by Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense

The value premium has been talked about in investment circles going all the way back to the 1934 release of Benjamin Graham’s Security Analysis. At its core value investing relies on buying undervalued securities, something every investor can or should be able to intuitively understand.

You buy stocks for less than their fundamental value, wait until that value is recognized by the market, profit, then rinse and repeat until you’re rich. Sounds easy enough until you try it in practice and realize that cheap securities can always get cheaper and the market is not always accommodating in how and when it recognizes value over time. It’s the old line that value investing is simple, but never easy.

Although value investing is as old as the hills, many investors are wondering if it’s getting too crowded.

This argument does have some validity. There’s more competition than ever in today’s markets. You can access value strategies through mutual funds, smart beta funds and ETFs that would have been cost prohibitive in the past. There are also hundreds and hundreds of quantitative hedge funds using algorithms to scour the markets for beaten down shares with attractive valuations.

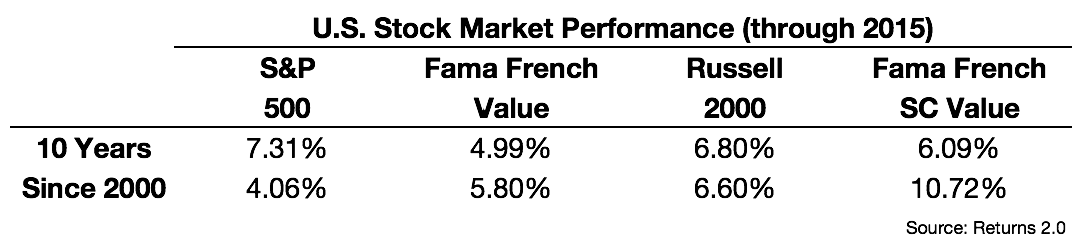

The last decade or so hasn’t been too kind to value investors using one of the first academic definitions courtesy of Fama and French data:

Value strategies outperformed during the 2000-2002 bear market so the numbers since the turn of the century are still pretty good but the past 10 years have seen both large and small cap value strategies underperformed the overall market.

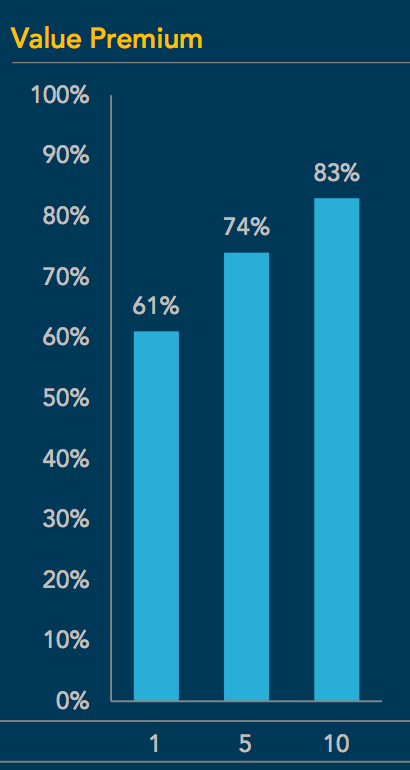

If you look at the historical data on the value premium it would make sense that it shows periods of underperformance. Value doesn’t always work, because nothing does, but it has worked most of the time with data going back to the 1920s (via DFA):

You have to remember that what “works” in investing is a subjective term. It doesn’t mean always and forever. It’s quite possible that these win rates will go down in the future, but I always say that the hardest question to answer as an investor is this: is my strategy doing poorly because it doesn’t work anymore or should I be patient and wait it out?

No one ever knows the answer to this question with any certainty, but in this instance there is another way to check whether or not value investing is broken or just going through an inevitable period of poor relative performance.

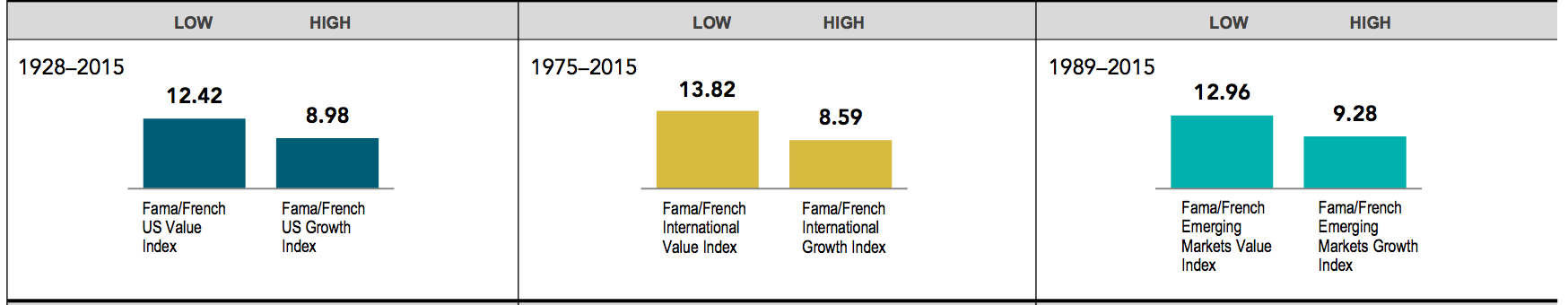

The term quants use to tell if a factor or strategy has legs is ‘robust.’ For a factor to be considered robust you would generally like to see it work in a number of different assets, geographies and securities for proof of concept. Here you can see this same value factor applied across foreign developed and emerging market stocks:

Value investing has worked well historically in both over time, just as it has in the U.S.

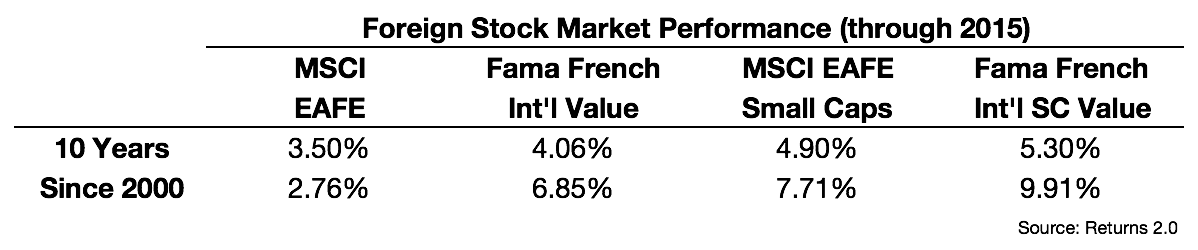

Now here are the same time frames we used above for foreign stocks:

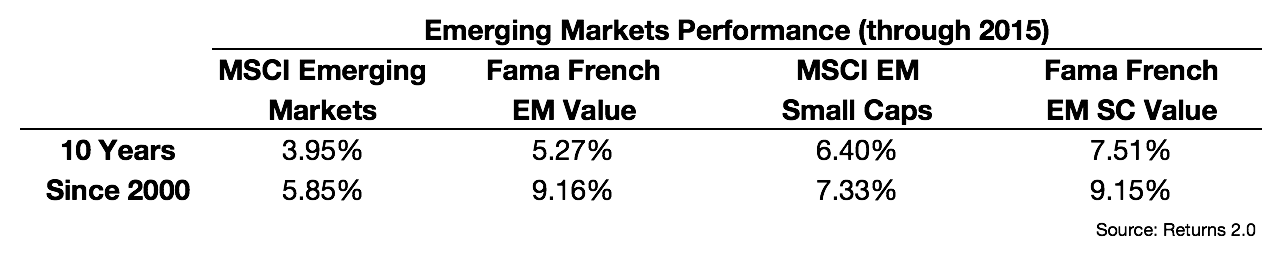

And emerging markets:

So while the value premium has been severely lacking in the U.S. over the past decade, it is still very much alive in foreign and emerging market stocks. It’s also interesting to note that even though the small cap premium has been absent over the past 10 years in the U.S., smaller stocks have outperformed in both international developed and emerging markets.

So it does not appear that the value premium is disappearing everywhere.

Does it make sense that the value premium should shrink going forward when compared to past levels?

Certainly. Investors have known about value investing for decades, but the rise of smart beta products and the increased collective knowledge base of the investing community would suggest that the 3+% annual premium should be a thing of the past.

Does that mean the value premium will completely disappear in the future?

No one knows the answer to this question. It could definitely become too crowded at times as investors chase performance following a good multi-year run. Yet investors will always have an infatuation with glamour growth stocks with a compelling narrative. It’s never going to be easy to buy what’s been performing terribly lately. Those things won’t go away.

If nothing else, the value factor can provide valuable diversification benefits when used across a wide range of markets. For those who are unwilling to diversify among factors you have to plan on being very patient. Underperformance over decade-long periods should be expected.

Further Reading:

What Happens When the Umbrella Shop Gets Too Crowded?