by Chris Marx, AllianceBernstein

In a Wall Street Journal article last week, financial advisors described how exuberant investors had unrealistic expectations for stock market returns after a six-year rally. We think a more pragmatic approach should aim to beat a slower-paced market in an effort to capture compounding returns.

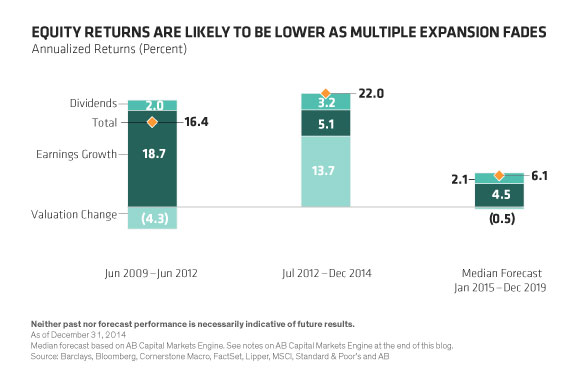

Investors and their financial planners face a conundrum. During the last six years, equities have delivered tremendous returns, with the S&P 500 up over 18.3% a year on average. The first part of the recovery was driven by a rebound in company margins on the back of aggressive restructuring (Display). In the second phase, from mid-2012, an expansion of valuation multiples kicked in as the deep anxiety following the 2008 meltdown began to fade. Over the entire period, investors were largely rewarded just for owning equities; any exposure, passive or active, growth or value, got the job done.

Market Returns Will Be Lower

This experience has created unrealistic expectations. Today, with US stock valuations at or above long-term averages, we think investors can no longer rely on multiple expansion to fuel the market and a more sober outlook for equity returns is warranted. According to our forecasts, earnings and dividends are likely to deliver about 6% annual growth over the next five years. We believe this will be the main driver of equity returns in the coming years and as a result, total returns will be much lower than in the past.

This may not seem like much compared with recent experience. But in our view, an annual return of 6% from equities still looks attractive, especially given the low yields in fixed-income markets.

More Mileage from Your Assets

With return expectations from many asset classes below long-term averages, investors will be pressed to make their allocations work harder. In this environment, relative performance—or alpha—becomes much more important to meeting long-term goals. There’s a good reason why Albert Einstein once reportedly described compound interest as “man’s greatest invention.”

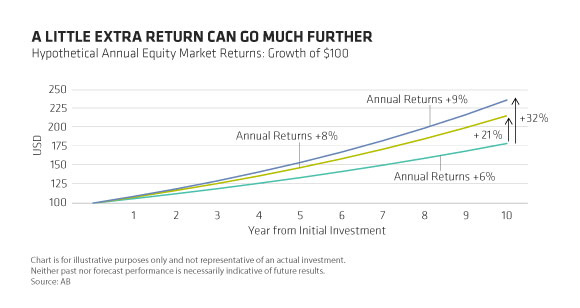

In a market with low-growth expectations, a little extra makes a big difference. As the chart below shows, an investor who put $100 in the market would receive a substantially different return by generating more than the expected equity forecast each year (Display). This is a well-known, simple investing principle that’s worth refreshing as investors adjust their expectations.

With a 6% annual return, the investor would have $179 at the end of a 10-year period. But a portfolio that beats the market by 2% would turn the initial investment into $216. In other words, the difference in annual returns is 33% more per year—and a balance of 21% more dollars at the end of the period. If the portfolio manager can outperform by 3%, those numbers increase to 50% more each year and 32% more money at the end of the period. And time is on your side because the effect is amplified year after year, as indicated by the widening gap between the lines in the chart.

Of course, in the real world, it’s not so easy to find a portfolio manager who can beat the market consistently. And market returns are never quite so smooth. Some years will be better, and some will be worse.

But relying on unrealistic expectations from the market isn’t the answer. Today, there are many active investing strategies that have shown the ability to deliver results in changing markets. By choosing a portfolio manager with high conviction and a disciplined investing process, we believe investors can significantly increase the odds of meeting their financial goals—even in a market with muted return expectations.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams.

The Bernstein Wealth Forecasting System, based on the Capital Markets Engine, uses a Monte Carlo model that simulates 10,000 plausible paths of return for each asset class and inflation rate and produces a probability distribution of outcomes. The model does not draw randomly from a set of historical returns to produce estimates for the future. Instead, the forecasts (1) are based on the building blocks of asset returns, such as inflation, yields, yield spreads, stock earnings and price multiples; (2) incorporate the linkages that exist between the returns of various asset classes; (3) take into account current market conditions at the beginning of the analysis; and (4) factor in a reasonable degree of randomness and unpredictability.

Chris Marx is Senior Portfolio Manager—Equities at AB (NYSE:AB).

Copyright © AllianceBernstein