by Ben Inker, GMO LLC

The new administration’s plan for a large fiscal stimulus seems poorly designed, oddly timed, and very unlikely to produce the sustained strong growth that Trump claims he will provide. Even in the unlikely possibility that we do achieve the growth Trump is calling for, it is not obvious that it would be the boon to the stock market that investors seem to think. The fiscal stimulus does, however, seem likely to lead to tighter monetary policy and has a reasonable chance of leading to rising inflation. How the economy responds to these two potential outcomes will tell us a good deal about whether the Hell or Purgatory scenario is correct, which will be helpful to investors even if the policies themselves prove not to be.

Introduction

Last quarter’s letter, “Hellish Choices: What’s An Asset Owner To Do?” discussed what I consider to be the most momentous investment question facing asset owners today. Will asset prices revert to valuation levels similar to historical norms, leading to bad returns for a while but long-term returns similar to what investors have been trained to expect? Or have we seen a permanent shift such that asset class valuations have permanently risen and long-term returns available from them have consequently fallen? Such a shift would be a profound problem for the basic rules of thumb used by almost all long-term investors, but in the shorter run means returns will not be disastrously bad. The key metric that I believe has driven market valuations upward in recent years and could conceivably drive them right back down is short-term interest rates: So much of this comes down to a question of whether cash rates over the next 10, 20, or 50 years will look like the “old normal” of 1-2% above inflation or whether they will look more like the average of the last 15 years of about 0% after inflation. The scenario where they average 0% real is what we have referred to as “Hell,” whereas the other scenario is “Purgatory.” On the eve of the US election in November, the US 10-year Treasury Note was yielding about 1.55%, which suggested the bond market at least was very much in the Hell camp. As of year-end, that yield has risen 90 basis points to 2.45%, which is at least closer to a level consistent with Purgatory. This has led a number of our clients to ask us if we have changed our minds about the likelihood of Hell, as the market seems to have. The short answer is that we have not. If Hell is a permanent condition for markets, it should not be readily changeable by the policy choices of a single US administration, to say nothing of the fact that we do not yet know what those policy choices will be for an administration that has just taken office.

But the basic dilemma of “Hellish Choices” was not strictly about Hell, it was about the uncertainty as to whether we are in Hell or Purgatory, given the two have quite different implications for both portfolios today and institutional choices for the future. Keeping with the theological theme, I will call that state of uncertainty “Limbo.” A certain unpleasant outcome is not something to be excited about, but it is at least something you can try to prepare for. Uncertainty that has important implications for your portfolio is another matter entirely, and the most important implication of the Trump administration is not that it has removed the possibility of Hell from our investment forecasts, but that it gives us some hope that we may be able to figure out whether we are in Purgatory or Hell within the next few years. That does, at least, get us out of Limbo.

Two scenarios for how we got here

It is certainly the case that bond yields are becoming more consistent with a Purgatory outcome and the Fed’s “Dot Plot” was always consistent with it, but it was never really the Fed or the bond market that made us reluctantly contemplate a future of permanently low interest rates. Rather, it has been the extended period of time in which extremely low interest rates, quantitative easing, and other expansionary monetary policies have failed to either push real economic activity materially higher or cause inflation to rise. The establishment macroeconomic theory says one or the other or both should have happened by now. It seems to us that there are two basic possibilities for why the theory was wrong. The first is a secular stagnation explanation of the type proposed by Larry Summers and others.1 This line of argument can be boiled down to saying that the reason why exceptionally easy monetary policy has not been particularly stimulative and/or inflationary is that the “natural” rate of interest has fallen to extremely low levels relative to history. This means that the apparently extremely easy monetary policy has not, in fact, been particularly easy. Consequently, we should not have expected a huge response from the economy or prices. If this argument is correct (and secular stagnation is a reasonably permanent condition for the developed world, not just a temporary effect of the 2008-9 financial crisis), then we should see that as interest rates rise to levels that are still low by historical standards, they will choke off economic growth. Part of the plausibility of this argument comes from the fact that debt levels have grown steadily and massively in most of the developed world over the last 30 years, so it is easy to imagine that indebted households and corporations could run into problems if rates were to back up even 200 basis points from the recent lows.

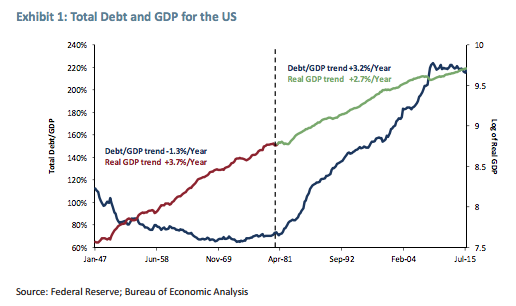

The second possibility for why extraordinarily easy monetary policy has not had the expected effects on the economy and prices is an even simpler one: Monetary policy simply isn’t that powerful. This line of argument (which Jeremy Grantham has written about a fair bit over the years) suggests that the reason why monetary policy hasn’t had the expected impact on the real economy is that monetary policy’s connection to the real economy is fairly tenuous. There is no question that monetary policy affects the financial economy. Corporations may or may not have changed their investment and R&D decisions based on the level of interest rates, but low rates have certainly encouraged borrowing to pay for stock buybacks. But, as Jeremy has pointed out, if debt increases and easy monetary policy are such a boon to economies, why haven’t we seen any boost to growth as debt has grown relative to GDP? Exhibit 1 is an old favorite of Jeremy’s, showing GDP growth and debt to GDP for the US over time. The build-up of debt since the 1980s certainly hasn’t coincided with a speed-up in GDP growth, or even evidence of an economy straining to run faster than its potential growth rate.

The secular stagnation argument implies there must be something important wrong with the economy such that even the build-up of debt hasn’t been able to get growth any higher than it has. The alternative explanation is that debt just doesn’t matter that much. The productive potential of the economy is built out of the skills and education of its workforce and the depth and technology of its capital stock. The way that capital stock was financed may be of academic interest, but has no bearing on what we can expect it to produce. If that is true, then the various ways monetary policy impacts the economy are unlikely to be that meaningful.

Implications of the two scenarios

So we have two competing hypotheses that can both explain how we got to this point. The nice thing is that they would have quite different implications as we go forward from here. If the secular stagnation theory is correct and equilibrium interest rates have fallen a lot, we should expect to see rising interest rates slow the economy considerably, and the Federal Reserve will find itself unable to raise rates as much as it is planning to. The economy will either slide back into recession, causing rates to come right back down, or we will settle into such a precarious low-growth mode that it will stop raising rates by the time we get to 2% or so on Fed Funds. Such an outcome would be at least suggestive that we are in Hell. But winding up in recession in the next couple of years is not an iron-clad guarantee we are in Hell. If it is possible for an expansion to die of old age, the current one is getting pretty old and might be due for death by natural causes. And there is also a meaningful possibility that either external events or other aspects of government policy – protectionist policies leading to a global trade war, perhaps – could push us back into recession. So cause of death for the expansion will be very important to know, should it occur.

If, on the other hand, the “monetary policy doesn’t matter” explanation holds true, then the economy has every reason to power through the Federal Reserve’s gradual rate rises without too much trouble. We probably will begin to read analyses of the financial crisis and the years after which suggest that while some of the emergency measures helped to get the banking system functioning again in the immediate aftermath of the crisis, quantitative easing and ultra-low interest rates did not do that much for the economy in the end. This will likely bleed into pieces pointing out that if monetary stimulus isn’t all that effective in boosting the real economy, it should be used sparingly because its impacts on the financial economy are very significant and generally negative for financial stability, given how it encourages leverage, speculation, and asset bubbles.2

If the economy remains reasonably strong, we should expect the Fed Funds rate to rise at least to the level of the “Dot Plot” of around 3%, and quite likely higher. This will, of course, push up bond yields. Higher bond yields will provide some competition for stocks in portfolios and the higher cost of debt will discourage corporations from taking on ever-increasing amounts of debt in order to buy back stock. P/Es may, at long last, come back down to levels consistent with their longer history of somewhere in the middle to upper teens. Investment portfolios will take a hit, but we will at least be back to a level of valuations where investors can expect to earn the kinds of returns they need in the long run. It will be Purgatory, and while Purgatory is painful, it is finite.

What if Trump succeeds?

This all assumes that the administration’s attempt to push the economy up to 3.5-4% growth fails, and that raises a couple of questions. First, why do we think the US economy is very unlikely to achieve sustained growth anything like 3.5-4%? And second, what happens if they actually succeed despite our misgivings?

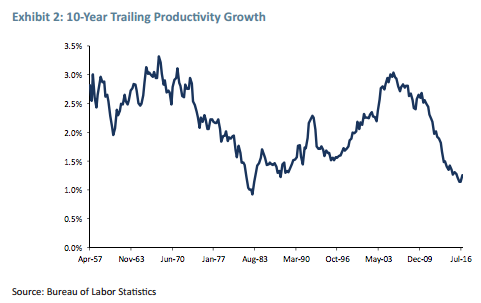

As to the first question, Janet Yellen pointed out politely in her December press conference that today seems like an odd time for a large fiscal stimulus. The unemployment rate is only 4.6%. While labor participation rates have fallen, the Economic Policy Institute estimates there are only about two million people who could be coaxed back into the workforce by a strong economy, and even a very optimistic reading of the data would put that number at around five million.3 A couple of million additional workers over a few years is nothing to sneeze at, but it should be remembered that such marginal workers would be unlikely to be particularly productive. In general, it is the least trained, productive, and employable who were the ones to drop out of the workforce, and they are likely to be employed in relatively low wage and output jobs if they are coaxed back in. And even if we can get those additional millions into the workforce, it would be a one-off benefit to GDP. It would be positive for society and probably consumers’ mood about the economy, and we can certainly hope it happens, but it would not be the key to sustained high growth. Sustained high growth in the context of a slowly growing population requires fast productivity growth, which the US economy has been particularly bad at delivering of late. Exhibit 2 shows 10-year trailing productivity growth in the US.

The current trend looks to be something south of 1.5%, and population growth is set to add somewhere between 0.2-0.5% to the workforce over the coming decade, absent a change in labor participation rates or a burst of immigration.4 While it is tempting to believe we can return to the 3% productivity growth that we saw for the decade ending in 2005, the reality is that is probably a pipe dream. The overwhelming driver of the spike in productivity in that decade was the extraordinary growth in production of IT equipment, which grew at 10% real per year for the decade ending in 2005, despite a declining number of people employed. Annualized productivity per worker in the industry was therefore a stunning 13%. Since then, technology hardware output has grown at a much more pedestrian 1.7% and output per worker a good, but less special, 4%. The subsequent breakdown of a number of the engineering “laws” governing the speed of progress in computing makes it seem extremely unlikely we will see a reacceleration of productivity growth in IT hardware production to anything like the earlier level.5 Deceleration looks more likely. Even the most plausible productivity breakthrough for the next 5-10 years, autonomous vehicles, seems much more likely to be a job killer than job creator.6

So, a massive reacceleration of productivity seems unlikely. And it’s possible that looking at the trailing 10-year number understates how slow productivity growth has gotten, as productivity over the last 3 and 5 years has averaged 0.7% and over the last 12 months a nice round 0%. Attempting to grow a 1.5-2% economy at 4% is a recipe for inflation, and this is where the Trump effect will help us answer questions much more quickly than we would with a president enacting more conventional policies.7 Any acceleration of inflation will require far faster interest rate increases than is generally being priced in and we will likely learn relatively quickly whether the economy can withstand those increases.

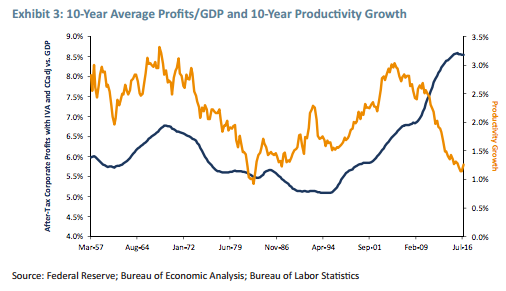

But if we assume for a minute that somehow the economy really does grow at 3.5-4%, this probably will not be the panacea for equity investors that some are assuming. First, it seems more or less impossible that the right interest rate level for an economy growing at 4% would be 0% real. So Hell, in that case, would seem to be off the table, and with it a big part of the justification for higher P/Es for the stock market. And while the faster growth would seem at first blush to be a big plus for equities – after all, it would mean that corporate revenues will grow significantly faster than they have been – our best guess is actually that faster growth might well be associated with a stock market trading at significantly lower valuations than today. The 1960s and 1996-2005 periods may have been the halcyon days of productivity in the US, but it is the current period that has been best for profitability, as we can see in Exhibit 3.

In both the 1960s and the 1996-2005 periods, profits were about 6.5% of GDP, against an average of 8.5% in the most recent decade. The slowdown in productivity growth certainly didn’t seem to hurt corporate profitability much, so it seems odd to assume that a hypothetical increase in productivity will push it up still higher. In fact, for an economy in which consumption is around 70% of output, one can make the argument that a necessary condition of sustained strong economic growth would be the share of income going to labor going up from here. This would almost certainly require corporate profits to fall as a percent of GDP. And if profit margins fall materially, even a moderate acceleration of revenue growth would lead to falling, not rising, overall profits.

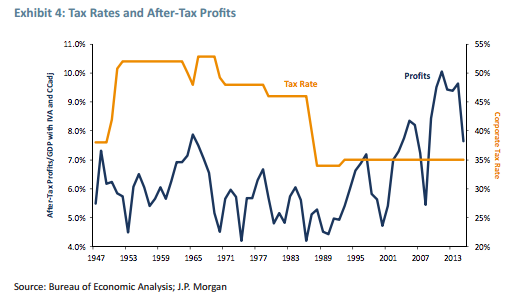

But what about the cut in corporate tax rates? Surely that will be a positive for the stock market? It is possible that it will be, but it is neither theoretically clear that it should be nor empirically obvious that tax rate changes have been particularly important to profitability. Exhibit 4 shows after-tax corporate profits versus corporate tax rates since 1947.

It’s hard to see a lot of correlation here. While tax rates are currently at about their lowest levels and corporate profits just off of their highest, tax rates did their falling in the 1980s and the profit spike was a good 20 years later. Given that lag, it strains credibility to argue that the tax rate fall was an important driver of the rising profitability. What you would want to see is a relationship such that when tax rates fall over a period, profits rise. This does not seem to have been the case, as the correlation between tax rate change and profit change as a percent of GDP is positive over 3-, 5-, 7-, and 10-year periods. This means that tax rate falls have generally been associated with falling, not rising, profits.8 Your microeconomics professor probably would have taught you that corporate taxes should be a passthrough, just as sales taxes are. Because corporations are interested in their after-tax return on capital, a change in corporate tax rates should generally affect output prices, not profits.9 That would make a fall in corporate tax rates at best a one-off windfall and possibly a wash.

It is easy to imagine that a burst of economic growth might create a stock market bubble, as occurred in the late 1990s. But in terms of what the stock market is actually worth, if faster growth leads to interest rates returning to historically normal levels, the safe bet is that equity valuations will eventually find their way back down to historically normal levels as well.

Conclusion

And this brings us back to the odd paradox about Purgatory and Hell. If Trump’s policies work or if they otherwise demonstrate that we are not stuck in secular stagnation, it’s bad for stocks and bonds and good for the economy. If we wind up back in recession, it’s good for bonds and not necessarily terrible for stocks because valuations can stay high, buoyed by low cash and bond rates.

It is hard to be particularly hopeful about the prospects of the incoming administration’s economic policies. Certainly, if they are predicated on an actual belief that the US economy can sustainably grow at 4%, they are more likely to lead to accelerating inflation than anything else. But there is a meaningful plus side to what Trump is doing. Whether he succeeds or fails, we are likely to learn some useful things about the economy and therefore where valuations will wind up in the coming years. While neither Hell nor Purgatory are particularly happy outcomes for investors, either one is arguably better than our current stay in Limbo, where it is difficult to even prepare for whichever future awaits us.

We are still putting the higher probability on the Purgatory outcome, which implies that rising rates will not kill the economy. But our collective confidence in that outcome is not close to high enough that it makes sense for that to be the only scenario we should be preparing our portfolios for. For now, we are still in Limbo and are focusing on making the best we can out of an uncertain investment landscape, building a portfolio that can survive either scenario. This means focusing first and foremost on those areas where we believe either leads to decent outcomes. Emerging market value stocks are first on that list, followed by alternatives such as merger arbitrage. After those come EAFE value stocks and US high quality stocks. At current yields, TIPS are a reasonable holding in multi-asset portfolios whether we are in Purgatory or Hell, although they do look a good deal better in Hell. Credit, while less exciting than it was a year ago by a good margin, fills out the list of assets that seem worth holding in either scenario. Other assets, such as broad US equities or developed market government bonds, seem hard to love in either of the plausible scenarios, and are consequently hard for us to want to hold.

Ben Inker. Mr. Inker is head of GMO’s Asset Allocation team and member of the GMO Board of Directors. He joined GMO in 1992 following the completion of his B.A. in Economics from Yale University. In his years at GMO, Mr. Inker has served as an analyst for the Quantitative Equity and Asset Allocation teams, as a portfolio manager of several equity and asset allocation portfolios, as co-head of International Quantitative Equities, and as CIO of Quantitative Developed Equities. He is a CFA charterholder.

1 See http://larrysummers.com/2016/02/17/the-age-of-secular-stagnation/ among other essays and speeches on the topic.

2 At the very least, you’d expect to read such pieces from us.

3 The official US labor participation rate is for the population aged 16 and higher. Given the growing segment of the population over 65, it would be very odd if this remained stable. Taking the prime working age cohort of 25-54, the current participation rate is 81.4%, versus its 25-year average of 82.8% and an all-time high of 84.6%. Moving that rate back up to the 25-year average would entail a total of about 2 million additional workers and recapturing the all-time high would require 5 million.

4 And among the things that seem quite unlikely under the new administration, significantly increased immigration has got to be pretty close to top of the list.

5 Specifically, Dennard scaling, which states that as transistors get smaller their power density stays constant, broke down in about 2006. Had it continued at its prior pace, the clock speed of a typical computer processor would be about 70 times what it currently is. More recently, the more famous Moore’s Law (i.e., that the number of transistors in a dense integrated circuit doubles approximately every two years), has begun to break down, with improvements in transistor density falling well off the old trend. The old rate of decrease in data storage costs (sometimes referred to as Kryder’s Law) has also recently fallen far off the previous trend.

6 It’s hard not to be excited by the prospect of all of the lives saved by getting distractible humans out of the business of driving, not to mention the reduction in traffic jams coming from the more consistent spacing and speed of autonomous vehicles, or the lives that will be transformed by the reduced expense and hassle of getting from place to place. But there are 3.5 million professional truck drivers in the US along with perhaps half a million or so taxi drivers, chauffeurs, and ride-sharing drivers. That’s a lot of generally lower-skilled people who will need to find other work.

7 It is worth noting that part of Trump’s proposed fiscal stimulus – infrastructure spending – is the same medicine that Larry Summers suggests would be most helpful in ending secular stagnation. In Summers’ reading of the economy, our problem is too much savings and too little investment. Government borrowing to spend directly on infrastructure therefore gives a twofer of lower aggregate savings and higher investment. The other part of Trump’s proposed stimulus, however, is tax cuts, and this would not be particularly helpful if Summers is right. Some portion of the tax cuts would be saved (particularly if the rich get a big chunk of the savings), reducing the effect on that side, and the rest would be generally consumed. While this consumption would cause some knock-on investment as capacity utilization rises, it seems unlikely that this would be a particularly large fraction of the total.Disclaimer: The views expressed are the views of Ben Inker through the period ending January 2017, and are subject to change at any time based on market and other conditions. This is not an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security and should not be construed as such. References to specific securities and issuers are for illustrative purposes only and are not intended to be, and should not be interpreted as, recommendations to purchase or sell such securities.

8 While this correlation exists, I don’t believe it is meaningful. There have been very few “events” in which tax rates changed meaningfully, so there hasn’t been a lot for the correlation to sink its teeth into. Suffice it to say, there isn’t a lot of historical evidence that falling tax rates increased after-tax profits.

9 This should be true in a competitive market. Monopolies may work differently, although even there one would not expect the monopolist to capture all of the tax decrease. Expect more on that topic in an upcoming quarterly.

Copyright © GMO LLC