Who wants pie?

by Scott Brown. Ph.D., Chief Economist, Raymond James

May 2 – May 6, 2016

“We ought to make the pie higher.” – George W. Bush

Productivity growth is perhaps the single most important factor in the economy. Increased output per worker facilitates improvements in the standard of living over time. It’s how our children have a better future. It also helps support corporate profits. What to make then of the current situation, where productivity growth has slowed to a crawl in the U.S. and around the world? Will there be enough pie to go around?

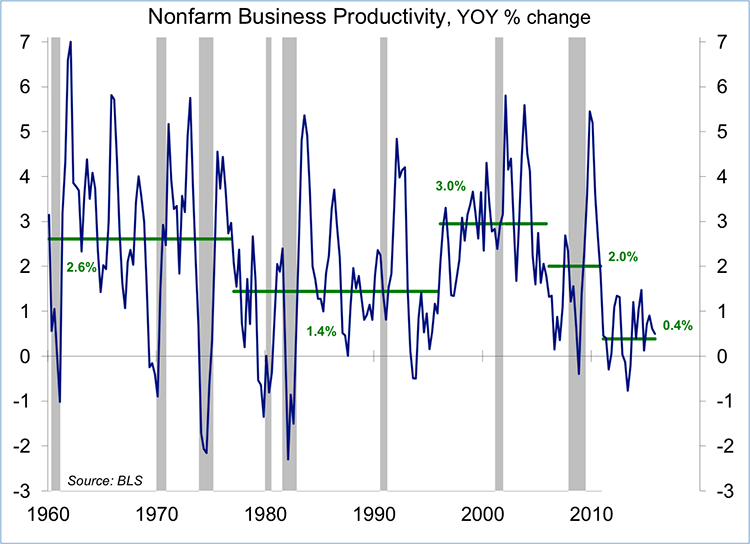

As a statistic, productivity is quirky. Those who have studied the hard sciences know that when you start multiplying and dividing statistical estimates, the uncertainty can get unruly. Productivity is nominal output, divided by a price measure, then divided by a labor input measure – each is estimated. As a consequence, quarterly productivity figures are choppy and subject to large revisions. Given all that, the trend in recent years has been unusually weak. Figures are somewhat better for the nonfinancial corporate sector, but still slower.

[Tweet "Will there be enough pie to go around?"]Economists had long puzzled over the slowdown in productivity growth from the late 1970s to the early 1990s. Nobel Laureate Robert Solow said, during that time, that computers were everywhere in the economy except in the productivity figures. Scanners and inventory management software were just getting going in the early 1980s, but took some time to perfect (you’re welcome, Amazon and Walmart). In the late 1990s along came cell phones, networking equipment, and the Internet. Productivity surged, first in the production of these technologies, then in their application. Firms discovered they could do more with fewer workers and the early 2000s. It was not just a jobless recovery, but a “job loss” recovery. Productivity growth after the Great Recession has been anemic, likely because of weaker (productivity boosting) capital spending in the early part of the recovery.

The slowdown in productivity growth is a puzzle. No one seems to know the exact cause, but there are theories. As noted, weaker business fixed investment was a likely factor. Some have suggested that this is really a measurement issue. Real GDP is likely a lot stronger because it doesn’t properly account for the fact that I have dictionaries, encyclopedias, maps, restaurant and film reviews, and so on in the palm of my hand. Others argue that productivity is lower because people are watching cat videos instead of working.

If the issue is capital investment, that may take care of itself over time (as long as capital investment picks up). If it’s more permanent, then the longer-term outlook is more troublesome.

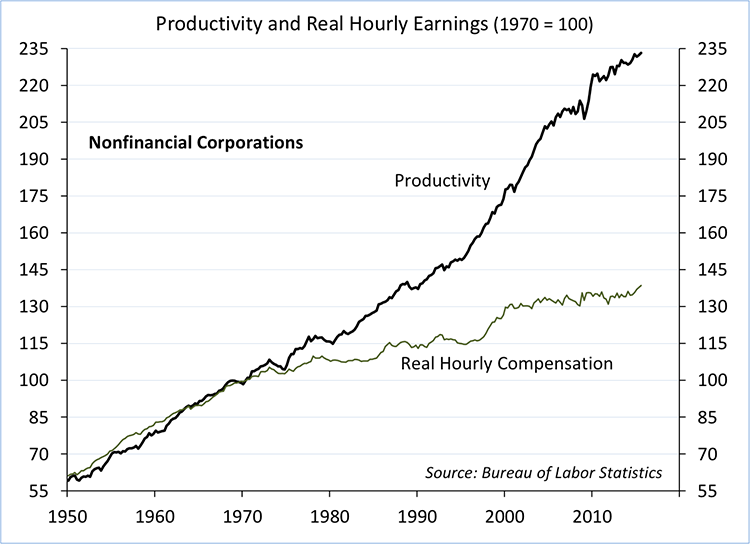

In the 1950s and 60s, real wage growth rose in line with productivity. Since the early 1970s, most (not all) of the growth in productivity has gone to profits. What will then happen if the slower trend of productivity growth is more permanent? Much will depend on the amount of slack in the labor force. If the job market tightens, labor could take a larger share of a smaller pie (actually a more slowly growing pie).

California and New York are now in the process of raising their minimum wages to $15 per hour (over five years in CA, steeper but strangely inconsistent across NY). Many will argue whether this is good or bad. Typically, minimum wage increases aren’t all that important (it’s usually very low to begin with and you rarely see much impact on employment, or poverty for that matter). Yet, California will be more of an experiment. Going from $10 to $15 is a large increase as far as minimum wages go.

Waitress, a new musical opened on Broadway last week. Before the play begins, someone actually bakes a pie, so the smell wafts through the theatre during the play. To enhance the aroma, the recipe is altered. The result smells great, but tastes “wrong.” Yet, that doesn’t stop the stage hands from eating it.

Copyright © Raymond James