Understanding the Two Chinas

by Fixed Income AllianceBernstein

Our view that China may be heading for a mild cyclical upswing next year needs to be set against the background of the broader economy, which is changing rapidly. We think that it makes sense to view the economy as consisting of two parts: old and new.

In its latest Five-Year Plan—full details of which will be announced in March 2016—the Communist Party of China set its goal for annual economic growth at 6.5%, well below the double-digit pace the country achieved at various times during the past three decades.

This was more bad news for western companies with significant exposure to China’s heavy industry sector, which has been particularly badly affected by the broad economic downturn. The trend has created real problems for such companies’ shareholders and employees, and this has naturally given rise to negative headlines in the western media.

In our view, however, the headlines tend to overlook or underrate the key fact that the composition of China’s GDP growth has changed. While the contribution from investment—traditionally the main growth driver—has declined as a share of GDP, consumption and services have powered ahead. They now account for more than half of GDP and considerably more than half of the growth.

This is fully consistent with China’s goal of rebalancing its economy in order to avoid the middle-income trap, and counts as a major policy achievement. It’s good news for investors, because it points to more sustainable, if lower, GDP growth over the long term.

Much of this good news isn’t getting through, however, partly because of the western media’s understandable bias towards reporting from the perspective of western companies, which have been caught on the wrong side of China’s economic policy shift.

For investors who want a more balanced and realistic picture of the risks and opportunities in China today, we think that it helps to think in terms of two Chinas—the old and the new.

New China Thrives as Old China Wilts

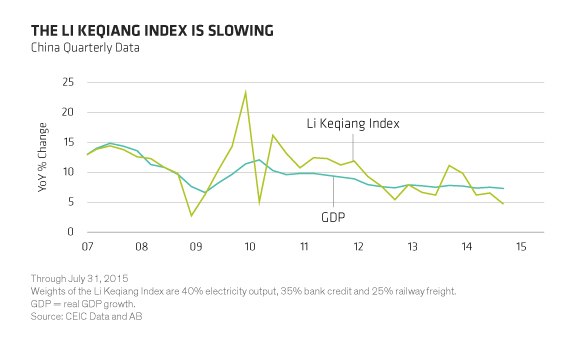

A good symbol of the “old” China is what’s widely known as the Li Keqiang Index, named after China’s premier. This was popularized by The Economist magazine in 2010 after it became known that Li, when he was the Party’s senior official in Liaoning province, had focused on three indicators which he considered to be more reliable than local GDP figures. These were railway cargo volume, electricity consumption and loans disbursed by banks.

The Economist recreated the index to apply to China nationally. The magazine’s intentions were partly tongue-in-cheek, but the index came to be used quite widely as a second reading on China’s GDP figures. This made sense up to a point, as the indicators were a fair reflection of an economy then dominated by heavy industry and state-run banks.

Today, the value of the index lies more in illustrating the difference between the old China and the new one. As the Display shows, the Li Keqiang Index—which tends to be volatile, given its narrow base— is significantly underperforming GDP. Meanwhile the “new economy” sectors favored by government policy, such as consumption and services, remain relatively resilient, as reflected in the overall GDP trend.

Not Just Doom and Gloom

For active investors, this is a good indication as to where opportunities lie. Indeed, the strength of the consumer sector can be seen in recent data showing strong quarterly year-on-year growth in segments such as 4G mobile contracts (up 115%), holiday travel (84%), movie box office receipts (55%) and gross merchandise value for online retailer Alibaba (34%).

While it would be wrong to paint China’s prospects in the rosiest colors, we think it’s just as wrong to see the country as nothing but doom and gloom. What’s necessary, in our view, is a balanced and holistic perspective: an understanding of China as a country in economic transition and which, for the foreseeable future, consists of two economies, old and new.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.

Chief Investment Officer—Asia-Pacific ex Japan Value Equities

Stuart Rae has been Chief Investment Officer of Asia-Pacific ex Japan Value Equities since 2006. He served as co-CIO of Australian Value until 2012, and was CIO of Australian Value Equities from 2003 to 2006. Rae joined the firm in 1999 as a research analyst covering European consumer-cyclicals stocks. Previously, he was a management consultant with McKinsey for six years in Australia and the UK. Rae earned a BS (with honors) from Monash University in Australia in 1987 and a PhD in physics from the University of Oxford in 1991, where he studied as a Rhodes Scholar. Location: Hong Kong

Director—Asia Pacific Fixed Income

Hayden Briscoe, Director of Asia-Pacific Fixed Income, joined AllianceBernstein in August 2009 and is responsible for the Asia-Pacific Fixed Income business and for managing global and regionally focused portfolios. He was previously a senior member of the Fixed Interest team at Schroders Australia, where he was responsible for domestic and global fixed-income funds and served on the multi-asset team. Prior to joining Schroders, Briscoe spent six years with Colonial First State Investments, where he managed local and global bond funds and had tactical asset-allocation responsibilities. He spent nine years with Bankers Trust in investment banking, starting out in the treasury, trading bonds, before becoming a proprietary trader. Briscoe moved to Macquarie for a short time after the Bankers Trust merger before he joined Colonial First State. He holds a BA in economics from the University of New South Wales. Location: Hong Kong

Related Posts

Copyright © AllianceBernstein