by Mawer Investment Management, via The Art of Boring Blog

I spent some time this weekend listening to the audiobook Eleven Rings by Phil Jackson. Jackson is among the most decorated basketball players and coaches in the history of the NBA, and was the assistant, and then head, coach of the Chicago Bulls from 1989 to 1998, during which the Bulls won six championship titles. He also coached the L.A. Lakers to five wins between 2000 and 2010. In addition to the thirteen championship rings Jackson earned as both player and coach, he earned a reputation for his unique leadership style. Eleven Rings is packed with lessons on leadership and includes one lesson that is very relevant to investors’ current relationship with central banks.

One of the core tenets of Jackson’s approach to leadership is allowing individuals to discover their own destiny by forcing them to accept individual responsibility. As Jackson describes, most basketball players are used to letting their coach think for them. When they run into a problem on the court, they look to the sidelines nervously, expecting “Coach” to come up with an answer. And while many coaches accommodate this kind of behaviour, Jackson preferred his players think for themselves in difficult situations.

As an example, there is a standard rule of thumb in the NBA that when an opposing team goes on a 6-0 run, you call a time-out immediately. But to the chagrin of many of Jackson’s coaching staff, he would often let the play continue, thereby forcing his players to find a solution on their own. This would force solidarity on the team and would foster what Michael Jordan would later call “collective think power.” It worked well.

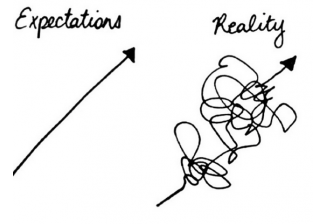

It is this kind of space, free from dependency on authority, which is often needed to foster individual responsibility. And it is precisely this kind of space that is lacking in the relationship between central banks and investors today. We have built a dependency on central banks that is unhealthy.

Fifteen years ago, fund managers could be surprised to discover that the Bank of Canada raised interest rates overnight. That type of situation is almost inconceivable today. We now operate in a world in which every bit of communication, down to the most insignificant press release, is carefully crafted and released in a tightly controlled manner. And investors cling to every little word uttered by central banks. Never in the history of stock markets have central banks held so much of centre stage.

This new relationship has been even more obvious in recent months. It seems like investors all over the world have collectively paused to watch what the Federal Reserve and other central banks will do this month. Will the Fed raise interest rates? Will the People’s Bank of China stimulate the economy? Will the ECB or the Bank of Japan engage in further quantitative easing?

To some extent, this kind of investor reaction is hardly surprising. Since the Global Financial Crisis, investors have learned to give central banks respect as they have demonstrated an unprecedented willingness and ability to influence asset prices. Every time the global economy has hiccupped over the last five years, the central banks were there on the sidelines, ready to pump markets with liquidity. There is a reason why the adage "don't fight the Fed" exists. Many traders have lost their shirts betting against the central banks.

This dependency comes at a cost. As Zero Hedge, an online news source covering financial markets, recently wrote, "investors seem to have abdicated their responsibilities for assessing growth, cash flows and value, and taken to watching the Fed and wondering what it is going to do next." As an example, we need only to consider recent reactions to China. In the last few months, investors have collectively awoken to some of the risks in the Chinese economy (As we have previously written about here, here, and here). Volatility spiked, Chinese equities dropped, and the most exposed economies and businesses were hit hard.

But as much as this market drop was painful, it was not an altogether unexpected or inappropriate reaction. When asset prices detach from their fundamentals for long enough, investment gravity (market forces) eventually bring them back in line. In this case, the risks in China’s economy were likely not well reflected in asset prices and so they corrected. Fair enough, except the fears around China have been cautiously relenting and not because China’s economy has miraculously improved; but rather because investors seem to be hoping that the Chinese will intervene. Central banks to the rescue (again)!

(As this goes to publish, we notice the fear of the data is again outweighing the hope of central bank stimulus.)

While it would be foolish to ignore the influence that central banks have today, investors need not be sucked into an unhealthy attachment to them. Although the hoopla of central bank activity may be hard to ignore this month—as the circus surrounding them can be intense—central banks are not the right “coach” for investors and we needn’t look to them so incessantly for a solution.

We suggest imagining what Phil Jackson would have us do: look inward, towards sound investment principles; the kind that have served investors well for decades.

This post was originally published at Mawer Investment Management