Great expectations

by Erik Swarts, Market Anthropology

There’s an old saying, "If you have no expectations, you'll never be disappointed.” Some might even suggest it's universal wisdom – a tenet that neither leads one astray nor fools with randomness. And while the long reflection of the more than six year bull run in equities benevolently nurtured a Zen approach towards risk (i.e. don't think, just buy), the past year has introduced a challenge to that dogma, as the Fed stepped away from quantitative easing and looked to further normalize monetary policy through posture, now perhaps practice. The end result, has lengthened the expectation phase for this policy cycle, commensurate with the extraordinary span of ZIRP. As such, the ambiguity – either intended or not, has muddled the macro waters for participants to gauge conditions of where they are actually swimming.

When it comes to the US dollar, this prolonged and fuzzy chapter in the face of easing across much of the developed and emergent world, cleared the airspace for the buck and real yields to take flight in; which has already tightened financial conditions – in our opinion, with even greater capacity than what the Fed could/will engender with marginally raising the fed funds rate off ZIRP over the next year.

Here's Morgan Stanley in August characterizing an impact of a stronger dollar:

The role of the USD in financial conditions is also significant. We find that a 1-month 1% increase in the nominal trade-weighted exchange value of the USD versus major currencies would add roughly 0.14 points to the Chicago Fed's adjusted financial conditions index, indicative of substantially tighter financial conditions. To put it in perspective, a 10bp widening of the 2-year/3-month Treasury yield spread would have an equivalent impact on financial conditions.

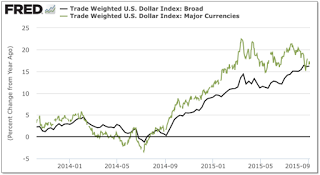

With the Fed's preferred measure of the dollar (broad index) gaining more than 15 percent over the past 12 months and the DXY trade-weighted index cresting in March over 20 percent higher, financial conditions have tightened swiftly. Considering the dollar's reserve status throughout the world and the more than 9 trillion in credit outstanding outside the US, the impact has been especially severe overseas.

With the Fed's preferred measure of the dollar (broad index) gaining more than 15 percent over the past 12 months and the DXY trade-weighted index cresting in March over 20 percent higher, financial conditions have tightened swiftly. Considering the dollar's reserve status throughout the world and the more than 9 trillion in credit outstanding outside the US, the impact has been especially severe overseas.  Moreover, taking into account the move higher in real yields from the initial suggestion of an end zone for QE by Bernanke in May 2013, through the completion of the taper last October, markets have reflected tighter financial conditions for some time.

Moreover, taking into account the move higher in real yields from the initial suggestion of an end zone for QE by Bernanke in May 2013, through the completion of the taper last October, markets have reflected tighter financial conditions for some time.

We know in past cycles – and characteristic of markets forward discounting dynamics, the dollar strengthens during the expectation phase of tightening and typically begins to weaken directly before as markets become confident that the Fed will move. Commonly understood by traders as buy the rumor – sell the news, we've playfully suggested it’s become, buy the hype – sell the bluff. The bluff of course being, the posture and expectations shaped from more conventional tightening cycles, would have stronger influence within the financial markets, than the actual structural significance of a quarter point hike – or less. Granted, this is par for course with the Fed and monetary policy over the past 6 years, where the behavioral reflex inferred was arguably as or more important than the structural transmission mechanisms themselves.

That said, having their cake and eating it too has proved difficult for the Fed. While the US equity markets had enjoyed the warm gentle breeze of disinflationary conditions over the past several years; a consequence of elongating the expectation phase of the next pivot in posture or policy, engendered a vacuum in the currency markets that supported and strengthened the dollar – and which ultimately has worked against their goal of achieving a 2 percent inflation target.

Just recently, Stanley Fischer– Vice Chairman of the Fed, remarked on the dollar's sizeable impact on inflation and the economy in his Jackson Hole speech this August.

In the first instance, as already noted, core inflation can to some extent be influenced by oil prices. However, a larger effect comes from changes in the exchange value of the dollar, and the rise in the dollar over the past year is an important reason inflation has remained low (chart 4). A higher value of the dollar passes through to lower import prices, which hold down U.S. inflation both because imports make up part of final consumption, and because lower prices for imported components hold down business costs more generally. In addition, a rise in the dollar restrains the growth of aggregate demand and overall economic activity, and so has some effect on inflation through that more indirect channel.3

To get a sense of the timing and magnitude of these exchange rate effects, chart 5 shows dynamic simulations of a 10 percent real dollar appreciation, based on one of the models we maintain at the Federal Reserve.4 The estimated pass-through from import prices to consumer price inflation occurs relatively quickly, with effects becoming evident within a quarter and the bulk of the overall effect occurring within one year. By contrast, the portion of the dollar effects on inflation that work through the channel of overall economic activity occurs with considerable lags. In the model shown here, the appreciation has its largest effect on gross domestic product (GDP) growth in the second year after the shock. Thus, it is plausible to think that the rise in the dollar over the past year would restrain growth of real GDP through 2016 and perhaps into 2017 as well. The rise in the dollar since last summer, of about 17 percent in nominal terms, with its associated declines in non-oil import prices, could plausibly be holding down core inflation quite noticeably this year. - U.S. Inflation Developments, Stanley Fischer

Weighing into the inflation/policy debate this past Friday, Kenneth Rogoff, the esteemed professor of economics and public policy at Harvard, questioned the logic surrounding the growing idea that the Fed's liftoff from ZIRP will be a one-off event. Concerned with the lack of inflation and arguing the Fed should wait to raise until they see the whites of inflation’s eyes, the idea of lifting rates just to prove they can, doesn't seem to be worth the risk for Rogoff.

"What is the logic of doing it, also?" he said in response to a question on the merits of a rate hike followed by a long pause. "It's very asymmetric. If we see inflation, they can start raising rates, and if you go in the wrong direction, it's harder to do something about it."

"The models have not been very good for a long, long time since the financial crisis, and why you would want to rely on that and not be more on seeing inflation I don't understand," said Rogoff. "After your models have been so off for so long- your ship's been thrown around in a storm and you don't know where you are when you land- you kind of want to see the inflation more than usual."

The danger in signaling a long pause, or potentially having to reserve a hike soon thereafter, is that it fosters unnecessary uncertainty, the professor asserted.

"You're trying to create some certainty about what your path is, to have a reaction function people understand," Rogoff said. – Ken Rogoff Slams One of the Most Popoular Theories for What the Fed Should Do Next, Bloomberg

What we'd argue that Rogoff is missing today (that Fischer gets, see Here) with respect to policy at the zero-bound, is the significance of the signal itself to the markets (as small as it may be), which greatly influences confidence and consequently, inflation expectations. From a behavioral point of view, QE and ZIRP have not been considered a positive station for the markets for some time; rather much the opposite – a confirmation in the belief that the economy still requires further external support. From a market perspective, maintaining current policy is in and of itself – disinflationary. Notwithstanding the tepid measure of inflation over the past year – which as we contend is more a consequence of the currency markets and the drawn out and ambiguous expectations of this policy cycle; the underlying conditions in the economy – from near full employment to robust business and construction spending – at the very least supports further normalizing policy and posture from a crisis stance.

As counterintuitive as it may sound, but in-line with the coriolis-like effect on expectations and outcomes for this cycle (i.e gold, silver and commodities round-trip across ZIRP and QE), we'd argue financial conditions will loosen (i.e. real rates decline) over time as the Fed either finally marginally moves off ZIRP next week or provides greater clarity of policy going forward. Whichever the case, we believe the magnitude of the rate hike will be exceedingly modest – and consequently, the dollar's decline from the relative performance extreme will have greater positive impact on the global economy and inflation expectations, than a governor on growth of higher nominal yields.

As counterintuitive as it may sound, but in-line with the coriolis-like effect on expectations and outcomes for this cycle (i.e gold, silver and commodities round-trip across ZIRP and QE), we'd argue financial conditions will loosen (i.e. real rates decline) over time as the Fed either finally marginally moves off ZIRP next week or provides greater clarity of policy going forward. Whichever the case, we believe the magnitude of the rate hike will be exceedingly modest – and consequently, the dollar's decline from the relative performance extreme will have greater positive impact on the global economy and inflation expectations, than a governor on growth of higher nominal yields.

For a few of our own Great Expectations, see Here.

Copyright © Market Anthropology