by Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense

Bond investors are in constant fear of a replay of the 1970s when interest rates exploded higher in concert with sky high inflation, a double whammy of bad news for fixed income securities. But it doesn’t make much sense to compare the current set-up with that scenario. By 1970 the 10 year treasury yield was all the way up to 7.8%, eventually reaching over 15% in the early 1980s. That’s not even close to today’s rate levels.

A much better comparison, if you want to make one, would be the 1950s. At the start of 1950 the 10 year yielded 2.3%. It rose throughout the decade and finished at 4.7%. Inflation was relatively mild in throughout the 1950s — close to 2% annually. The 10 year currently yields just shy of 2.1%. Inflation also remains subdued for the time being.

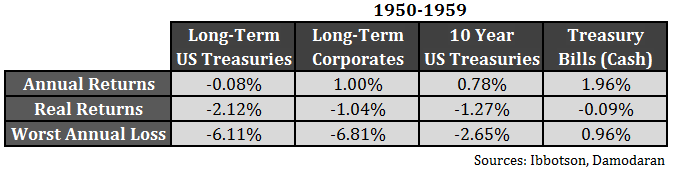

The question for investors is how did various fixed income sectors perform in that type of rising rate environment? Here are the stats for long-term treasuries, long-term corporate bonds, 10 year treasuries and cash:

Nominal returns were muted while real returns were negative across the board. The total real returns over this entire period were losses of 19.97%, 10.60%, 12.38% and 1.33%, respectively. It’s interesting that holding cash in short-term t-bills turned out to be the best performing fixed income holding. The fed funds rate was under 1% a couple of times in the 1950s but it was never zero as it is now so I wouldn’t expect the cash returns to outperform like they did back then if rates do rise from here.

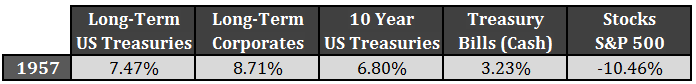

So why would an investor choose to hold bonds if this type of market is a possibility from current yields? Although those after-inflation losses sound painful, bonds still served a purpose. The 1950s witnessed a strong bull market in stocks, but when the S&P 500 fell double digits in 1957 bonds held up really well. Here are the returns from that year:

When risk strikes and stocks get hit, investors will almost certainly switch to the perceived safety of high quality bonds. In a risk-off scenario that’s generally how markets work. The worst annual returns for 10 years treasuries was minor compared to the losses in the stock market.

Although bonds could potentially lose purchasing power over the long run from current yields they can still serve a purpose in a well-diversified portfolio. Bond act as both a volatility-minimizer for those investors that can’t stomach a large stock allocation and a source of stability during stock market sell-offs for either spending purposes or liquidity for those that need to rebalance into lower stock prices.

No two markets are ever the same, so these numbers are for risk planning, not return forecasting. Rates don’t have to rise in such an orderly fashion. They could scream higher in a short period of time or just go sideways for a while. Or we could be the next Japan and see low rates for much, much longer (unlikely, but if that’s the case it’s not going to be a very fun market for U.S. stocks either).

Whatever happens to rates from here it makes sense to reign in your expectations as a bond investor based on today’s low starting yields. Bonds can still serve a purpose in a diversified portfolio, but it’s unlikely they will enhance your returns until we see much higher yields. You just have to pay attention to the duration and make sure you understand what purpose they serve.

Further Reading:

What About the 1970s?

Why Own Bonds in a Portfolio?

Sign up for email updates and my monthly newsletter by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter: @awealthofcs

Copyright © Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense