How the wealthy build their fortunes

by Jeff Hyrich, Vice President and Portfolio Manager, Trimark Investments, Invesco Canada

If you were to look at the annual lists of the wealthiest people in Canada, focusing on those who got there through their own efforts rather than inheritance, you may find a few key similarities among the wealthiest.

They usually own good businesses that generate lots of free cash, they tend to own their business for long periods of time (letting their wealth compound) and they only need to own a single business rather than many different businesses. We try to run Trimark Global Endeavour Fund the same way – by buying quality stocks at reasonable valuations, owning them for the long term and not over-diversifying.

In this post, I’m going to outline our process and give you some of the highlights around how the discipline works in the real world. My hope is that a mix of discipline and data will give you a clear sense of how we manage the Fund and what you can expect from us in the future.

Driven by discipline

Our long-term investment results are driven by the investment process, or discipline, that we adhere to on a daily basis (and that hasn’t changed much since I started on the Fund on October 1, 2001). The goal is to find and own investments in what we perceive to be high-quality growth companies that have strong balance sheets and capable management teams and that are available for purchase at reasonable valuations. We supplement this by running a concentrated portfolio and typically holding our investments for a long time period.

At year-end 2016, the Fund owned 36 equity holdings, with approximately 65% of the fund’s assets concentrated in the top 20 holdings. In contrast, the 10 largest global equity funds in Canada, each own, on average, 94 stocks – almost triple the number of our holdings. Our turnover rate for the past three years has averaged 11%, compared with a 43% turnover rate for our top-10 peers. Turnover means how much buying and selling a mutual fund manager does in a year. We hold our stocks, on average, for nine years compared with less than 2.5 years for the top 10 global equity funds.

We purchase approximately four new ideas per year, compared with about 40 new names per year for our peers – about 10 times more than us. Think about that for a minute – buying fewer names enables us to do more in depth research and be more selective and discerning about what gets into our portfolio.1

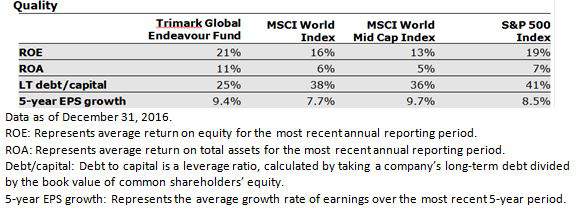

Looking at returns on capital – both levered [i.e., return on equity (ROE)] and unlevered [i.e., return on assets (ROA)], the companies in the Fund have not only generated higher returns on their capital bases, but also did so with substantially less financial leverage or debt. I believe in the saying, “It’s hard to go bankrupt if you have no debt.”

In terms of growth, the Fund’s holdings have historically grown at similar or faster rates than the various indices.

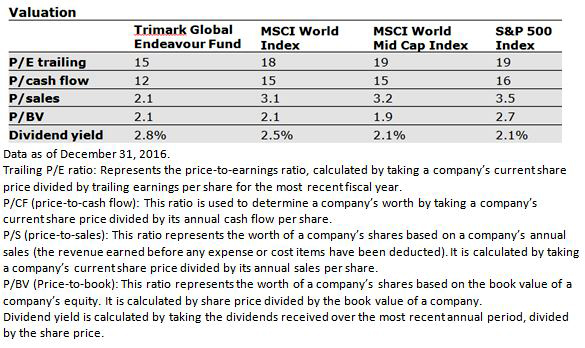

Looking at the valuations below, you’ll see that the companies in the Fund are trading at a more than 20% average discount to the indices2, irrespective of the quality elements highlighted above. And you could make an argument that the companies are attractive at similar valuation levels, or even at a premium to the various indices.

That’s what stock-picking and portfolio construction are all about. We have gone around the world, looking in all its “nooks and crannies” to identify and invest in quality stocks that we feel are undervalued. It’s not easy, and we prefer to fish deep and fish alone to find inefficiency and advantage.

Managing risk

Another important metric is risk management. Unlike industry standards, we do not view risk as volatility, which means how much a company’s stock price moves up and down every day. We consider risk more as a permanent loss or impairment of our capital – losing money with no chance or hope of making it back.

I’ve already touched on a couple of ways we manage risk: by owning high-quality companies that are competitively positioned, owning companies with low amounts of debt and only buying stocks when we feel they are undervalued and there exists a “safety margin.”

What is a safety margin? If we think the value of a business is, say, $100 per share, we’re going to try and purchase shares at a discounted price of, say, $60. Our thinking is that if something bad happens, such as a recession or increased competition, we’ll have purchased the stock at enough of a discount that even if the value of the business decreases from $100 to $70, we still bought into the company cheaply enough that we should only incur minimal losses. It doesn’t always happen this way and we’ve made our share of mistakes, but it’s what we strive for. This discount or margin of safety was evident in the discounted valuations shown above.

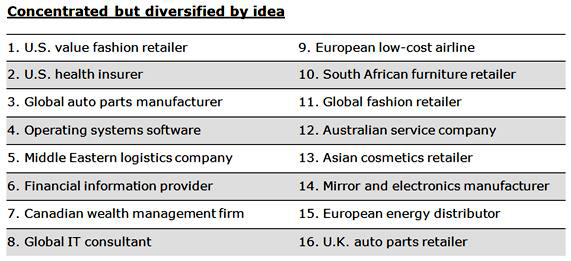

Another way we think about risk is to be diversified across investments. Some people ask us how we can be diversified when we run a concentrated portfolio. Our response is that we try not to make the same investment multiple times. We try to own one of this and one of that, and not five of the same kind of investments.

Contrast this to the typical Canadian equity mutual fund and you’ll probably see that they own five Canadian banks in their top 10 holdings. Why would they do that? What happens if, say, there’s a real estate crash in housing, like we saw in the U.S. from 2006 to 2009? Won’t all these Canadian banks be exposed to the exact same issues? Is this diversification or is this a fund manager behaving like a closet index fund while still charging high fees for “active management”?

Provided below are the top 16 holdings of the Fund as at December 31, 2016 – we don’t list the company names but, instead, provide a short description of each. You’ll see there’s not much overlap.

Final thoughts

Trimark Global Endeavour Fund has achieved both high absolute returns and risk-adjusted returns over the long term due to our process and discipline. Put another way, we didn’t achieve strong returns by taking huge risks “rolling the dice” and getting “lucky” on our investments only to see them “blow up” and have huge losses the next year.

We know that the investors in our fund work hard for their money, and after paying taxes and covering the costs of raising a family, it’s tough to save anything more. They’ve entrusted their savings to us and we feel that is an incredibly awesome responsibility. Unlike some fund managers who may play the relative-performance game to “keep up” with the market to maximize their year-end bonuses, we will not deviate from the strategy that has gotten us this far.

We don’t see numbers on a page, but rather people’s savings – whether for retirement or a child’s university education. We will not do foolish things like, in our opinion, pay high valuations to purchase stocks, invest in lower-quality companies with bad balance sheets or feel pressured to own something because it’s a big weighting in the index, just to “keep up” with the market.

We will also strive to remain humble and keep our emotions and egos in check. An old saying comes to mind: “A pat on the back is only 18 inches away from a kick in the butt.” Our discipline and focus may cause us to have periods where the Fund underperforms in the short term, but we aim to outperform over the long term. We like to think of investing as a game of golf – there may be times when we bogey a hole, but the focus is to win the tournament at the end of the day.

This post was originally published at Invesco Canada Blog

Copyright © Invesco Canada Blog