Investment advice is shaped by the business models of those providing it

by Tom Brakke, Research Puzzle

In seeing the title above, you might think that you will be getting advice on how an investment organization can create a better business model. Given that the conditions are ripe for industry disruption, firms certainly should be considering how they can stay ahead of the coming changes.![]()

But this posting is about something else, namely, the tendency for the investment advice that is given to a client (or, if discretion has been granted, the action that is taken on behalf of a client) to be a function of the business model of the investment provider.

At one level, that’s obvious. If a provider does not have access to a particular product, a client who relies solely on that provider for investment assistance will not invest in it.

More generally, it’s easy to lose sight of how investment advice is shaped by the business model of the person and/or organization providing it — and to misjudge the impact that it can have in practice.

Observers are quick to point to firms where commissions are paid to those who sell investment products. While many brokers and agents have been rebranded as “financial advisors” and “wealth managers,” they still must navigate significant conflicts of interest that are part and parcel of the business model. It’s not that a provider can’t navigate them, it’s just that it’s a challenge to do so.

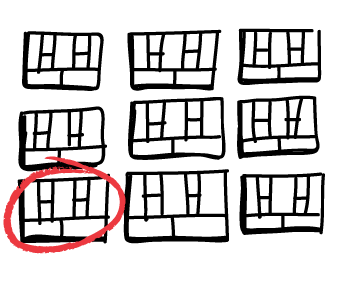

There’s no disputing the trail of violations and settlements that are evidence of the structural and cultural issues that such firms engender. Theirs is a business in which compensation is tied to action, explicitly and implicitly. When brokers move from firm to firm, they can get big bonuses; the clients that follow them get re-papered and sometimes put into new products, incurring costs they otherwise wouldn’t have.![]() A regular staple of publications aimed at brokers is a grid showing the payouts on various products at firms across the industry; the message is inescapable.

A regular staple of publications aimed at brokers is a grid showing the payouts on various products at firms across the industry; the message is inescapable.

While not as obvious, registered investment advisors (who are held to “the fiduciary standard,” requiring them to put the best interests of the client in front of their own) can face similar issues. Their firms make more money when they do certain kinds of things, which has a way of making them more money too. And it’s fairly easy to identify situations (think of cutting debt versus keeping money in a portfolio) where the interests of the advisor and the client can be at odds.

In addition, the need for operational efficiency can lead to a standardization of advice or action that is in the interest of the organization rather than the client. Size is a powerful force for profitability in an investment advisory firm. It offers some benefits for clients, but the flip side is that solutions can become less tailored to the needs of a particular client despite the availability of more resources overall.

The dangers of “business model advice” are not confined to retail investors. Institutional asset owners that don’t have an in-house investment staff rely on providers for many different services, including the education of decision makers. What is the likelihood that the education provided will include a balanced look at an important issue if an advisor or asset manager will benefit from imparting a certain point of view? If a provider’s organization is built upon active management, do you think that passive approaches will get a fair hearing (or vice versa)?

Large asset owners are not immune to the problems. For example, since asset managers are paid based upon assets under management, how likely are they to give an objective look at the opportunities and risks for the strategies that they manage? If their asset class gets overvalued or it becomes harder to outperform their benchmark, do they call their clients to tell them that is the case? Rarely. To do so is business suicide. So, asset owners don’t get the investment intelligence from their managers that is their due.

Furthermore, we have segmented the investment landscape and made it more complex and assigned roles in ways that can obscure the ultimate purpose of an investment function. In a recent essay, Ben Hunt wrote, “Builders build. Drillers drill. Stock pickers pick stocks.”![]() We shouldn’t be surprised if our interests lack alignment; when we hire specialists and incent them based upon relative performance, they are bound to grind away at those specialties in little worlds of their own. They work quite apart from and sometimes even at odds with the ultimate goals that we have.

We shouldn’t be surprised if our interests lack alignment; when we hire specialists and incent them based upon relative performance, they are bound to grind away at those specialties in little worlds of their own. They work quite apart from and sometimes even at odds with the ultimate goals that we have.

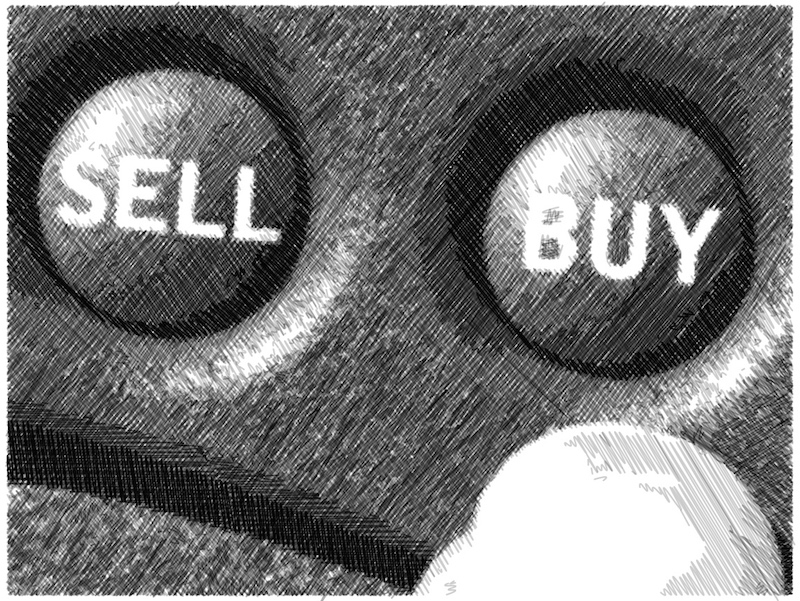

These are conflicts that investment professionals and their clients face in an industry that is out to arbitrage every edge,![]() hone every advantage, and fight for each bit of a client’s “share of wallet.” The path of least resistance will always be in the direction of the business model. To deliver (or receive) true value, you need to know when it is best to go another way.

hone every advantage, and fight for each bit of a client’s “share of wallet.” The path of least resistance will always be in the direction of the business model. To deliver (or receive) true value, you need to know when it is best to go another way.

Copyright © Tom Brakke, Research Puzzle