by Urban Carmel, The Fat Pitch

Attention is gravitating to the Dollar, and for good reason.

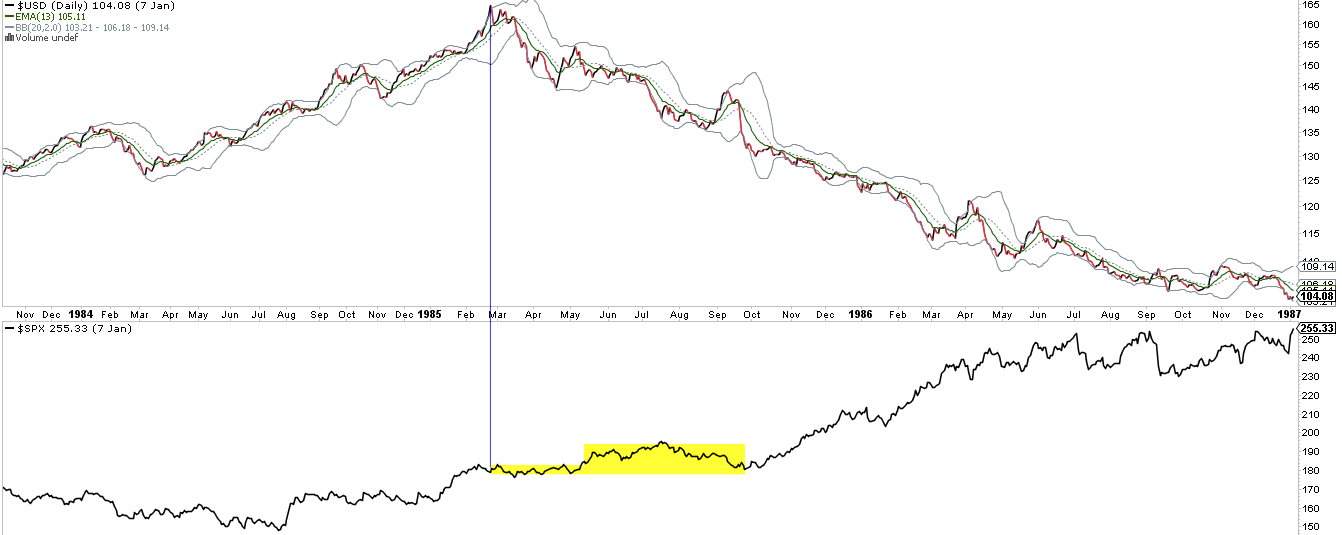

In the past year, the Dollar index is up 25%. Since 1980, the Dollar has only risen that quickly in one year once before: the period leading to February 1985. That turned out to be the Dollar’s high, unsurpassed since.

To be fair, the Dollar rose nearly 60% in the four years before its peak in 1985 versus just 31% in the most recent four years. Still, the current four year pace of appreciation has only been equalled once since: in October 2000, just after the tech bubble peak in the S&P (lower panel) in August 2000.

It’s certainly possible that the Dollar keeps rising unabated. However, if past is prologue, when the rate of appreciation becomes this extreme, the Dollar has previously taken a break, even if the trend subsequently continued higher. The rising 13 month moving average (green line) has been approximate support in the past.

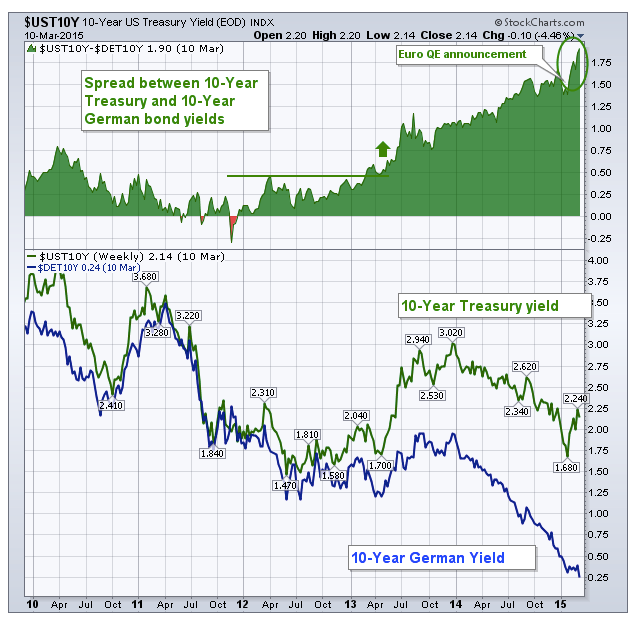

To simplify, two factors are causing a rush into the Dollar relative to the Euro (and other currencies). The first is the relative change in yields, specifically, the fall in German Bund yields together with the recent rise in US treasury yields (chart from John Murphy).

German yields have fallen with the recent advent of QE in Europe and US yields have risen with talk of the Fed beginning to raise its federal funds rate later this year.

The second factor pushing the Dollar higher is perceived longer term weakness in the European economy.

The question for us is: what are the implications for US equities? The answer is not very simple.

Over the past 30 years, there has been no consistent relationship between the Dollar (black line) and the S&P (red and black candles).

After the Dollar’s peak in early 1985, the S&P went sideways for 7 months (gaining more than 5% and then giving it all back) before resuming its uptrend. Over the next 30 years, there have been long periods when the Dollar and the S&P moved up together (green arrows) and also when they moved inversely (red arrows). The period in 1985 is highlighted below.

It would be impossible to say, therefore, that a continued rise in the Dollar poses a risk or that it is needed to support higher equity prices. Likewise, it can’t be said that a fall now would endanger, or help, equities.

The chart below looks at periods where the Dollar has risen (highlighted in yellow). What happens next? Green arrows show a rising S&P, red arrows a falling S&P and yellow arrows a sideways S&P. Conclusion: all three have taken place after the rise in the Dollar has ended. There is no consistent pattern.

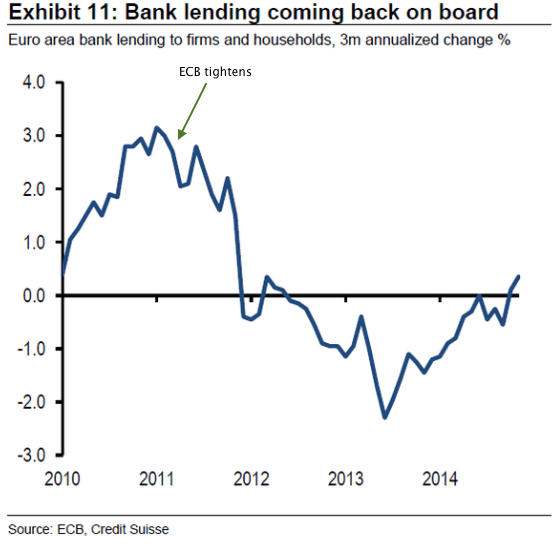

A falling Euro makes European exports more competitive. This is beneficial to their economy. If you believe that weakness in European growth is a risk to global equities, then you should welcome recent currency moves. In fact, the recent data suggests an improving European economy.

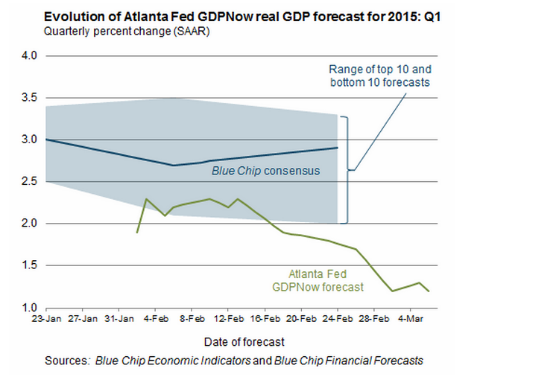

Conversely, if the Fed does, in fact, raise US rates and precipitates a further rise in the Dollar, it may well negatively impact US demand and inflation. A rising Dollar limits the competitiveness of US goods and reduces the value of foreign profits repatriated to the US. Importing lower priced foreign goods reduces inflation. If already low price inflation, part of the Fed’s dual mandate, is of concern, raising rates will be counterproductive. To note, GDP forecasts have been weakening as the Dollar has risen.

Of course, the system is dynamic. Sustained softness in the US and strengthening in Europe should stem, or reverse, the rise in the Dollar and fall in the Euro.

In summary, whether the trend in the Dollar is positive or negative for US equities depends, at least in part, on how improvements in Europe are weighed against some softening in the US. Again, the historical picture is mixed and offers no consistent evidence one way or the other.

More importantly, the S&P is driven by more that just changes in the currency. Sentiment and valuations are probably of greater importance.

Copyright © The Fat Pitch