by Corey Hoffstein, NewFound Research

Summary

- In a persistent, low interest rate environment, dividend strategies have rapidly increased in popularity.

- In theory, investors should be indifferent to dividends. In practice, they are not.

- As a strategy, a focus on high dividend yield may simply be a (poor) value strategy in drag.

- A focus on dividend payers and growers may give investors the ability to tap into the reinvestment premium and create a quality tilt in their portfolio.

As low-to-negative interest rates plague yield-seeking investors, dividend-based strategies have continued to grow in popularity.

At face value, swapping cash flow from a bond for that from a diversified stock index does not seem like all that horrible of an idea. Yields are higher, have historically been incredibly stable, and have the potential to grow over time. Plus, in the U.S., qualified dividends are taxed at a substantially lower rate than the cash flow from bonds, which is important in taxable accounts.

Yet even this seemingly vanilla investment strategy has its critics. And not just because of the higher principal risk relative to high quality bond portfolios.

A Bit of Terminology

Before we dive in, we want to outline the three primary types of dividend strategies we will be discussing in this commentary.

- Dividend Payers: Invest in companies that pay a dividend; avoid those that do not.

- Dividend Growers: Invest in companies that consistently increase their dividends; avoid those that cut or eliminate their dividends.

- High Yielders: Invest in the highest yielding group of stocks; avoid the lowest yielding group.

There are, of course, tilts that exist as well (e.g. quality dividend payers or low volatility dividend payers), but we’re going to ignore those variations in this commentary.

The General Case For Dividend Investing

Ignoring the specific implementations for a moment, there are a number of reasons why dividends may be attractive to investors.

- They are an important part of total return. In Dividends and the Three Dwarfs (Financial Analysts Journal, 2003), Rob Arnott demonstrates that of the 7.9% annualized total return of U.S. stocks from 1802 to 2000, 5.0% came from dividends. To quote the paper, “Dividends not only dwarf inflation, growth, and changing valuation levels individually, but they also dwarf the combined importance of inflation, growth, and changing valuation levels.” Here at Newfound, using data from the Shiller Data Library, we calculate that from 1881 to 2015, nearly 50% of total nominal U.S. equity returns and nearly 70% of total real U.S. equity returns have come from dividends.

- The ability to pay a dividend consistently may serve as an effective proxy for company health or quality.

- Dividend growth has historically been significantly more stable than earnings growth or equity price growth. A working paper from Reality Shares, titled A possible pathway to low correlation and low volatility: isolating dividend growth, reports the annualized volatility of S&P 500 dividends as 3.1% from 1971-2016, in comparison to 12.9% for S&P 500 earnings or 15.2% for S&P 500 price.

- Dividend growth has historically been a diversifier to inflation and rising interest rates.

- In the U.S., qualified dividends are currently a tax-advantaged form of income in comparison to interest from bonds.

Empirical Evidence & Studies Supporting Dividend Strategies

There are a number of academic studies supporting the efficacy of all three types of dividend strategies.

Dividend Payers

- In Dividends: A Review of Historical Returns, Heartland Advisors reports that from the period of 1928 to 2015:

- The annualized return of non-dividend payers is significantly below (about 50 basis points) even the lowest quintile of dividend payers.

- Non-payers had a significantly higher annualized standard deviation compared to payers (approximately 10 percentage points higher).

- Non-payers had significantly worse average performance during market corrections.

Dividend Growers

- Reality Shares reports that from 1972-2016, Dividend Growers & Initiators have returned 9.84% annualized, while No-Change Payers have returned 7.26%, Non-Payers returned 2.34%, and Cutters & Eliminators returned -0.55% (all returns annualized).

- In An Economic Perspective on Dividends, Santa Barbara Asset Management reports that:

- Dividend Growers & Initiators have not only historically offered higher annualized returns with less risk (1972 – 2015), but also have outperformed No-Change Payers, Non-Payers, and Cutters & Eliminators over 100% of rolling 15-year periods (1987 – 2015).

- In both domestic and international markets, dividend growth has been the largest component of total annualized return (1970 – 2015).

High Yielders

- In The Future for Investors, Jeremy Siegel found that from 1957 to 2002, the highest quintile of dividend yielders outperformed the S&P 500 by 309 basis points a year and the lowest quintile of dividend yielders by 477 basis points a year.

- In The Importance of Dividend Yields in Country Selection, Michael Keppler found that when countries’ equity markets were ranked by their dividend yield, the highest yielding countries outperformed the lowest yielding countries by 1280 basis points per year from 1969 – 1989.

- In Stocks, Bonds, and the Efficacy of Global Dividends, O’Shaughnessy Asset Management finds that the highest decile of global dividend payers outperforms the MSCI by 570 basis points a year from 1970 – 2010.

So what is there not to like?

The Theoretical Case Against Dividend Strategies

Despite the plethora of empirical evidence, in theory, investors should be indifferent as to whether free cash flow is paid out via dividends or reinvested in the company. This theory is rooted in the Modigliani-Miller theorem. We can understand this concept from both the company’s perspective and the investor’s perspective. From the company’s perspective, dividend increases and/or decreases can be achieved by adjusting the firm’s capital structure, without impacting overall firm value. For example, an increase in the dividend could be financed by issuing new shares. This issuance would dilute existing shareholders. However, this capital loss would be exactly offset by the increased dividend return.

From the stockholder’s perspective, dividend preferences can be achieved through simple portfolio transations. Let’s say a company increases its dividend yield from 2.5% to 5.0%, but the investor only wants 2.5%. He can simply re-invest the extra 2.5% into the company, leaving himself with the same outcome as if the company had never increased the dividend in the first place.

It is important to note that the theory does rely on several assumptions that may not hold in the real world, including no taxes and that investors and managers have access to the same information. Nevertheless, given that stock prices drop on the ex-date by the value of the dividend paid, at a basic level dividends paid should not affect an investor’s net worth.

The Case Against High Dividend Yield: Just a Poor Value Proxy?

One of the specific arguments against high yield stocks is that they are just a poor proxy for value investing. Consider that under some general assumptions, yield can be a proxy for common valuation metrics like book-to-market and price-to-earnings:

- Using the dividend discount model, we can assume book (e.g. “fair”) value is equal to the net present value of future dividends. With a constant growth rate of dividends (g) and constant cost of capital (r), book value per share should be proportional to the current annual dividend per share (D), or, equivalently, book-to-market should be proportional to dividend yield.

- Similarly, if we assume a constant long-term payout ratio (p), dividends per share (D) are proportional to earnings per share (E). This makes yield inversely proportional to price-to-earnings (or proportional to earnings yield).

In Dividend Investing: A Value Tilt in Disguise?, Gregg Fisher found, as have many other papers, that high dividend yielders significantly outperform the broad market. However, when returns of the portfolio are decomposed into the factors that explain returns, value (price-to-book) and earnings yield (earnings-to-price) were significant contributors. After accounting for these factors, the contribution of dividend yield (dividend-to-price) was actually negative.

Potential problems with using high yield as a value proxy are:

- High dividend yield may also imply poor growth prospects.

- The strategy will avoid profitable companies that have temporarily suspended or reduced dividends.

- Income-focused investors may structurally prevent high dividend yield companies from becoming as undervalued as lower-yielders or non-payers.

- High yielders are, on average, larger than their counterparts in value portfolios, creating a negative size effect.

Quantitatively, in High Yield, Low Payout, Credit Suisse reports that the highest decile of dividend yielders actually underperforms the 8th and 9th deciles. This may be a potential indication that high dividend yield, on its own, may be an inefficient measure.

One potential remedy for investors still seeking higher yields may be to tilt for quality.

- In High Yield, Low Payout, Credit Suisse finds that selecting high dividend yield companies with low payout ratios significantly outperformed other variants.

- In The Market for “Lemons”: A Lesson for Dividend Investors, Research Affiliates finds that screening for quality filters such as return on assets, growth in net operating assets, and debt coverage ration can help investors differentiate high, sustainable dividend opportunities and lemons.

Dividend Payers: A Bird in the Hand is Worth Two in the Bush

As mentioned above, theory – albeit a theory that may rely on imperfect assumptions about the market - holds that investors should be indifferent to whether dividends are paid or not. Reality may be more nuanced.

Between dividend and reinvestment, there exists a great gulf of uncertainty. A dividend today is, quite simply, not the same as a potential future return: particularly when evidence suggests that companies have historically done a terrific job of destroying reinvested capital.

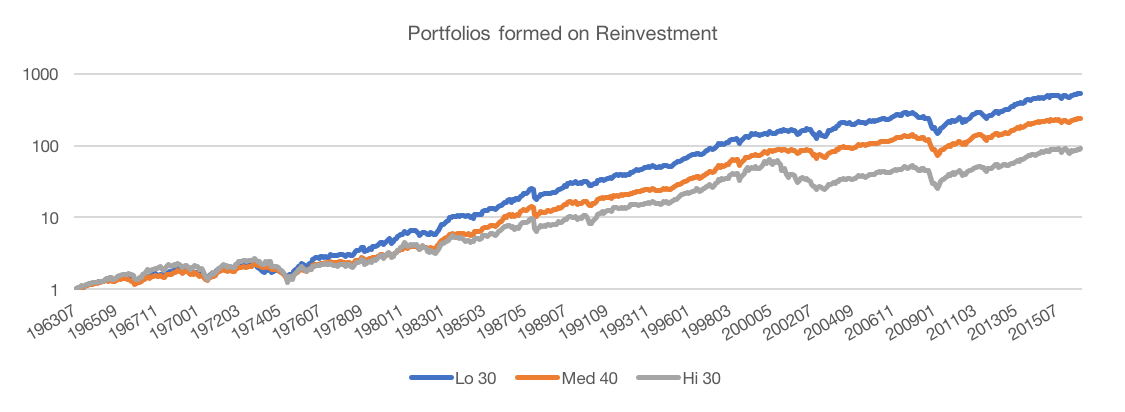

Consider that companies with a high reinvestment rate have lower returns than those with a lower reinvestment rate.

Source: Kenneth French Data Library. Calculations by Newfound Research. Past performance is not a guarantee of future returns.

To us, the above chart is striking. Companies are generally not good at reinvesting free cash flow.

Given that a dividend is explicitly capital not reinvested, focusing on consistent dividend payers may be a way to access the premium found in companies with low reinvestment rates.

In Surprise! Higher Dividends = Higher Earnings Growth, Robert Arnott and Cliff Asness come to a similar conclusion. Regressing current dividend payout ratio against subsequent 10-year earnings over the period of 1946-1991, they find that when current payout ratios are high (i.e. a large percentage of current earnings is paid out as a dividend), forward earnings growth is high. This is the exact opposite of what we would expect, indicating that earnings retention and reinvestment actually destroys capital.

Dividend Growers as a Quality Proxy

In the last section, we demonstrated how companies that pay dividends may offer outperformance opportunities because they avoid reinvestment in low growth opportunities. A focus on not only a consistent dividend-payout policy, but a dividend growth policy may further drive business managers toward create strong, stable companies.

There is a cultural pressure against corporate executives cutting dividends. In Distribution of Incomes of Corporations Among Dividends, Retained Earnings, and Taxes, John Lintner found that dividends are highly sticky, with corporate managers loathe to cut them. Therefore, a portfolio of consistent growers may be comprised of companies built to weather future economic storms.

Furthermore, in What Do Dividends Tell Us About Earnings Quality?, Douglas Skinner and Eugene Soltes find that reported earnings of dividend-paying firms are more persistent than those of other firms. In other words, dividends provide information about the sustainability of earnings.

A focus, specifically, on persistent dividend growers may allow investors to tap into companies with higher earnings sustainability, less wasteful reinvestment, and more predictable total return.

A Quick Note on Dividend Growth Portfolios

We are big believers in outcome-oriented investing for many reasons. Chief among these reasons is that outcome-oriented strategies can help investors stay on track by making it easier to set appropriate expectations. With dividend growth strategies, the expectations are simple: a steadily growing stream of dividend income. As long as this objective continues to be achieved over reasonable time horizons, clients can be appropriately counseled to ignore account fluctuations.

Of course, we know that is no guarantee that any strategy can grow dividends year-after-year with no interuptions, especially during market panics. For example, even the S&P 500 Dividend Aristocrat Index, which has grown dividends at a 6%+ annual rate over the last nine years, saw annual dividends collectively decline by 8.5% from 2008 to 2009. We can easily set expectations around these types of events, explaining that temporary declines in dividends may occur when market-wide stress ensues.

What might be more surprising – and may lead to more stress as it can be very hard to set expecations around this type of surprise - is that strategy rebalancing rules, especially those that introduce significant turnover, can cause total portfolio dividends to decline even when individual component companies all increase their dividends over the same time period. As a result, we prefer simplistic dividend growth models that are relatively low turnover to approaches that may introduce secondary critiria (e.g. low volatility) which could increase turnover.

The Conservation of Risk

At Newfound, we believe in the conservation of risk: that risk cannot be destroyed, only transformed.

When investing in a dividend stock portfolio, there are a number of risks that investors may potentially be adding to their portfolio that they should be aware of.

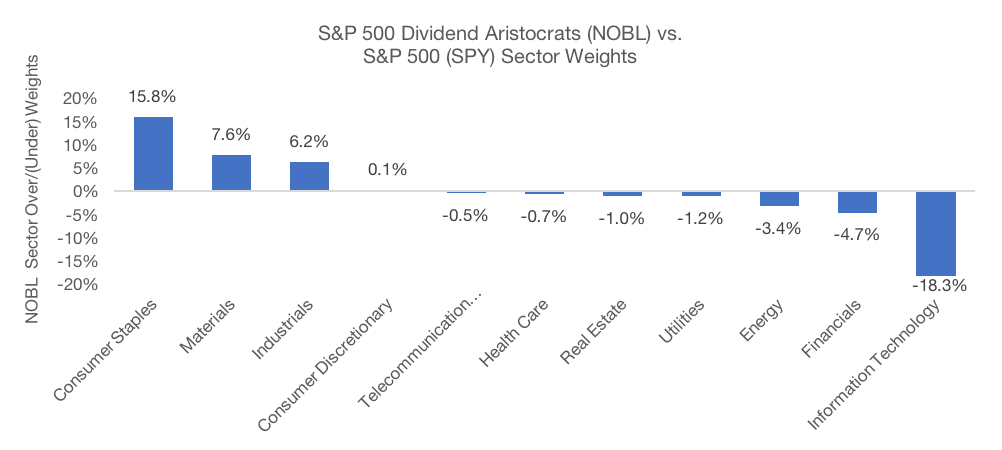

- Implicit sector bets: Certain sectors are more likely to pay dividends than others. A focus on dividend payers may lead to higher implicit sector bets. Furthermore, the stricter portfolio inclusion criteria become (e.g. 25-year dividend growers vs. 10-year dividend growers), the larger these implicit bets can get.

Source: ProShares and SPDR. Calculations by Newfound Research. - Dividends are not legally binding: Unlike bonds, there are no legal repurcussions for defaulting on dividend payments. For investors seeking to offset cash-flow liabilities with income, cash dividends may represent a higher risk than bond income. That being said, there are consequences for cutting dividends (e.g. exclusion from portfolios that represent significant invested capital and may depress share prices).

- Tax risk: Historically, dividends were taxed at a higher rate. It was not until 2003 that qualified dividends received preferential tax treatment. Dividend-focused investors bear the risk that this tax policy may change.

Conclusion

Even a fairly vanilla investment strategy, like dividend investing, is not without its critics. There is a significant amount of evidence that dividend strategies – including focusing on dividend payers, dividend growers, or high yielding stocks – have historically generated excess return.

In our opinion, the most valid strategy critique is that a focus on high yielders is really just a value strategy in drag: and a poor one at that. Empirical evidence suggests that portfolios built from high yielding stocks have high loadings on traditional valuation metrics and that the dividend yield factor is actually a drag on returns. It is no surprise then that these portfolios typically lag traditionally built value portfolios. Investors focused on long-term growth could likely do better than high yield dividend portfolios.

Nevertheless, dividends may play an important role in helping investors avoid destructive reinvestment by company managers. So a focus on dividend payers may help investors capture the reinvestment premium. A focus on dividend growers may allow investors not only to tap into this premium, but do so with higher quality companies.

Client Talking Points

- Dividends have been the largest contributor to long-term total returns in the U.S. stock market.

- While high dividend yield may be attractive from an income perspective, in reality it has proven to be a bad value strategy. If we’re interested in long-term total return, we should focus on traditional value measures.

- A focus on dividend payers and growers may allow us to tap into higher quality companies that avoid bad reinvestment practices.

Copyright © NewFound Research