The future of ECB QE: Is the end in sight?

by Gareth Isaac, CIO, EMEA, Invesco Canada

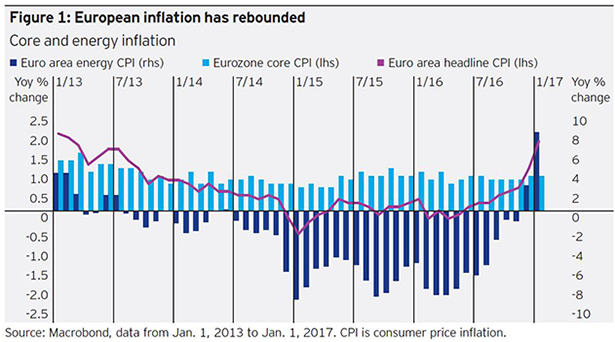

In recent months, consumer prices in the euro area have begun to align with the European Central Bank’s (ECB) inflation target of just under 2%.1 We expected January headline inflation to be around 1.8%, a far cry from the deflationary conditions that convinced the ECB to begin its asset purchase program (quantitative easing, or QE) in 2015 and then extend it in 2016. As we look forward to 2017 and beyond, we ask whether QE should extend beyond March 2018 or will the inflation hawks and external voices force the ECB to end it before the region is ready?

Why did the ECB adopt QE?

Unlike the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed), whose dual mandate is to foster both stable prices and sustainable employment, the ECB has one objective: price stability. In the past, this single mandate has led to some sub-optimal decisions by the ECB governing council, such as the move to raise interest rates shortly before the global financial crisis in 2008 and again before the European debt crisis in 2012. But in January 2015, it was in the name of price stability that ECB President Mario Draghi announced that the ECB would begin QE to shore up inflation expectations which had fallen sharply following a collapse in energy prices. It appears this move has paid off in terms of increased inflation and inflation expectations.

Critics suggest that QE has had limited direct impact on demand pull inflation, however. They argue that the primary transmission mechanism has been through the currency channel, meaning that any inflation rebound is likely to be temporary and due to higher imported prices fuelled by a weaker currency. Indeed, the ECB may have targeted a weaker euro to boost inflation expectations.

Should the ECB continue with QE?

Over the longer term, we believe it is difficult to see how inflation could remain at or around 2% without a continued fall in the exchange rate or rising energy prices. Eurozone wages remain stagnant, demographics in the region are challenging and high youth unemployment has depressed demand among those with a higher propensity to consume. Output gaps, although slowly closing, remain wide.

Besides macroeconomic considerations, tapering QE could reverse the sovereign bond spread compression seen across the eurozone. Since QE began, government bond yields have collapsed across the region, allowing countries to abandon austerity and finance deficits through cheap bond offerings. More recently, however, a combination of taper talk and political event risk has begun to weigh on spreads, especially in Italy and France where government bonds have underperformed.

Upcoming elections in France, Germany and the Netherlands in 2017 have raised market concerns that the anti-establishment backlash reflected in the Brexit vote and the U.S. presidential election could spread to Continental Europe. Budget deficits are still wide and although debt to GDP has stabilized in a number of indebted countries, higher interest rates could have a significant impact on debt sustainability in some countries. Since QE began in the second quarter of 2015, the ECB has been the primary buyer of European government debt. European pension funds have also been major buyers seeking to match increasingly onerous pension liabilities, but banks and asset managers have been selling. The popular peripheral Europe tightening trade favored by asset managers since the 2012 debt crisis has been exited, and only wider spreads will likely entice them back in without the backstop of ECB QE.

What could stop ECB QE?

President Trump’s administration has criticized some countries deemed to be targeting a weak exchange rate to improve the competitiveness of their domestic manufacturers. China has been the primary target but in recent weeks this theme has emerged regarding Germany. Germany’s current account surplus was USD280 billion in 2016 (9% of its GDP), higher even than that of China.2 The chief U.S. trade advisor has suggested that Germany has been the main beneficiary of a weaker euro, having seen its trade surplus with the U.S. more than triple since 2009 from EUR20 billion to almost EUR60 billion.3 There will likely be some nervousness in Germany that the U.S. may be preparing to cite Germany as a currency manipulator or at least continue to highlight the unfair advantage that German manufacturing enjoys due to a weak currency. The ECB may face pressure from Germany to rein in monetary policy to ensure that such calls are not made.

It is obvious that one single interest rate may not be appropriate for all countries; the current ECB deposit rate of -0.4% is likely far too low for Germany although it is probably appropriate for Italy and Portugal.1 Because weaker countries may not devalue their currencies independently, they are forced to regain competitiveness by reducing wages. Lower wages have led to lower demand and lower growth. No amount of bond buying will likely reverse that cycle. In Europe, when it comes to policy, one size does not fit all, and we believe that strains are beginning to show.

ConclusionOver the coming months we will likely see whether Mr. Draghi can continue to convince the ECB of the merits of continued QE or whether the northern European members win the day. We think it is worth considering the example of Japan. We believe there are a number of similarities between Japan and Europe. Both have weak growth, challenging demographics, low levels of immigration and are focused on inflation targeting.

The Bank of Japan was the first central bank to begin using QE as an unconventional monetary policy tool in 2001 and it is still trying a variation of it in 2017. At several junctures in the past, the government either declared victory and stopped QE too soon or tightened fiscal policy prematurely and the economy turned down again. We believe Japan’s experience should act as a salutary lesson to the ECB as it demands more austerity from Greece and deliberates on the future of QE in Europe. If not, the green shoots we have seen in terms of growth and inflation could wither very quickly when exposed to a post-QE reality.

This post was originally published at Invesco Canada Blog

Copyright © Invesco Canada Blog