by Kara Lilly, Investment Strategist, Mawer Investment Management, via The Art of Boring Blog

Society is often not kind to those who choose to be, or simply are, different. While we often look back fondly at the men and women who had the courage to look or think differently, this tendency obscures a simple fact: the act of standing out is typically unpleasant, even if it was the right thing to do.

Take, for example, Ludwig E. Boltzmann, a nineteenth century Austrian physicist. After decades of a productive career in the study of physics, Boltzmann began to publicly postulate a world in which atoms, and not energy (as commonly believed at the time), served as the foundation for the universe. He also started to identify entropy with probability. These ideas were revolutionary…and costly.

While Boltzmann’s insights would eventually become landmark achievements in physics, he would never live to see them accepted. Almost immediately upon introducing his theories, Boltzmann was shunned by his peers and the scientific community, as few believed in the existence of atoms or properly grasped the statistical nature of the work. For years, Boltzmann struggled to defend his theories—his life’s work—to his peers, but to no avail. He eventually succumbed to depression and took his own life on September 5, 1906.

As investors, knowing when to stick with our convictions vs. when to shift them is one of our greatest challenges. This is a balance that is difficult but important to strike; especially since “standing out” can be painful. So when and how should investors differ from the crowd?

Recently, I found myself on a plane seated next to the CEO of a major investment bank. He told me the story of how his senior currency strategist had made a big currency call. Apparently, when the strategist provided his initial forecast, the CEO encouraged him to go further…much further. “If you’re going to stand out,” he said, “you may as well go big. Then you’ll get media.”

Not surprisingly, the result was a very poor forecast but a lot of media coverage—a clear example of when standing out from the crowd was driven by, from our perspective, the wrong reasons.

Taking a stand

At Mawer, we tend to agree with the Stoics: step outside the crowd when integrity demands iti. For many ancient Greeks and Romans, there wasn’t any virtue in being different for the sake of being different or, for that matter, attention or glory. Standing out was warranted when it was the right thing to do.

In investing, there are going to be times when you should be at odds with the market and times when you should not. Knowing when you should be different is an important question to ask and, from our perspective, should be informed by your goals and principles.

As an example, our primary goal at our firm is to increase our clients’ wealth over time by investing in companies that compound wealth at attractive rates while taking a modest amount of risk. This goal governs all of our decisions and results in us being index agnostic. And because we do not make decisions in our portfolios based on the weight a particular company, sector or geography might represent in an index, our portfolios frequently differ from traditional market-capitalization weighted benchmarks.

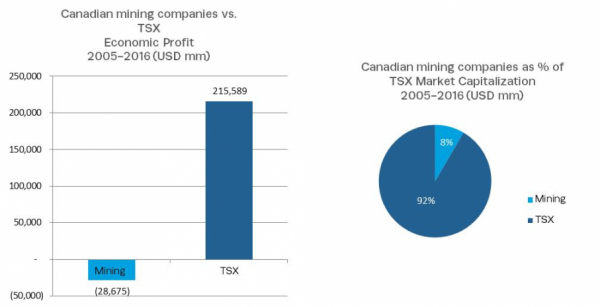

The mining sector is a good example of this. We frequently have no exposure to this sector as, in our opinion, mining companies generally make poor long-term investments. They require substantive upfront capital investment, sell commodity products over which they have no control of price, and often operate with a significant amount of debt. It is rare that they are sustainably wealth creating or that their valuations appear adequate enough to compensate investors for the volatility of their cash flows. So, we tend not to own these businesses.

In our portfolios there are many examples where we differ from the indices. This does not reflect a call on a specific sector or region; it’s simply a reflection of our bottom-up process of selecting companies that can compound wealth over time. We are not overtly trying to be contrarian; it just shakes out this way sometimes.

In our portfolios there are many examples where we differ from the indices. This does not reflect a call on a specific sector or region; it’s simply a reflection of our bottom-up process of selecting companies that can compound wealth over time. We are not overtly trying to be contrarian; it just shakes out this way sometimes.

The above graphs show the difference between the amount of wealth being created by the mining sector in Canada, as a percentage of overall economic value add created, versus the percentage of market capitalization this sector represents in the TSX. Clearly, market capitalization does not equal wealth creation.ii

For us, it makes sense that we look different from the index in these situations. Looking the same would inherently violate our core investment principles. Of course, your goals/principles may be very different from ours. Regardless, they should dictate when to take positions that are different from the crowd.

Knowing when to shift

“When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do sir?”

—John Maynard Keynesiii

The following transcript was said to have been recorded between a U.S. naval ship and the Canadian authorities off the coast of Newfoundland:

Americans: Please divert your course 15 degrees to the North to avoid a collision.

Canadians: Recommend you divert YOUR course 15 degrees to the South to avoid a collision.

Americans: This is the captain of a U.S. Navy ship. I say again, divert YOUR course.

Canadians: No, I say again, you divert YOUR course.

Americans: THIS IS THE AIRCRAFT CARRIER USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN, THE SECOND LARGEST SHIP IN THE UNITED STATES’ ATLANTIC FLEET. WE ARE ACCOMPANIED BY THREE DESTROYERS, THREE CRUISERS AND NUMEROUS SUPPORT VESSELS. I DEMAND THAT YOU CHANGE YOUR COURSE 15 DEGREES NORTH. THAT’S ONE-FIVE DEGREES NORTH, OR COUNTER MEASURES WILL BE UNDERTAKEN TO ENSURE THE SAFETY OF THIS SHIP.

Canadians: This is a lighthouse. Your call.

While the above example is an old (Canadian) joke, it is nevertheless instructive. One of the hardest things to do as an investor is to admit that you may be mistaken about a stock. Yet it is an essential skill, as failing to shift when it matters can be destructive.

One of the most underappreciated truths in investing is how difficult it is (if not impossible) to know if your investment hypothesis is correct. It is so easy to delude yourself into thinking that you know something more than the market. So how do we cope with the frailty of knowledge inherent in markets? In three ways. First, we acknowledge that there are many areas in which it is irrational to have a strong conviction one way or another. We must appreciate when we do/do not have an edge and act accordingly. Second, we must have high standards of conviction for our position. Facts and logic really matter. Moreover, it is prudent not to trust in one source of information but to go the extra mile, dig for more information and always fact check. Third, we must be ready to change our minds when information is uncovered that shifts the odds or falsifies our previous hypothesis.

This third point is critical and yet enormously difficult. It takes practice and deliberate effort to shift when necessary. Our history with Slater & Gordon is a good example.

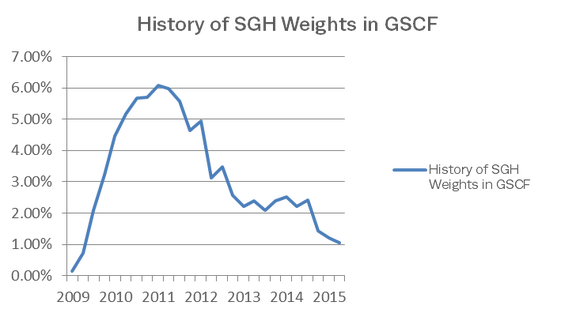

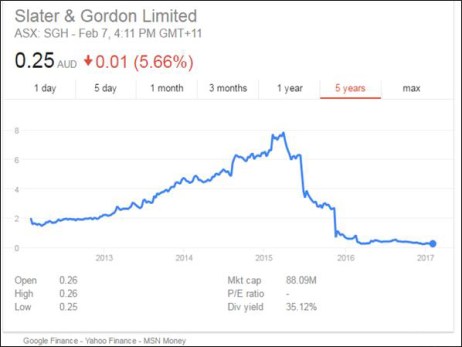

In 2010, I flew down to Australia for a research trip where I was scheduled to meet with dozens of management teams. Among them was the world’s first publicly traded law firm, Slater & Gordon (SGH).

The Global Small Cap Fund (GSCF) originally invested in SGH in 2008 at $1.60 per share. For years, the company appeared to be the kind of business in which we invest: one with a strong competitive moat and the ability to generate wealth over time. SGH’s core business was the Australian personal injury (PI) market, where the company had the dominant position, and management had added value to the business over time through small, tuck-in acquisitions of PI firms in Australia. We built up our position over time, even participating in some of the capital raises from the company. In 2013, SGH was the best performing stock in Australia, rising 128%.

But things began to shift over the years as the company made increasingly large and out of scope acquisitions. By 2013, we had become concerned about the quality of their business model given the erosion in capital conversion and management’s ability to execute on its acquisition-based strategy. By 2014, we were critical of the company’s aggressive accounting. Finally, in 2015, our team completely lost confidence in management after the announcement of a controversial acquisition and a forensic accounting review identified 17 red flags. This prompted Paul Moroz, co-manager of the GSCF, to call his counterpart, Christian Deckart, over to the Bloomberg terminal to say “we need to sell.”

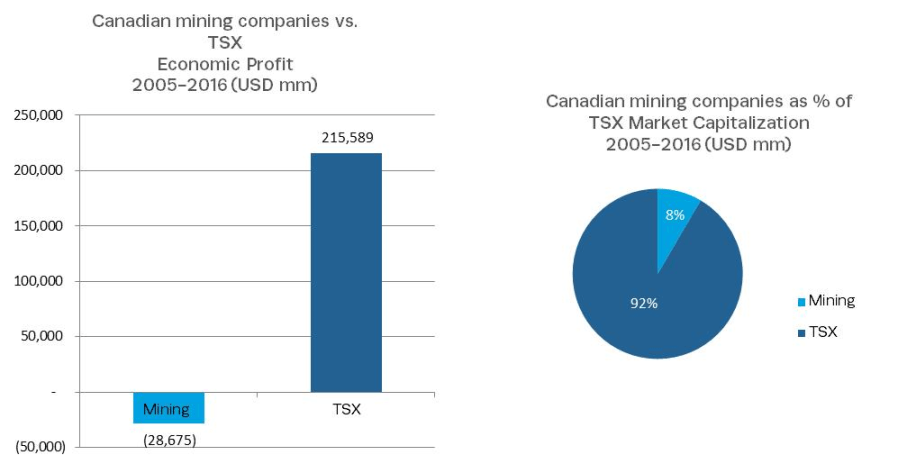

Our ability to shift our thinking on SGH heavily influenced our experience with this stock. By the point the Global Small Cap team made the decision to fully exit SGH, the position had already been brought down materially. In 2010, the stock had amounted to as much as 6.07% of the portfolio, but by the end of 2014, the stock had been taken down to around 1.21%. The shifts over time coincided with incoming information that undermined the hypothesis that this was a wealth-generating business.

At the time of this writing, SGH trades around AUD 0.30 per share. The company ended up writing off AUD 958 million from the controversial acquisition after only a year. In the end, the GSCF purchased its shares for an average price of AUD 1.75 and sold for an average price of AUD 4.50, before collection of dividends. Had we not been willing to change our minds, this ending would have looked very different.

Inevitably there will be times when you, as an investor, are standing apart from the crowd and it’s not working in your favour. In these cases, it’s difficult to know who is right: you or the market. In such situations, we have found the following approach useful:

- First, pause. Try not to make a move in either direction. Sometimes, it can feel necessary to “protect” your thesis (and your “smarts”) by doubling down on your original position or ignoring new information. But ignoring the market can be risky. This is why some portfolio managers have rules about not adding to losers in their portfolios. Immediately doubling down can be painful.

- Second, be aware of the conflicting evidence—the evidence that helped to support your initial thesis versus the fact that a lot of people still disagree with you (why is that?).

- It helps to take a Bayesian approach. Bayesian inference is a method, using Bayes’ theoremiv, to update the probability of a hypothesis as more information becomes available. Essentially, this approach asks: how does my view of the probabilities change, now that have I have this new piece of evidence?

- Third, embrace your paranoia. Ask yourself: what are we missing? Sometimes the market is myopic and missing the bigger picture. Other times, you may be the short-sighted one.There are many situations in investing where strong conviction isn’t warranted. But when you find that all evidence and logic points in one direction, and you just can’t come to a different conclusion, then it might be appropriate to stand firm—even when it’s difficult.

It’s Hard to be Different

In 1965, there was a little girl that lived on a farm in southern Ontario. Every day, this little girl with would walk five miles to school in her little blue jeans, which were more often than not covered in mud. When she would get there, she would cower at her desk and pray the teacher wouldn’t call on her. Often, however, she would be asked to read what was on the board.

“I saw outside today,” the little girl might say.

“No, Donna.” The teacher would sigh. “No, no, no. It says: I was outside today. Are you dumb?” The little girl would shrink at her desk, red in the face, as the other students giggled. She hated “was” because she always read it as “saw.”

That little girl was my stepmother. Decades after she left school, my stepmother learned that she had Dyslexia. Unfortunately, Dyslexia was not a recognized condition in the Peterborough school system when my stepmother was eight. As a result, she was frequently punished by teachers for disrupting the classroom and mocked by her peers. But Donna was not stupid. She simply did not see the words as others saw them.

It would be very easy to say “just be different when you should be” in this piece and leave the topic there. However, doing so would dismiss the emotional weight that we often feel when pushed to conform. Most of us have experienced a moment in our lives when we, or someone we know, ventured to be different and paid a price for it. For those of us who are active in markets, invariably we will feel pressure at times when the market is against us.

The story of my stepmother is interesting for two reasons. First, the objective reality was that the teacher had written the word “was” on the board, yet all Donna could see was “saw.” Unfortunately, her brain was not configured properly to see what the others could see, and there was nothing she could do about this. We need to realize that what seems very true to us may, at times, not be so.

Second, my stepmother was shown very little mercy for being different. She was eight, after all, and being outright ridiculed by an adult in front of her peers. This hurt. Over time, Donna learned not to let her happiness depend on the opinion of others. She would rely, instead, on managing her own thoughts and perceptions. Sure, it was a harsh way to learn, but this lesson has served her well over the years. To this day, Donna will tell me not to worry about things that are not in my control (like the opinions of others) and that no one can make me feel a certain way other than myself.

Strategies

In those moments in life when you need to stand apart from the crowd, we have found the following three strategies to be invaluable.

The first is to simply stay true to your goals and principles. Principles are the anchor that ground us in the storm. Without them, we are apt to be pushed around by the influence of others. Staying true to our investment philosophy and process has, over the years, saved our team from making decisions that would have turned out poorly in retrospect. Principles certainly helped guide our decisions with a stock like Slater & Gordon. And staying true to her principles helped someone like Donna be kind and good-hearted even when being attacked by others.

The second is to surround yourself with the right people. In the case of our firm, we are fortunate enough to work with clients and firm owners that keep the long-term in mind. Our clients understand that we will not sacrifice long-term success in order to chase short-term performance. Meanwhile, our ownership group ensures that we are always focused on staying true to our core values. Aligning yourself with people who share your goals and principles makes it easier when faced with external pressures. A little community can be a great source of courage.

The third is to reduce the role of ego in your life. The problem with ego is that it creates fragility. If you are too caught up in what others think, or looking good, the pressure of looking foolish or being embarrassed in front of a crowd can be insurmountable. It can be difficult to say things that outright disagree with the masses, even though you might need to. Our team is able to withstand months or even years of the market making us look foolish, in part, because we are more concerned with the truth than looking right. And we believe that this approach is best aligned with long-term success. To this day, I am willing to put myself out there and try (sometimes repeatedly) in situations in which I may look very foolish because of Donna’s example. I would rather risk embarrassment than have to tell her I chickened out.

Final Thoughts

In 1897, Boltzmann is said to have written down on some lecture notes: “Bring forward what is true. Write it so that it is clear. Defend it to your last breath!”v

The challenge of knowing when to shift and when to stand by your convictions is among the trickiest in this business. Clearly it is necessary to stand by your convictions, even if they disagree with the prevailing view of the masses. But, as Donna experienced, knowing what is “true” can be enormously challenging. Therefore, it is necessary to maintain much intellectual humility when considering how much conviction to put behind your beliefs. Sometimes it is necessary to change course.

But when it is time to stand apart from the crowd, know that the experience may not be pleasant. It is best to walk into these moments bracing for this to be the case—and keeping in mind the things that really matter in the end.

i See Seneca’s Letters from a Stoic or Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations.

ii The graphs evaluate the companies in the Canadian mining sector versus the TSX over an 11 year period. Results are shown in millions of USD and are achieved using an EVA approach to economic profit. Data is sourced from CFROI. The data set does not cover the full TSX, only the companies CFROI has data on (which accounts for approximately 80% of the index and the largest companies).

iii This quotation has historically been attributed to Keynes.

iv Bayes’ theorem is stated mathematically as the following equation:

where A and B are events and P(B) ≠ 0.

- P(A) and P(B) are the probabilities of observing A and B without regard to each other.

- P(A | B), a conditional probability, is the probability of observing event A given that B is true.

- P(B | A) is the probability of observing event B given that A is true.

This post was originally published at Mawer Investment Management