The Stock Market’s CAPE

|

| Shiller CAPE data (from his site) |

The CAPE’s Weakest Links

|

| Download spreadsheet with PE ratios |

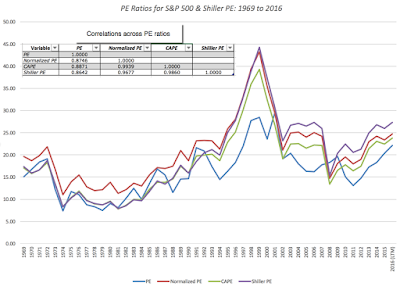

First, it is true that especially after boom periods (where earnings peak) or economic crises (where trailing earnings collapse), the CAPEs (both mine and Shiller's) yield different numbers than PE. Second, and more important, the four measures move together most of the time, with the correlation matrix shown in the figure. Note that the correlation is close to one between the normalized PE and the CAPE, suggesting that the inflation adjustment does little or nothing in markets like the US and even the normalization makes only a marginal difference with a correlation of 0.86 between the unadjusted PE and the Shiller PE.

2. The CAPE is not that predictive

As a follow-up, I ran a simple test of the payoff to market timing, using the Shiller CAPE and actual stock returns from 1927 to 2016. At the start of every year, I first computed the median value of the Shiller CAPE over the previous fifty years and assumed an over priced threshold at 25% above the median (which you can change). If the actual CAPE was higher than the threshold, I assumed that you put all your money in treasury bills for the following year and that if the CAPE was lower than the threshold, that you invested all your money in equities. (You can alter these values as well). I computed how much $100 invested in the market in 1927 would have been worth in August of 2016, with and without the market timing based on the CAPE:

|

| Download spreadsheet and change parameters |

Note that as you trust CAPE more and more (using lower thresholds and adjusting your equity allocation more), you do more and more damage to the end-value of your portfolio. The bottom line is that it is tough to get a payoff from market timing, even when the pricing metric that you are using comes with impeccable credentials.

3. Investing is relative, not absolute

|

| Download T Bond Rate PE data |

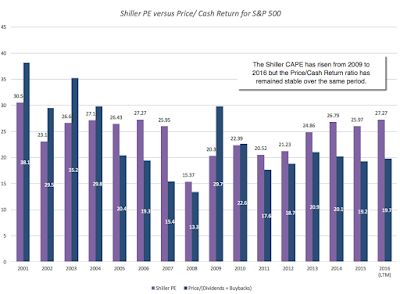

4. Its cash flow, not earnings that drives stocks

- The Treasury Alternative (or how much are you afraid of your central bank?) If the reason that you are in stocks is because the payoff for being in bonds is low, that equation could change if the bond payoff improves. If you are Fed-watcher, convinced that central banks are all-powerful arbiters of interest rates, your nightmares almost always will be related to a meeting of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), and in those nightmares, the Fed will raise rates from 1.50% to 4% on a whim, destroying your entire basis for investing in stocks. As I have noted in these earlier posts, where I have characterized the Fed as the Wizard of Oz and argued that low rates are more a reflection of low inflation and anemic growth than the result of quantitative easing, I believe that any substantial rate rises will have to come from shifts in fundamentals, either an increase in inflation or a surge in real growth. Both of these fundamentals will play out in earnings as well, pushing up earnings growth and making the stock market effect ambiguous. In fact, I can see a scenario where strong economic growth pushes T. bond rates up to 3% or higher and stock markets actually increase as rates go up.

- The Earnings Hangover It is true that we saw a long stint of earnings improvement after the 2008 crisis and that the stronger dollar and a weaker global economy are starting to crimp earnings levels and growth. Earnings on the S&P 500 dropped in 2015 by 11.08% and are on a pathway to decline again this year and if the rate of decline accelerates, this could put stocks at risk. That said, you could make the case that the earnings decline has been surprisingly muted, given multiple crises, and that there is no reason to fear a fall off the cliff. No matter what your views, though, this will be more likely to be a slow-motion correction, offering chances for investors to get off the stock market ride, if they so desire.

- Cash flow Sustainability: My biggest concern, which I voiced at the start of the year, and continue to worry about is the sustainability of cash flows. Put bluntly, US companies cannot keep returning cash at the rate at which they are today and the table below provides the reason why:

| Year | Earnings | Dividends | Dividends + Buybacks | Dividend Payout | Cash Payout |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 38.85 | 15.74 | 30.08 | 40.52% | 77.43% |

| 2002 | 46.04 | 16.08 | 29.83 | 34.93% | 64.78% |

| 2003 | 54.69 | 17.88 | 31.58 | 32.69% | 57.74% |

| 2004 | 67.68 | 19.407 | 40.60 | 28.67% | 59.99% |

| 2005 | 76.45 | 22.38 | 61.17 | 29.27% | 80.01% |

| 2006 | 87.72 | 25.05 | 73.16 | 28.56% | 83.40% |

| 2007 | 82.54 | 27.73 | 95.36 | 33.60% | 115.53% |

| 2008 | 49.51 | 28.05 | 67.52 | 56.66% | 136.37% |

| 2009 | 56.86 | 22.31 | 37.43 | 39.24% | 65.82% |

| 2010 | 83.77 | 23.12 | 55.53 | 27.60% | 66.28% |

| 2011 | 96.44 | 26.02 | 71.28 | 26.98% | 73.91% |

| 2012 | 96.82 | 30.44 | 75.90 | 31.44% | 78.39% |

| 2013 | 107.3 | 36.28 | 88.13 | 33.81% | 82.13% |

| 2014 | 113.01 | 39.44 | 101.98 | 34.90% | 90.24% |

| 2015 | 100.48 | 43.16 | 106.10 | 42.95% | 105.59% |

| 2016 (LTM) | 98.61 | 43.88 | 110.62 | 44.50% | 112.18% |

In 2015, companies in the S&P 500 collectively returned 105.59% of their earnings as cash flows. While this would not be surprising in a recession year, where earnings are depressed, it is strikingly high in a good earnings year. Through the first two quarters of 2016, companies have continued the torrid pace of buybacks, with the percent of cash returned rising to 112.18%. The debate about whether these buybacks make sense or not will have to be reserved for another post, but what is not debatable is this. Unless earnings show a dramatic growth (and there is no reason to believe that they will), companies will start revving down (or be forced to) their buyback engines and that will put the market under pressure. (For those of you who track my implied equity risk premium estimates, it was this concern about cash flow sustainability that led me to add the option of allowing cash flow payouts to adjust to sustainable levels in the long term).

The Market Timing Mirage

YouTube

Datasets