Why Bonds Are So Confusing

by Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense

The Wall Street Journal shared the results of a survey which shows many investors don’t understand how bond math works:

Despite the massive growth of the bond market in recent years, many individual investors are still fuzzy on their bond math.

A recent survey conducted for BNY Mellon Investment Management found that 40% of individual investors don’t know bond prices fall when interest rates rise, and vice versa. It’s a central tenet of bond investing that helps explain why everyone in the bond world is so focused on when and by how much central banks like the Federal Reserve adjust benchmark interest rates.

Bonds are much more formulaic than stocks. Long-term returns tend to track the beginning interest rate. When rates rise, the price of a bond falls. When rates fall, the price of a bond rises. There are some minor intricacies including convexity that come into play, but for the most part bonds and rates have a simple inverse relationship.

Here’s an example. Let’s say the current market interest rate is 5% and that’s the yield on the bonds you hold. Then the market rates go up to 7% so new bonds now pay that higher yield. But you’re still holding a bond that only pays 5% so no one is going pay you 100 cents on the dollar for it when they can earn 2% more with a newer security. The price of existing bonds has to fall to bring them in line with the overall yield of the now higher-yielding market interest rates. When rates fall your bond is worth more because market yields are lower than the bond you hold.

Even those investors who do understand bond math often misinterpret what this really means since this is from the standpoint of prices and principal value. It doesn’t consider total return. Yes, if interest rates rise a substantial amount in a short period of time investors will see losses in their bond holdings. But these losses are temporary when we’re dealing with high quality bonds. And rising interest rates doesn’t have to lead to losses in bonds. It all depends on the starting yield and the magnitude of the rate rise.

My favorite example of this is the rising rate period from 1950-1981. Rates went from 2.32% all the way up to 15.32% on the 10 Year Treasury. Returns, however, were not as bad as you would think:

Rates went sky high but returns were still positive every single decade. They weren’t great, but they were still positive from a nominal perspective. It was only after accounting for inflation that bonds showed real losses in this time and most of that was from the 1970s.

The 1950s scenario makes the most sense if you’re looking for a parallel to today’s markets. Interest rates doubled over the course of the decade and 10 Year Treasury returns were down every other year. Those losses were fairly subdued (-0.30%, -1.34%, -2.26%, -2.10% and -2.65%) as a bad year in the bond market is like a bad day in the stock market.

This is one of the reasons that average investors (and let’s be real, many professionals) are so confused about the mechanics of bonds. Yes, rising interest rates means lower bond prices. But it doesn’t necessarily mean lower bond total returns. Remember, to earn better long-term returns in bonds we need to see higher interest rates eventually. When yields rise you start to earn more income. That’s a good thing.

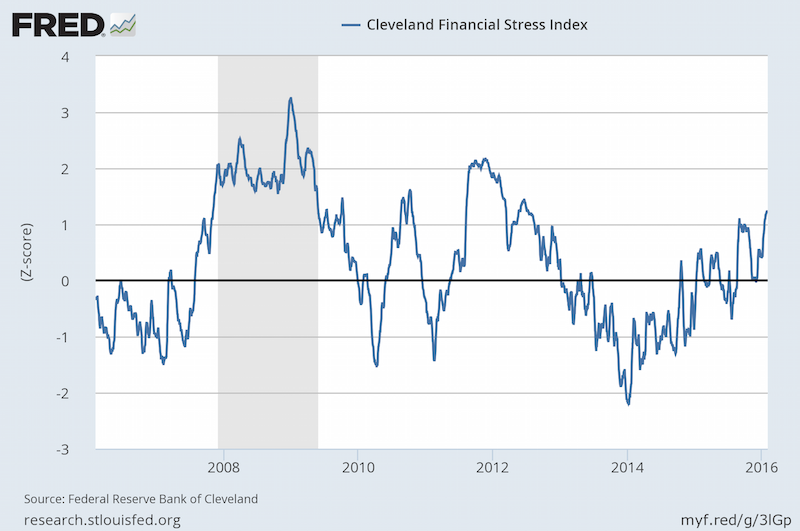

Of course, investors have been nervous about rising rates for some time now and it just hasn’t happened. Even after the Fed raised the Fed Funds Rate in mid-December, market interest rates have continued to fall. Who knows when rates will rise. When they do, investors have to remember that there will likely be some short-term losses. But bonds still pay out their income and mature at par value. From a total return perspective this means it won’t be as bad as some would have you believe (as long as we don’t see negative rates).

Source:

Many Investors Are Still in the Dark About Bonds (WSJ)

Further Reading:

The Most Interesting Asset Class Over the Next Decade

Copyright © A Wealth of Common Sense