long term. With only a few decades over which to save and invest for retirement, a prolonged period of low real returns can be quite detrimental, as that reduces the time over which compounding can work its magic. And in these low return environments, the solution cannot be to throw caution to the wind, increase risk and hope for the best, as the math of a big loss can be very difficult from which to recover.

Rolling Drawdowns & The Math of Big Loss

Ultimately, we believe Long/Short Equity should replace, at least in part, core assets rather than being lumped in with the amorphous and heterogeneous “alternatives” bucket, because of the dangers inherent in the latter approach. Too often, asset allocation and manager selection are conducted independently, rather than in an integrated and iterative fashion. And if, for example, an investor determines that the optimal asset allocation is 50% equities, 35% bonds and 15% “alternatives”, and then proceeds to fill the alternatives allocation with Long/Short Equity managers, the unintended result will be a portfolio with far more equity than originally desired. The risk/return profile of such a portfolio will be entirely different from one where the “alternatives” bucket delivers truly uncorrelated return streams, as would be the case with managed futures or convertible arbitrage, for example.

Long/Short Equity should be thought of as a core position, not as a minor ‘alternative’ allocation floating out amongst the satellites. Over multiple market cycles (including two major crashes), Long/Short Equity strategies have outperformed the 60/40 core on a risk-adjusted basis, and for that reason, coupled with a market environment that portends low future returns, Long/Short Equity strategies belong within the core.

Copyright © 361 Capital