Something most investors simply cannot accept

by Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense

“There’s only one absolute truth about investing…it isn’t easy.” – Howard Marks

Investing is hard.

Markets are extremely challenging.

Beating the market is not easy.

Coming to these realizations is maybe the hardest part about investing because we all like to assume that we’re above average. Case in point — a few years ago MarketWatch columnist Chuck Jaffe shared some anecdotal evidence on the irrational overconfidence many investors have in their own abilities. Active investors at a Fidelity Traders Summit conference were surveyed to see how many of them expected to meet or beat the market’s return over the following 12 months. Over 90% of these investors said they would outperform.

I’ll take the under on that one every time.

Overconfidence surely affects novices, but professional investors are probably the ones who are the biggest culprits of overestimating their own investment skill. Some combination of ego, career risk and an ultra-competitive gene suggest that this trait won’t be going away any time soon. Jim O’Shaughnessy provided a perfect example of this on his blog recently in a re-print from his book, What Works on Wall Street:

Professor Nick Bostrom, the Director of the Future of Humanity Institute at Oxford University points out, in his paper Existential Risks: Analyzing Human Extinction and Related Hazards that “Bias seems to be present even among highly educated people. According to one survey, almost half of all sociologists believed that they would become one of the top ten in their field, and 94% of sociologists thought they were better at their jobs than their average colleagues.”

The great thing about the sheer amount of overconfidence in the markets is the fact that certain groups of investors will always be able to take advantage. The downside is that there will also always be investors who are being taken advantage of, whether they’re willing to accept this fact or not. Someone always has to take the other side of a winning bet.

In his latest quarterly letter, legendary investor Howard Marks does a deep dive into how difficult it is to outperform:

Why should superior profits be available to the novice, the untutored or the lazy? Why should people be able to make above average returns without hard work and above average skill, and without knowing something most others don’t know? And yet many individuals invest based on the belief that they can. (If they didn’t believe that, wouldn’t they index or, at a minimum, turn over the task to others?)

Marks go on to say that only a small percentage of investors possess enough superior skill to outperform over the long-term. Carl Richards penned the term ‘the behavior gap’ to describe the difference between the returns reported on an investment and the returns actually earned by investors. I think there’s also a ‘Lake Wobegon gap’ that can explain the underperformance in most actively managed strategies, as certain individuals or groups of investors are unwilling or unable to admit that they don’t have what it takes.

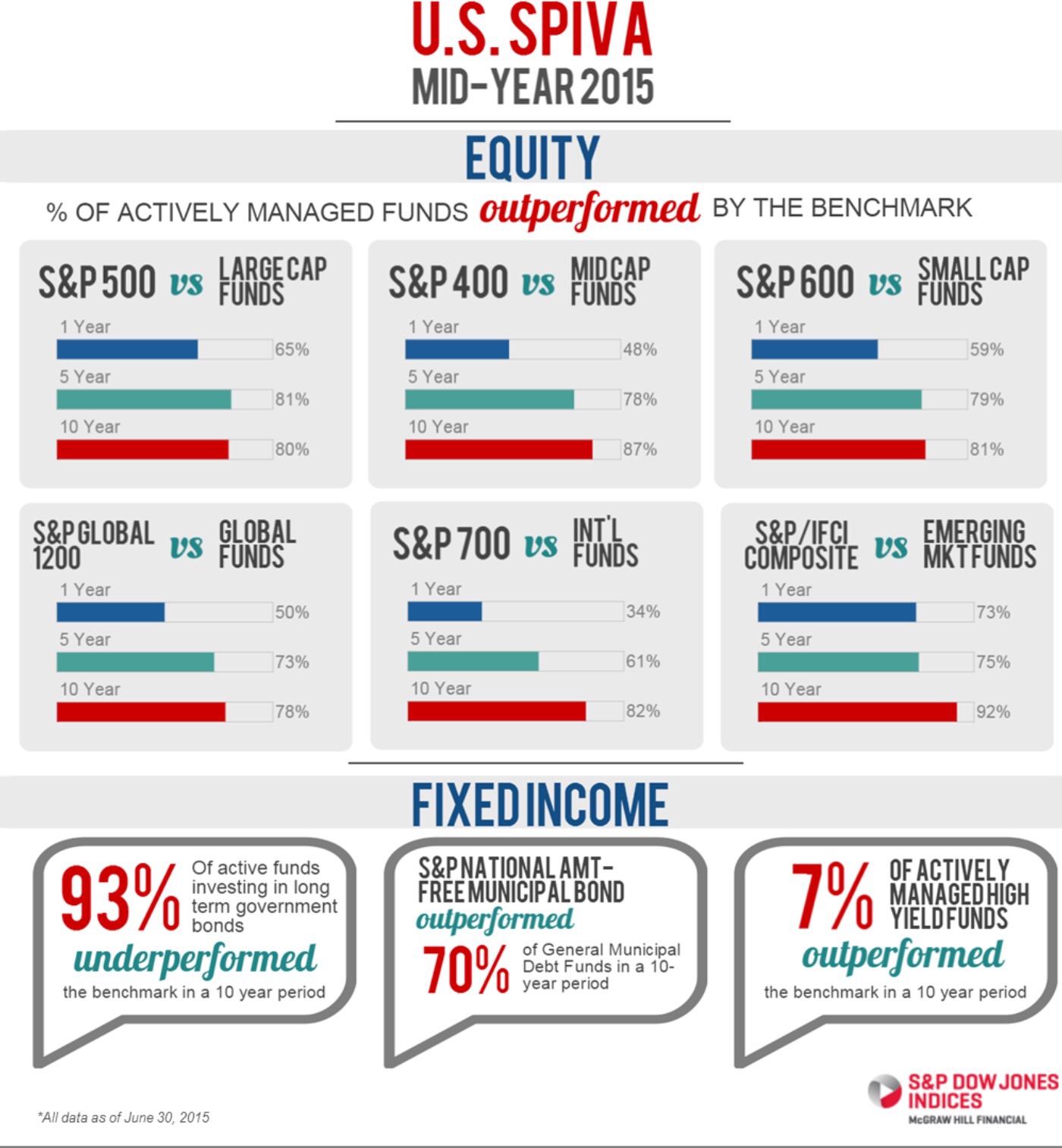

The paradox of “average” returns is that they will almost certainly always be above average in the long run because of compounding costs, poor market timing and overactivity by this group of overconfident investors. The latest SPIVA scorecard provides a good illustration of this:

These numbers shouldn’t be all that surprising to anyone when you take into account the long-term impact of costs and the zero sum nature of benchmark investing. Individuals and organizations spend so much time and effort trying to beat the market that they never stop to consider how easy it could be to outperform their peers or other professional investors by simplifying.

Most would do much better for themselves if instead of trying to beat the market, they first focused on not underperforming the funds they’re invested in, regardless of how those funds perform relative to the market. When you think about investing in terms of behavior and mistake minimization and not just outperformance, you begin to align your portfolio with your actual goals, the only thing that truly matters.

Some people seem to think index funds are going to continue to gain market share from active funds over time as more and more people do the math on passive vs. active investing. I agree, but only up to a certain point. I think human nature is such that index funds will never gain a majority share for the simple fact people are so competitive. We like to gamble and take chances. It’s in our nature to try to be the best.

We also have to remember that there’s much more that goes into the investment process than beating an arbitrary index or benchmark. The questions investors need to ask themselves are simple:

Do I really need to try to outperform the market?

Or should I be content with outperforming the majority of my investing peers and not underperforming my own investment plan?

Sources:

Poll Shows Wide Range of Investor Pyschology

It’s Not Easy (OakTree)

The Unreliable Experts: Getting in the Way of Outperformance (WWOWS)

Further Reading:

We’re All Smart