by Nathan Faber, Newfound Research

This blog post is available for download as a PDF here.

Summary

- The behavior gap is the difference between the returns on an investment and the returns that an investor realizes in that investment.

- Behavioral biases ingrained in human nature, such as anchoring, hindsight, and overconfidence drive emotional decisions that can lead to a behavior gap, but quantitative assessments of investor underperformance is often misleading, especially on an aggregated basis.

- Widely accepted disciplined investment methods, including regular investment contributions and withdrawals driven by financial constraints, can result in a perceived behavior gap depending on the market environment.

- Systematic momentum strategies used for risk management even exhibit behavior gaps when not viewed in the appropriate context.

- While the concept of a behavior gap is a good reminder that investor behavior can be detrimental to portfolio performance, investors are better served by developing a disciplined investment process they can adhere to, focusing on achieving goals rather than beating possibly non-applicable benchmarks.

We can all likely make a list of behavioral biases that we have fallen prey to at some point in our lives, especially when reflecting on poor decisions. And if we can’t identify any, we might need to start the list with conservatism bias[1].

Investing may be one of the best examples of where the consequences of these biases are most felt. Whether it is overconfidence and misjudging risk, mistaking randomness for patterns, anchoring to a specific price, or using perfect hindsight to assess past choices, emotional decisions often lead to unsatisfactory investment outcomes.

When these biases manifest themselves in investments, we get the behavior gap: the difference between the return an investment generates and the return an investor actually realizes on that investment.

Source: “The Behavior Gap” by Carl Richards

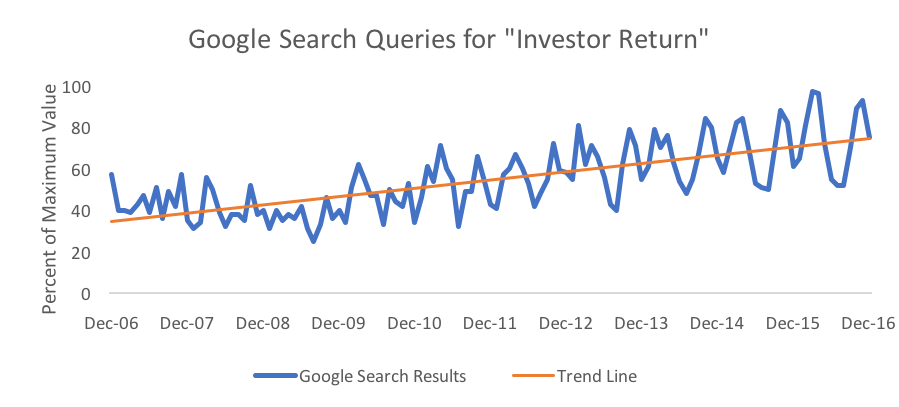

Over the past decade there has been an upward trend in Google Search queries for “investor return,” suggesting that the idea has come more into the limelight. In our view, this trend indicates that investors may not have benefitted from the current bull market to the extent they expected.

Source: Google Trends.

With a single investment or portfolio for one individual, quantifying and interpreting the behavior gap is simple. The timing of intermediate cash flows drives return differences relative to what would have been realized with a single lump sum investment.

Aggregating behavior across investments and interpreting the results is a bit more difficult. Despite this, numerous reports of aggregated behavior gap results are circulated. For instance, a study of 8,000+ German investors found that their behavior gap was over 7.5% per year from September 2005 to April 2010.[2]

And that was before trading costs.

Naturally, these daunting results are used in marketing materials to highlight why investors need specific products for closing the behavior gap.

But before we get to our take on closing behavior gaps, what if we are wrong about the detrimental impact of investor behavior?

Recent Reports on Investor Behavior

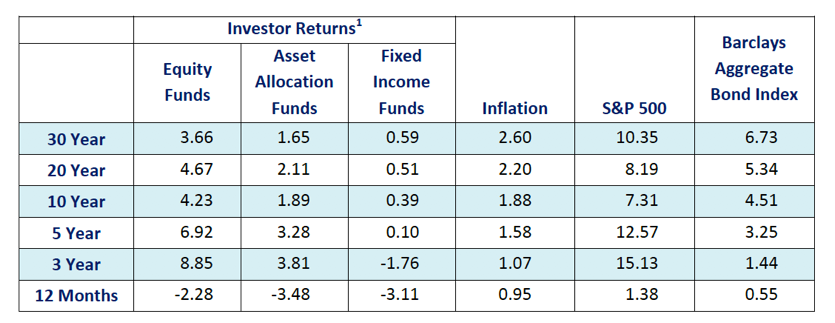

DALBAR’s Annual Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB) is generally the go to source for data quantifying just how bad investors are at timing investments.

In the report, they calculate the dollar-weighted average return for investors in mutual funds, classified as either equity, fixed income, or asset allocation.

The results in the report are not pretty compared to the benchmarks shown.

Source: DALBAR’s 22nd Annual Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior. Data as of 12/31/2015.

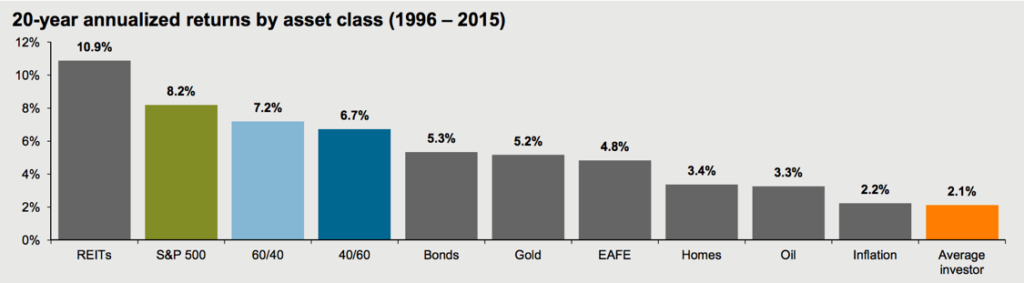

J.P. Morgan even uses this data in their very informative Guide to the Markets as the “Average Investor” return.

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management

But these results compare mutual funds to the S&P 500 and the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index, which hardly seems fair given the fact that many of these mutual funds are most certainly diversified across size, style, geography, credit, and other betas.

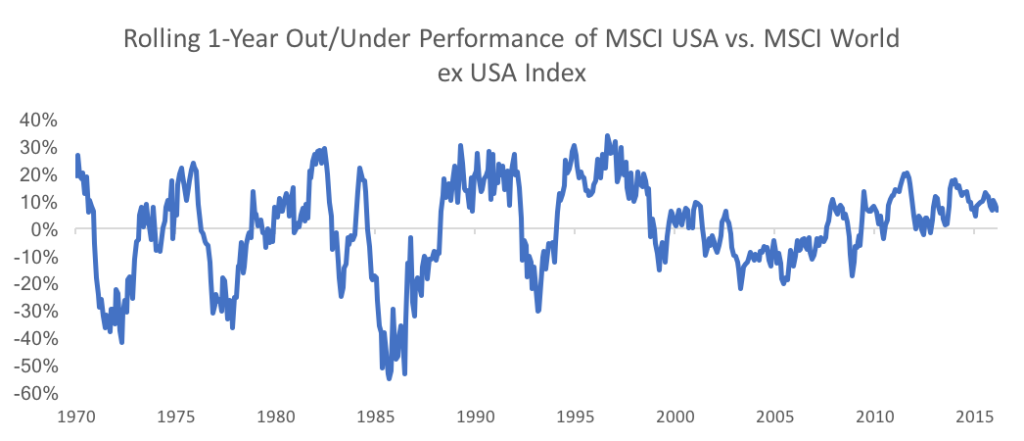

Even passive investments in U.S. and international large-cap equities have exhibited wide annual performance differences. Given that the U.S equity market outperformed the international equity market in 55% of rolling 1-year periods with an average excess annualized return of 135 bp over the entire period, we would intuitively expect a combination of the two to underperform the U.S. equity benchmark even with complete investor discipline. This is simply diversification in action.

Source: MSCI. Calculations by Newfound. Data as of 1/31/2017. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Additionally, comparing mutual funds to indices neglects the impact of fees. While fees are an important part of the picture when evaluating investor returns, they can skew the perceived effect of investor behavior.

Accurate benchmarks are important to accurately assess investor returns.

Comparing Apples to Apples

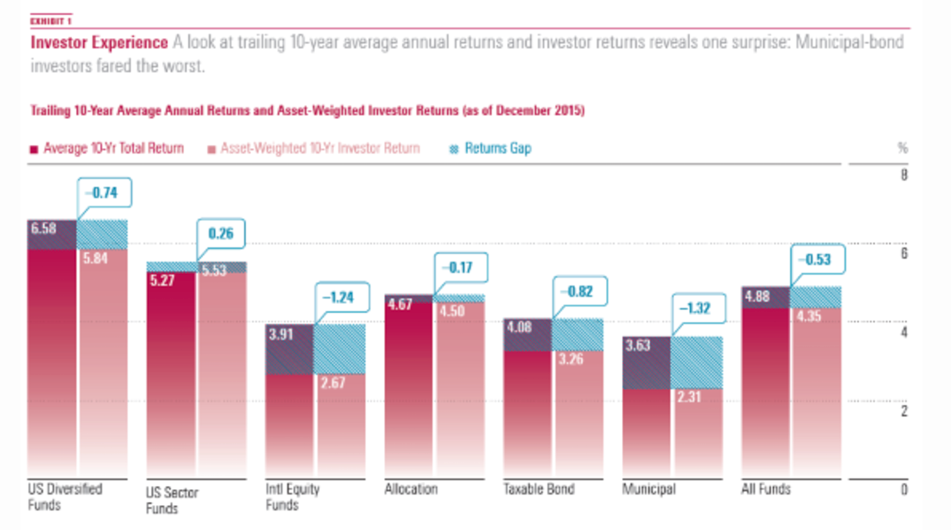

Morningstar solves these specific issues by comparing investor returns in a fund to the return of the same fund. When they aggregate up by asset class, the investor returns and the benchmark returns are scaled by the fund size, thereby isolating the investor behavior gap from benchmark selection affects.

Source: Morningstar. Data as of 12/31/2015. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Now the picture looks a bit different. Over the same ten years that DALBAR’s report showed a 308 bps behavior gap in equity funds and 412 bps in bond funds, Morningstar is only showing behavior gaps of up to 132 bps. In the case of U.S. sector funds, the investor return actually eclipsed the investment return.

Investor behavior may not deserve the reprimand it has historically gotten.

Even Morningstar’s improved methodology, however, does not paint the full picture, as even disciplined investors may show a behavior gap with this broad analysis.

Netting out Discipline

Inherent to the DALBAR report and Morningstar results is the premise that all mutual fund flows are driven solely by investor choices. In reality, investors operate in a world of financial constraints.

Younger investors typically do not have a lump sum to invest at the very beginning of the time period, which is required to realize a purely passive, time-weighted return. Investors in retirement are generally taking withdrawals from their nest egg and may only have limited flexibility to postpone or scale back these outflows.

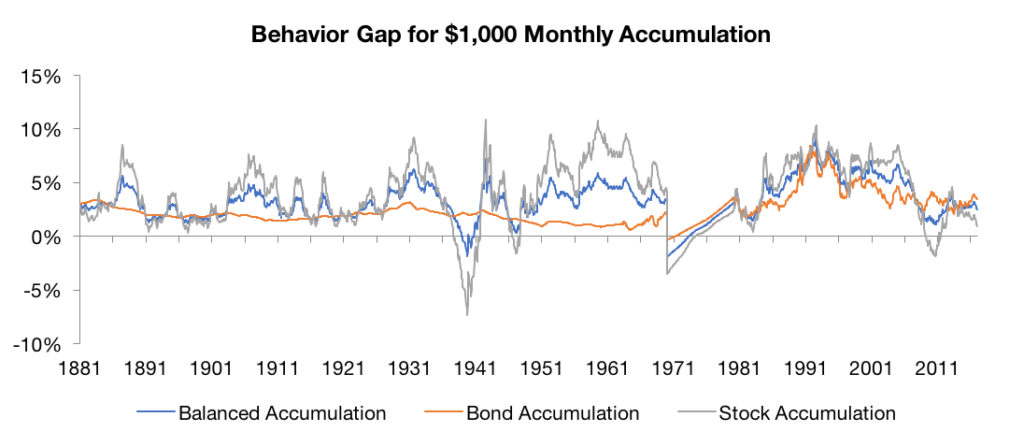

Consider two simple mutual funds: one that invests in the S&P 500 and one that invests in 10-year U.S. Treasuries. Our investors in this two fund world are Accumulation Arnie and Withdrawal Wilma.

Arnie recently started his first job fresh out of college. He is saving diligently, setting aside $1,000 per month into his retirement account.

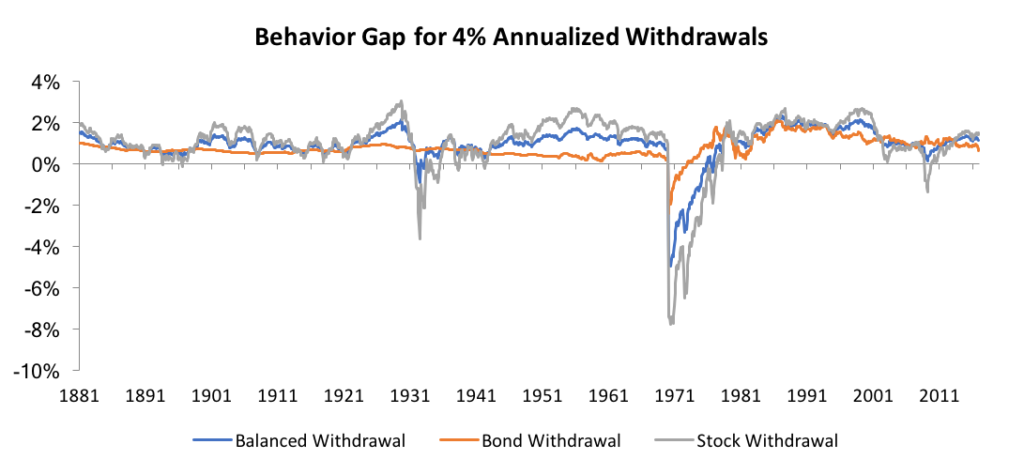

Withdrawal Wilma is enjoying her retirement, following the conventional wisdom of withdrawing 4% of her account balance annually.

Below we plot the “behavior gap” that their investment processes would have caused over rolling 10-year periods compared to passive investments in the S&P 500 (“Stock”), 10-year U.S. Treasuries (“Bond”), and a 50/50 mix of the two (“Balanced”).

As a reminder, a positive behavior gap is a bad thing, as it implies that the investor flows underperformed a buy-and-hold approach.

(Note: While an investor in the accumulation phase would very rarely allocate only to bonds and an investor in the withdrawal phase would very rarely allocate only to equities, these scenarios were chosen to highlight the extremes.)

Source: Robert Shiller. Calculations by Newfound. Data as of 12/31/2016. “Stock” refers to the S&P 500, “Bond” refers to a 10-year U.S. Treasury constant maturity index, and “Balanced” refers to a 50/50 blend of the two. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

| Balanced | Bond | Stock | |

| Average Behavior Gap | 3.3% | 2.4% | 3.8% |

| % Positive Periods | 96.2% | 99.1% | 91.5% |

Source: Robert Shiller. Calculations by Newfound. Data as of 12/31/2016. “Stock” refers to the S&P 500, “Bond” refers to a 10-year U.S. Treasury constant maturity index, and “Balanced” refers to a 50/50 blend of the two. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

| Balanced | Bond | Stock | |

| Average Behavior Gap | 0.9% | 0.8% | 1.0% |

| % Positive Periods | 94.7% | 97.9% | 90.3% |

In both examples, the behavior gap existed over most of the 10-year periods. Yet, these investors were behaving rationally.

This is largely a consequence of the fact that both equity and bonds markets have appreciated over the time period studied. When investors make contributions in a rising market, those later contributions do not earn as much as an initial lump sum would have.

Similarly, when investors take distributions in a rising market, those distributions miss out on subsequent gains.[3]

Compared to investors at other times, were investors who started accumulating or withdrawing before the Great Depression, the early 1970s, or the Financial Crisis more disciplined because they had a negative behavior gap? We don’t think so. They were just lucky.

Financial constraints should not be misconstrued as bad investor behavior.

Netting out Objectives

Now let’s move to a systematic strategy, one that relies on momentum to manage risk.

Each month, we will invest in the S&P 500 when it closes above its 10-month simple moving average (SMA) and invest in 0% interest cash when it closes below the SMA.

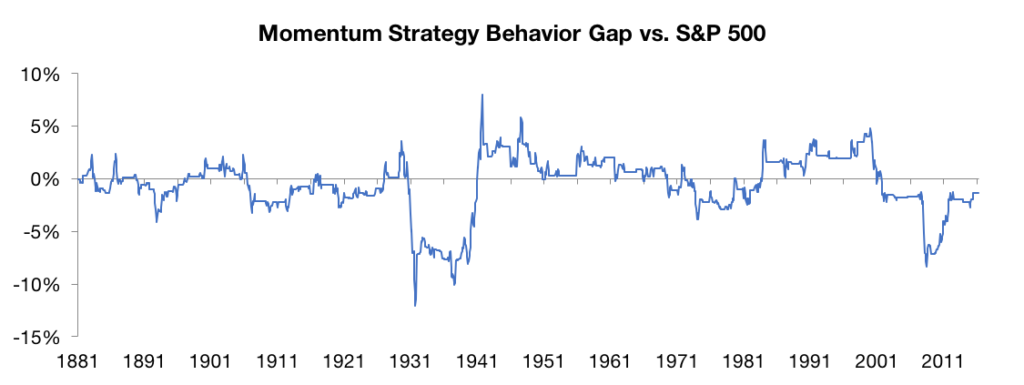

We see the familiar “behavior gap” emerge in 47% of rolling 10-year periods when compared against a buy-and-hold investment in the S&P 500.

Source: Robert Shiller. Calculations by Newfound. Data as of 12/31/2016. Momentum strategy is hypothetical and backtested and does not represent any Newfound strategy or index. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

But it is all a matter of perspective.

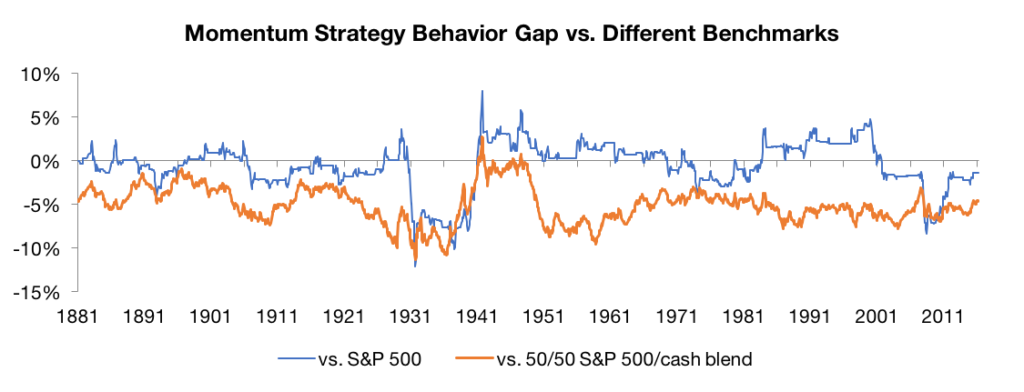

A tactical strategy like this is best benchmarked against a 50/50 mix of the S&P 500 and cash. This allows outperformance to be measured whether the strategy makes the right call on the up or downside. Using only the S&P 500 means the strategy is always playing catch-up, especially since markets have historically increased.

When we calculate the behavior gap versus this blended benchmark, we get a different picture.

Source: Robert Shiller. Calculations by Newfound. Data as of 12/31/2016. Momentum strategy is hypothetical and backtested and does not represent any Newfound strategy or index. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Our investor is now exhibiting excellent behavior. The number of rolling 10-year periods with positive behavior gaps has dropped from 47% to less than 1%.

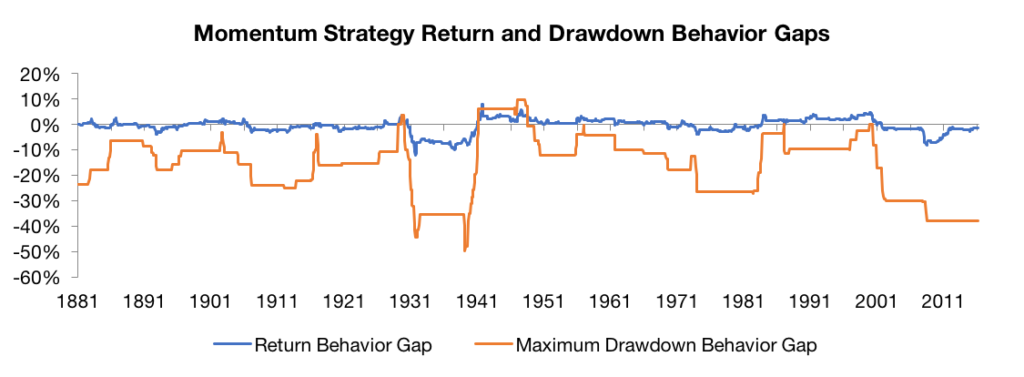

Viewed a different way, we could keep the benchmark as the S&P 500 but recognize that a key objective of a tactical equity strategy is risk management relative to the S&P 500. Calculating the drawdown behavior gap shows that a small hit to returns generally resulted in a significant drawdown reduction.

Source: Robert Shiller. Calculations by Newfound. Data as of 12/31/2016. Momentum strategy is hypothetical and backtested and does not represent any Newfound strategy or index. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

The drawdown behavior gap and return behavior gap were both positive – implying that drawdowns were higher and returns were lower - in only 6% of rolling 10-year periods.

Do We Really Care About the Average Behavior Gap?

Averages are a great tool in many areas of finance, but they obscure other possibilities lurking behind the behavior gap. Characteristics of the behavior gap distribution can shed more light on how investors are actually doing.

Consider an investor who has a series of cash flows in a fund. Now consider their counterpart who has the exact opposite series of cash flows into the fund.

By definition, the aggregated investor return is equal to the investment return since the net cash flows are zero. The split of luck and skill between these two investors can only be judged by looking at each investor separately and their reasons for the cash flows.

We can also generalize this to more than two investors. One thousand investors with small behavior gaps can be offset by one investor negating their cash flows, or vice versa.

Perfectly offsetting behavior among investors mistakenly shows perfect investor behavior even if the majority of individuals have positive or negative behavior gaps.

How Can You Assess the Behavior Gap?

With all these nuances, how does one interpret the investor behavior assessments that frequently appear in articles and marketing?

If you are examining investor returns for a specific fund or for a broad basket of investments, we believe there are three key ways to give appropriate context to the reported behavior gap.

- Look at what the investment is.

Is this a target date retirement fund in which investors are not likely trying to time their cash flows? Or is this a boutique fund that frequently goes in and out of favor with investors (e.g. volatile alternatives or niche ETFs)? In the former case, a behavior gap may be created by contributions; in the latter, it may truly be a case of performance chasing.

- Look at the benchmarks.

Is the benchmark appropriate? Did the benchmark go through significant bull and bear periods that could lead to skewed results for investors who were dollar-cost averaging?

- Look at how assets grew.

Did the fund grow over time because it was new? Were there any extreme flows that may have a non-behavioral explanation (e.g. seed capital or institutional investments)? Large investments relative to fund size can skew otherwise good (or bad) investor behavior depending on when flows occurred.

Conclusion

We definitely believe that the biases the behavior gap sets out to highlight are real and that eliminating them is a constant battle for investors. Rather than relying on broad generalizations on the effects of “investor behavior”, focusing on individual situations and objectives is the best way to nip any detrimental tendencies in the bud.

With the ultimate goal of encouraging investors to develop and stick to a plan, simply showing them an aggregate behavior gap without providing the appropriate context of their own investment process and life situation may be counterproductive.

Systematic investing is our primary way of addressing the biases that lead to a large behavior gap. With a well-defined process grounded in theory and supported by empirical evidence, we aim to remove the temptation to make emotional decisions.

At its core, the argument that a large behavior gap comes solely from investors’ poor decisions is fallacious. The stripped down form the argument is:

If investors always behave badly, then the investor return is lower than the investment return.

The investor return is lower than the investment return.

Therefore, investors always behave badly.

This would be like saying:

If I am the CEO of BlackRock, then my company provides investment strategies.

My company provides investment strategies.

Therefore, I am the CEO of BlackRock.

Watch out Larry Fink.

[1] Conservatism bias is the tendency to revise our beliefs insufficiently when presented with new evidence.

[2] Meyer, Steffen and Schmoltzi, Dennis and Stammschulte, Christian and Kaesler, Simon and Loos, Benjamin and Hackethal, Andreas, Just Unlucky? – A Bootstrapping Simulation to Measure Skill in Individual Investors’ Investment Performance (June 6, 2012). This figure includes underlying fund fees.

[3] This is not to say that dollar-cost averaging is bad. It is perfectly acceptable for mitigating timing risk when the financial flexibility exists to do so. However, it will reduce returns when markets are increasing.

Copyright © Newfound Research