MARKET ETHOS: Best to be Unloved

by Craig Basinger, CFA, Connected Wealth, RichardsonGMP

Behavioral Finance combines behavioral and cognitive psychology theory with conventional economics and finance.

Essentially it attempts to account or add the “human” element into understanding how the markets behave. While still a relative new area, it has garnered a great amount of attention. The most common aspects of this discipline are behavioral biases, such as loss aversion, framing, overconfidence, anchoring, recency, overreaction, etc. Many publications are devoted to helping investors understanding these biases to avoid their negative impact on performance.

At Connected Wealth we are taking this one step further. The team is currently researching not only the various biases in the real world but working on investment strategies that take advantage of these biases. In the coming months we will be publishing on various aspects of this work and we welcome any feedback.

Everyone likes a good analyst upgrade on a stock they already own. Depending on the analyst, size of following, size of firm, share prices certainly react to these changes of opinion. Think about this analyst rating change for a minute. Nothing has actually changed for the company, their business is the same as it was the day before the rating change, their risks are the same, even their cash flows are not impacted. Yet, overnight the value of their business just became a few percentage points higher or lower.

It did because the rating change elicits a behaviour of investors to buy or sell said company. Investing is fraught with uncertainty, but hearing someone (the analyst, legitimately an expert) likes something more, inclines the investor to like it more.

We, as humans, are predisposed in a world that has risk, to stick together. It is how we survived when there was actual physical dangers from other species, how we endured during conflicts with other groups of people.

Yes, we are referring to investor behaviour from an analyst rating change as herd like behaviour. But we have also learned over the years that money is more often made by not following the herd. In fact, let’s see if we can support this view.

A look at analyst ratings

We ran an analysis over the past ten years for the TSX and S&P 500, grouping companies based on how much they were loved or unloved by the analyst community. The calculation was based on the number of buy ratings on a given company as a percentage of the total number of analysts following a company. So if it was 20%, that would mean 20% of analysts have a buy with the remaining analysts at hold or sell. From 2007 to 2017, we grouped companies each month into five groups ranging from the most loved by analysts to the least loved. Then performance was calculated going forward until the next rebalancing.

We ran an analysis over the past ten years for the TSX and S&P 500, grouping companies based on how much they were loved or unloved by the analyst community. The calculation was based on the number of buy ratings on a given company as a percentage of the total number of analysts following a company. So if it was 20%, that would mean 20% of analysts have a buy with the remaining analysts at hold or sell. From 2007 to 2017, we grouped companies each month into five groups ranging from the most loved by analysts to the least loved. Then performance was calculated going forward until the next rebalancing.

As the charts on page one shows, during this period and more so in Canada, the companies with the least percentage of buy ratings (unloved) outperformed the companies with the most buy ratings (loved). This does seem counter intuitive, as it implied there are greater returns available in buying companies with fewer buy ratings. We included the least loved and 2nd least loved quintiles in the S&P 500. The trend in both Canada and the U.S. is not constant as there were periods when more loved companies did outperform, but the prevailing trend over the past decade that includes a full market cycle does appear to favour those companies the analysts like the least.

As the charts on page one shows, during this period and more so in Canada, the companies with the least percentage of buy ratings (unloved) outperformed the companies with the most buy ratings (loved). This does seem counter intuitive, as it implied there are greater returns available in buying companies with fewer buy ratings. We included the least loved and 2nd least loved quintiles in the S&P 500. The trend in both Canada and the U.S. is not constant as there were periods when more loved companies did outperform, but the prevailing trend over the past decade that includes a full market cycle does appear to favour those companies the analysts like the least.

Why

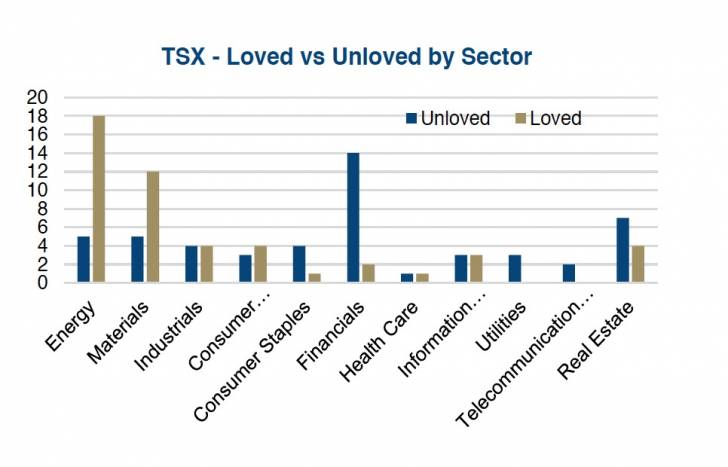

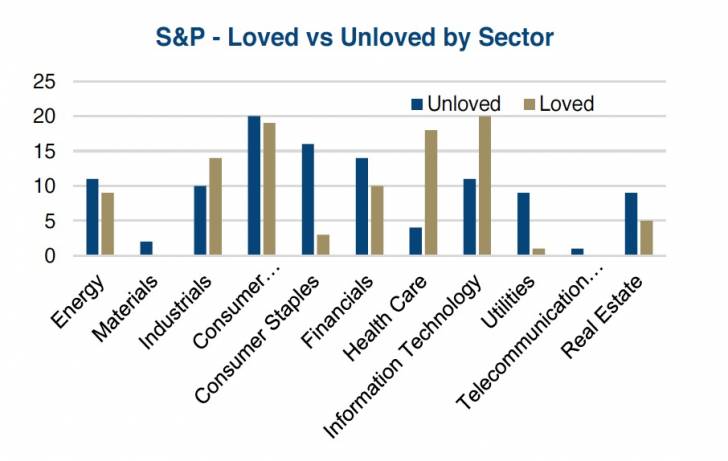

This of course is the hard part, developing a useable and defendable theory for this trend. First we looked at sector composition between the loved and unloved companies. This is a snap shot as of the latest period. In Canada, there is a lot of analyst love for Energy and Materials while Financials are the least loved. Conversely in the U.S., there is more love for Health Care and Technology with Utilities and Staples as the least loved. The least loved in both counties tend to be more interest rate sensitive relative to the most loved, so perhaps there is an interest rate factor at play. Yields have been largely going down over the past ten years which would favour those least loved sectors on a relative basis.

There also could be a reversion factor or even a cycle to analyst recommendations (chart). At the extreme, if there are no buy recommendations, the next change pretty much has to be an upgrade as there are no more downgrades left. Alternatively, what if there was an analyst cycle. A company performing well is loved by analysts. Then there is a miss but it is still loved as markets view it as a buying opportunity.

There also could be a reversion factor or even a cycle to analyst recommendations (chart). At the extreme, if there are no buy recommendations, the next change pretty much has to be an upgrade as there are no more downgrades left. Alternatively, what if there was an analyst cycle. A company performing well is loved by analysts. Then there is a miss but it is still loved as markets view it as a buying opportunity.

More misses and then the downgrades start mounting as the company enters the unloved zone. At some point the company turns around, perhaps due to business model or even economic cycle changes. A few upgrades lead the pack and then more pile on. So is there money to be made finding companies that were in the unloved zone but start to see upgrades? Those first few upgrades could be the better analysts seeing a turnaround in the company or attractive valuations, upgrading ahead of the pack.

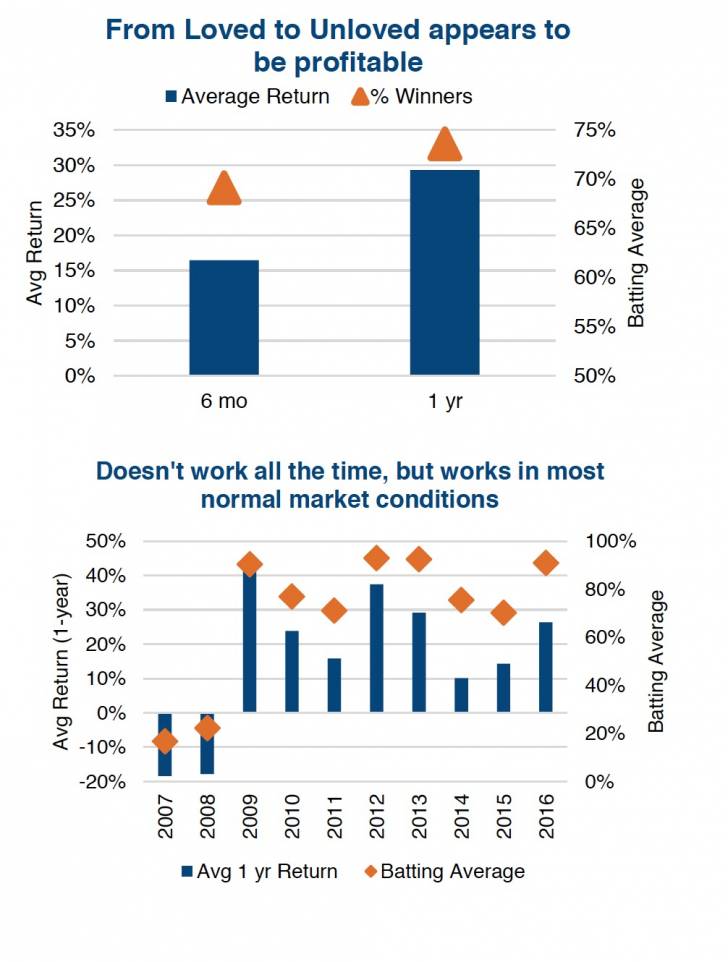

Over the past ten years we looked for any company that was unloved for three months or longer. Unloved was defined as having less than 30% buy recommendation. We then measured the one year and six month forward performance if the buy recommendations moved above 30%. In other words, they moved from being unloved to, well, less unloved. The hope is the upgrades are early with more upgrades to come.

For the S&P 500, over ten years, there were about 270 instances that matched our criteria of moving from a long period of unloved to being less unloved. The average six month performance was +16% and +29% for a year. The success rate was 73% of the time the share price was higher a year out. That is reasonable. Even better, the average gain was 49% compared to an average loss on those that went down of -26% for a year.

For the S&P 500, over ten years, there were about 270 instances that matched our criteria of moving from a long period of unloved to being less unloved. The average six month performance was +16% and +29% for a year. The success rate was 73% of the time the share price was higher a year out. That is reasonable. Even better, the average gain was 49% compared to an average loss on those that went down of -26% for a year.

We also looked at the results in each calendar year. No doubt this is not a solution for bear markets, given the data from 2007 and 2008. Yet in normal markets, the strategy does appear to have some validity.

Investment Implications

It may be useful to look for companies that have been unloved by analysts for an extended period of time that start to see upgrades. Perhaps these first upgrades are the more forward looking analysts that see a turnaround. Or perhaps a simple reversion to the mean bodes well for the share price after being hated for so long. Either way, it does look profitable to look at unloved companies once in a while.

*****

Charts are sourced to Bloomberg unless otherwise noted.

This material is provided for general information and is not to be construed as an offer or solicitation for the sale or purchase of securities mentioned herein. Past performance may not be repeated. Every effort has been made to compile this material from reliable sources however no warranty can be made as to its accuracy or completeness. Before acting on any of the above, please seek individual financial advice based on your personal circumstances. However, neither the author nor Richardson GMP Limited makes any representation or warranty, expressed or implied, in respect thereof, or takes any responsibility for any errors or omissions which may be contained herein or accepts any liability whatsoever for any loss arising from any use or reliance on this report or its contents. Richardson GMP Limited is a member of Canadian Investor Protection Fund. Richardson is a trade-mark of James Richardson & Sons, Limited. GMP is a registered trade-mark of GMP Securities L.P. Both used under license by Richardson GMP Limited.

Copyright © Connected Wealth, RichardsonGMP