by James McCormack, Global Head of Sovereign Ratings, Fitch Ratings

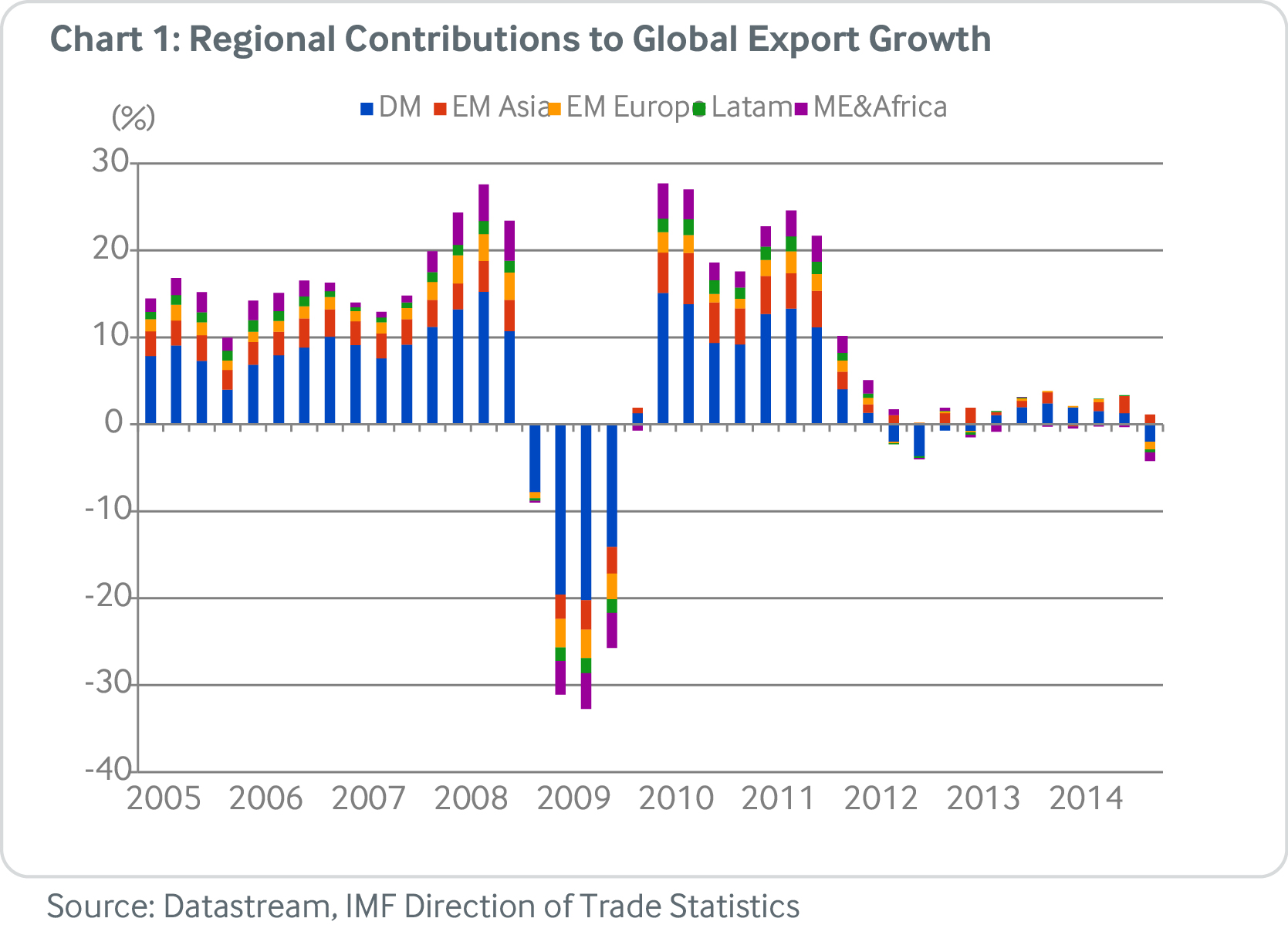

The strong post-crisis trade resurgence was short-lived. Global export volumes have consistently grown by less than 5% since 2012, and structural as well as cyclical issues limit recovery.

International trade flows have not recovered from the global financial crisis (GFC), and appear unlikely to do so soon. This is not “the end of globalisation” – as suggested by some commentators –but trade growth rates are likely to remain lower than in the mid-2000s, and more closely aligned with GDP growth. Recovery in investment spending in developed markets (DMs) – especially in the eurozone – would contribute to an increase in real trade flows, and nominal flows would be further supported by higher prices of traded goods, particularly commodities.

The Crisis: A Long Road Back

The severity of the GFC’s shock to global trade volumes meant that they had a lot of ground to regain even to reach pre-crisis levels. The 19% fall in global merchandise export volumes at the height of the GFC in late 2008 was the sharpest contraction in at least 60 years. There was also a near-synchronised 23% fall in export prices, led by steep drops in commodities. In DMs, where the crisis was centred, the year-on-year decline in volumes reached 22% in early 2009. The annual decline in emerging markets was only slightly smaller, at 17%. All regions of the world were affected by the collapse in trade, with annual declines in the US dollar value of exports in mid-2009 ranging from 18% in emerging Asia to 39% in the Middle East. Trade flows in all regions did experience very strong recoveries by 2011, with export growth rates in emerging Asia and Latin America actually accelerating to surpass those in the pre-crisis period. But the post-crisis resurgence was short-lived. Since 2012, global export volumes have consistently grown by less than 5%. Performance by value has been even worse due to the fall in global trade prices, again led lower by commodities. In April 2015, global export prices were down 16% year on year.

Longer-Term Obstacles Remain

There are several structural explanations for the continued weakness in global trade in addition to the GFC’s cyclical effects.

- Recent evidence suggests the surge in cross-border trade that began when the Chinese economy became more internationally integrated in the 1990s, enabling global value chains to develop, may have peaked. The production of goods had become more fragmented as component parts were sourced from a number of countries. But Chinese exporters are now sourcing an increasing share of component parts domestically.

- According to the World Trade Organisation, the use of trade restrictions has been rising since the crisis and trade liberalisation initiatives have slowed relative to the 1990s. Together, these developments may be contributing at the margin to the reduction in elasticity of trade with respect to GDP.

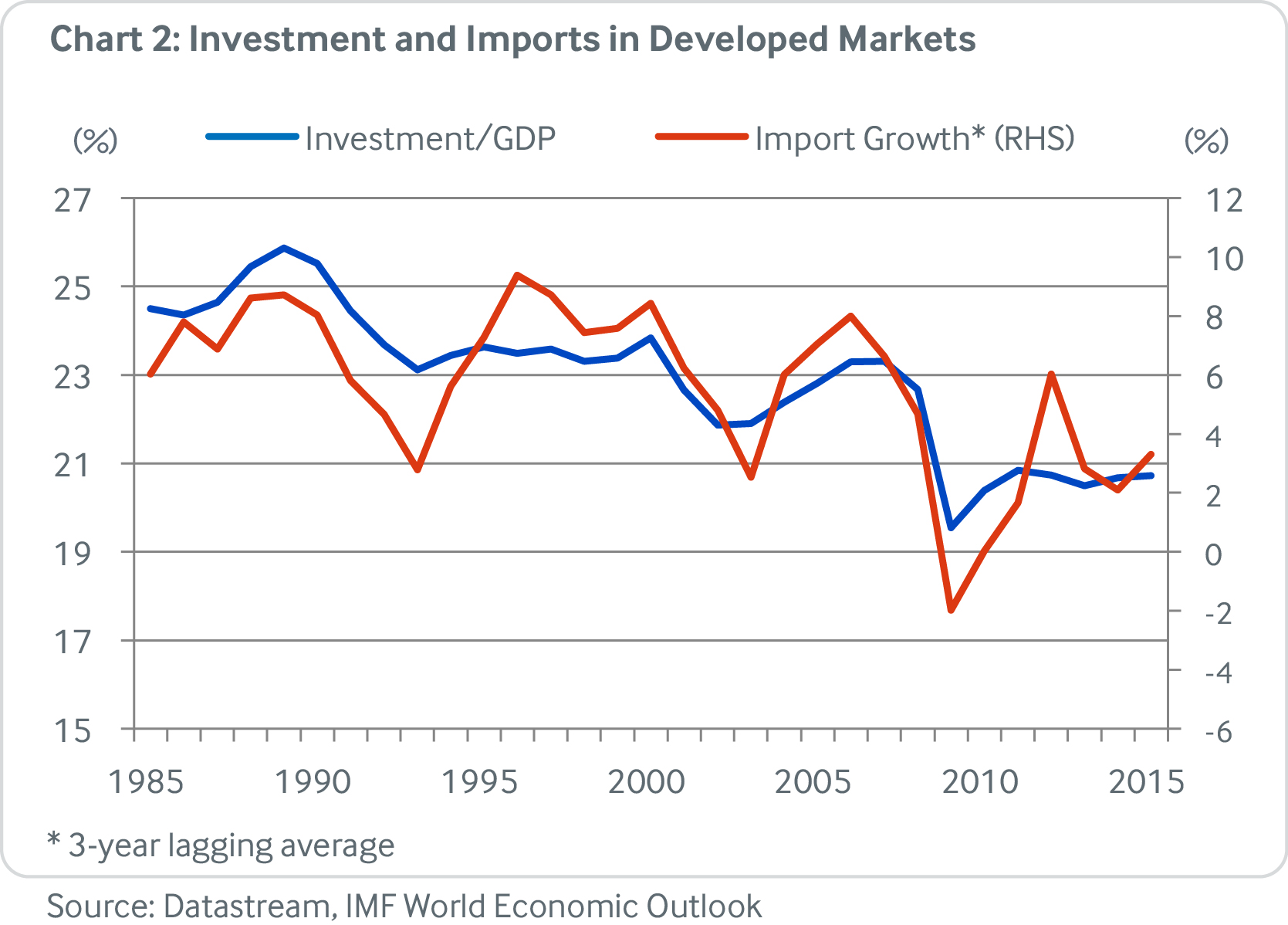

- There has been a change in the relative weights of domestic demand components, with investment falling compared with consumption and government spending. This was especially evident during the GFC, when the growth outlook was most uncertain and the availability of credit to fund investment was at its nadir. As investment spending is the most pro-cyclical and import-intensive component of domestic demand, a decline in investment tends to have a larger effect on trade.

Each of these points contributes to a fuller understanding of the recent weakness in global trade, but the effect of investment on trade’s growth rates is worth considering in more detail. The reduction in investment spending during the GFC was pronounced, but was also in line with a much longer trend (see Chart 2). This is consistent with the notion of “secular stagnation”, which postulates that investment has dipped below savings for structural reasons, and the resulting equilibrium real interest rate is very low, possibly negative. If this theory is valid, investment spending will remain weak; by extension, trade would too.

Leaving aside the current debate on secular stagnation as an explanation of persistent low GDP growth, it appears probable that there will be at least a cyclical recovery in investment and trade. Such a recovery is well under way in the US, where the investment/GDP ratio has increased steadily from its mid-2009 low. Japan has experienced an increase in investment/GDP over the same period, bringing the ratio back to pre-crisis levels.

In the eurozone, by contrast, a cyclical recovery in investment has yet to take hold, and it may be slow in coming, as post-crisis deleveraging has been more modest compared with the US and the growth outlook is less promising. When the European economic cycle does turn more fully, investment and trade will pick up. But beyond a cyclical recovery, trade growth rates in Europe – as in other DMs – could still be hindered by some of the structural issues discussed above.

Copyright © Fitch Ratings