by Cullen Roche, Pragmatic Capitalism

There were many dire predictions about the stock market in the wake of Donald Trump’s victory. These predictions even looked credible in the moments after his win when the S&P 500 immediately collapsed 5% on the evening of the election. Then, miraculously, the S&P 500 bounced right back and is up about 2% since election day. Global stocks haven’t budged much in the aggregate and emerging market stocks are actually down almost 10% over the same period. So, depending on where you live in the world and what you define as “the stock market”, these predictions could have been right or could have been wrong.

In the wake of this result there has been a harsh backlash against anyone who tries to forecast just about anything. Some people, like Barry Ritholtz, even say that this proves we don’t “know anything” and that “forecasters are terrible”. Such comments are probably true to some degree, but they’re demonstrably false as well. After all, the real lesson from the market’s reaction to the election is not that forecasting is stupid or that no one knows anything. The real lesson is:

- No one know what stocks will do in the short-term.

- Good forecasters think in terms of probabilities.

Predicting the results of corporate America based on a short-term event is a fool’s errand. Stocks generate long-term returns based on how underlying corporations perform at a fundamental level. Stocks generate their short-term returns based on how behaviorally biased buyers and sellers react and overreact to any multitude of events. But the fact that stocks are difficult to predict in the short-term does not mean no one can make forecasts about the markets or that no one knows anything. And the data confirms this.

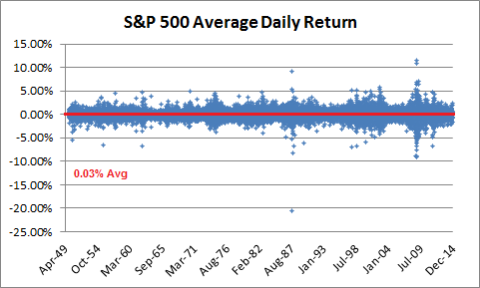

As I’ve shown before, increasing your time horizon in the stock market substantially increases your odds of making accurate forecasts.¹ In the very short-term, the stock market is almost entirely random with daily fluctuations averaging just 0.03%:

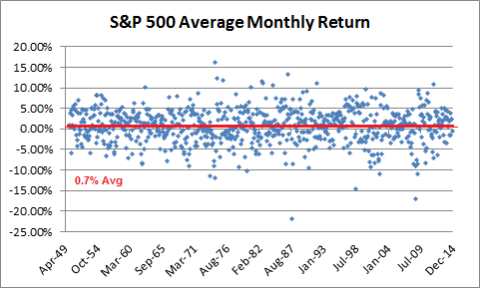

On a monthly basis the average return skews marginally positive to 0.7%, but still appears to be largely random:

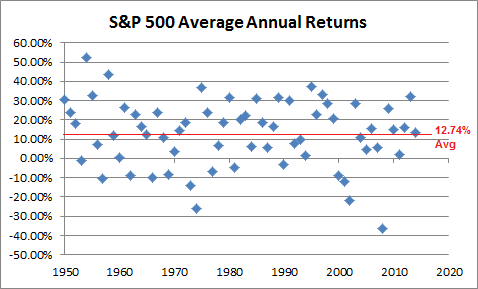

Over an annual basis the average return jumps significantly to almost 13%. The returns still appear somewhat random, but they have a significant positive skew:

Increasing your time horizon reduces the randomness of the stock market’s negative performance because you’re improving the odds that your portfolio’s performance will correlate with broader corporate output. Since corporations tend to pay out positive cash flows over the long-term stock valuations tend to reflect this over the long-term. It’s not much different than trying to predict the long-term performance of a 10 year T-Bond. The fool tries to predict what that bond will do on any given day, but the intelligent asset allocator knows, for a fact, that there is a high probability of positive future cash flows if that instrument is held for its entire 10 year time horizon. By increasing your time horizon you remove the manic overreactions of guessers trying to predict the market’s moves and instead correlate your returns more closely with the way that actual businesses pay out their cash flows over the long-term. As I’ve noted before, asset allocation is really all about asset and liability mismatch and financial success is largely contingent on your ability to understand the temporal mismatch between those assets and liabilities.²

The intelligent asset allocator doesn’t shun forecasts or assume that no one knows anything. Instead, they can apply a more rigorous empirical approach that takes advantage of the high probabilities of certain events occurring across a realistic time horizon. I might not know what the stock market will do today, tomorrow or next year, but I know that the instrument is a fundamentally long-term instrument that will have a high probability of paying out positive future cash flows if I hold it for a long enough time horizon. When blended with the proper mix of other financial assets I can make high probability forecasts about my likelihood of generating positive overall cash flows across specific time horizons.

So, the lesson from the Trump election is very simple:

- The short-term is really damn difficult to predict in the stock market and those who fall victim to short-termism will substantially reduce their probability of financial success in the long-term.

¹ – Great investors think in terms of probabilities.

² – Overcoming the Problem of Short-Termism.

Copyright © Pragmatic Capitalism