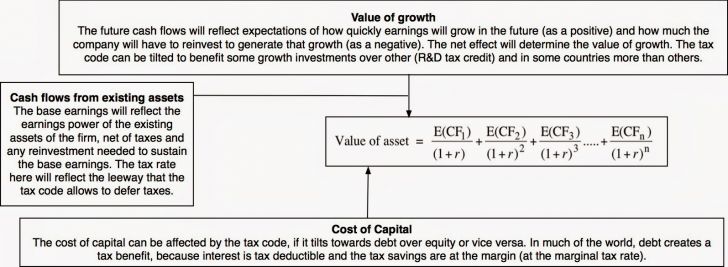

In my last post, I noted that I will be teaching my valuation class, starting tomorrow (February 2, 2015). While the class looks at the whole range of valuation approaches, it is built around intrinsic valuation, reflecting my biases and investment philosophy. I have already received a few emails, asking me whether this is an academic or a practical valuation class, a question that leaves me befuddled, since I am not sure what an academic value is. As some of you who have read this blog for awhile know, I do try to value companies, but I do so not because I am intellectually curious (I don't lie awake at night wondering what Twitter is worth!) but because I need investments for my portfolio. In the context of these valuations, I have been accused of being a valuation theorist, and I cringe because I know how little theory there is in valuation or at least my version of it. In fact, my entire class is built around one simple equation:

Put in non-mathematical terms, the equation posits that the value of an asset is the value of the expected cash flows over its lifetime, adjusted for risk and the time value of money. If that sounds familiar, it should, because it is the starting point for every Finance 101 class, a rite of passage that in conjunction with buying a financial calculator sets you on the pathway to being a Financial Yoda!

That is the only theory that you need for valuation! The rest of the class is about the practice of valuation: defining and estimating expected cash flows for different types of assets and businesses at different stages in the life cycle and estimating and adjusting the discount rate for risk and time value. Note that there is nothing in this fundamental equation that has not been known to investors and business people through the ages, i.e., the value of a business has always been a function of its cash flows, growth potential and risk and that you certainly don’t need to be mathematically inclined to be able to do valuation. So, if you don’t remember how to take first differentials or solve algebraic equations, never fear. You can still value companies.

DCF : Neither Magic Bullet nor Bogeyman

If DCF valuation is simple as its core, why does it intimidate so many? The fault lies both with its proponents and its critics. The proponents, and I would include myself on the list, have undercut the approach's usage and acceptance by:

- Over complicating DCF: It is undeniable that most discounted cash flow models suffer from bloat, with layers of detail that we not only don't need, but also make no difference to the ultimate value. These details and complexities are sometimes added with the best of intentions (to get better estimates of cash flows and risk) and sometimes with the worst (to intimidate and to hide the big assumptions). No matter what the intentions are, they make people on the receiving end suspicious.

- Over selling DCF: In the hands of bankers, analysts, consultants and managers, DCF models are less analytical devices and more sales tools, backing up a recommendation to buy, sell or change the way we do things. While that is neither surprising nor newsworthy, it does make those who are the targets of these sales pitches cynical about the process, and who can blame them?

- Over sanitizing DCF: I don't know whether DCF's proponents feel that it cannot be defended on its merits or that it is too weak to stand up to scrutiny, but they seem to want to cover up the uncertainties that are embedded into every valuation and play down any hint of story telling that may underlie the numbers or uncertainty in their estimates.

Like anyone who has ever used a DCF, I have been guilty of these practices and therefore understand the motivation. At the core, it is because we are insecure both about our understanding of DCF and our capacity to explain in intuitive terms why we do what we do. If paid to do valuation, we over compensate and believe that we will be more credible if we churn out overcomplicated, number-driven models and that our clients would not pay us, if they realized how simple the process actually was.

Those who critique discounted cash flow models (and I certainly agree that there is often to disagree with), are driven by their own share of sins, where they conflate disagreements that they have with input estimation techniques, the model-builder and model output with disagreements with the DCF process itself.

- The Baby/Bathwater syndrome: While it is an analogy that makes me cringe each time I use it, with visions of babies flying out of bathroom windows, it is apt in its description of those who take issue with how an input is estimated in a DCF and then extrapolate to conclude that the entire process is flawed. The input that creates the most angst, of course, is the risk measure used in the valuation, with even a mention of beta generating the gag reflex among old-time value investors.

- Dislike you, dislike your model: The line between a DCF model and its builder must be a gray one, since many critics seem to have trouble finding it. Not surprisingly, dislike of a user because of his or her investment philosophy, personality or style of presentation can very quickly translate into disdain about the process by which he or she values companies.

- Don’t like your answer: It is human nature but investors tend to like DCF models that deliver answers that they like and dislike models that do not. Even in my limited blog posting experiences, I have been lauded for using sound intrinsic value models, by Apple Bulls, when my valuations have suggested that Apple is cheap. I have also been blasted by often the same investors for using a flawed DCF model, when my valuations suggest otherwise.

As with the proponents, I think I understand where critics are coming from. After all, if you were constantly the target for sales pitches by analysts who use complicated DCF models to sell snake oil, you would be suspicious too.

A Return to Basics

The first step in spanning the divide is to strip away the layers of complexity that we have built into valuation over the decades and return to the equation that I started this post. At the risk of stating the obvious, I would like to draw on four simple and self-evident propositions that get overlooked or ignored frequently in the discussion of discounted cashflow valuation (DCF).

- The Duh Proposition: For an asset to have value, its expected cash flows have to be positive at some point in time, but that does not imply that the cash flow has to be positive every single year and it is quite clear that you can have a valuable business (asset) with negative cash flows in the first year, the first three years or even the first seven or eight, if it can deliver disproportionately large positive cash flows later in their lives. It is true that those whose DCF toolbox has only one model in it, usually the Gordon Growth Model (a stable growth dividend discount model), have trouble with such companies, but using the Gordon Growth Model to value most equities is the equivalent of doing surgery with a hammer: painful, ineffective and designed to come to a bloody end.

- You can hate beta (or modern portfolio theory or all of academic finance), but still love DCF: This may come as news to its worst critics but the DCF model does not come prepackaged with modern portfolio theory and its most famous handmaiden, the beta. In fact, while the discount rate in the discounted cash flow model is usually risk-adjusted and reflects the time value of money, the model itself is completely agnostic about how you adjust for risk (you can come up with your own creative ways of making the adjustment) or even whether you adjust for risk. The DCF model is a descriptive equation of a cash-flow generating asset or business, not a theory or a hypothesis.

- It is the asset's life, not your time horizon: A DCF model is designed to value an asset over it's life, and is really not malleable to what you (as the investor looking at the asset) believe your time horizon to be. If the value of an asset is the present value of cash flows over its life, what is that life? It clearly depends on the asset. If you are valuing a machine whose functioning life is only one year, all you need is one year's cash flows, but if estimating a value for a rental building with a 20-year life, it would be twenty years. With public companies that at least in theory can last forever, we do stop estimating cash flows at a point in time and assume that cash flows beyond that point continue in perpetuity, but this is an assumption of convenience, not necessity. In fact, there is nothing that stops you from replacing that perpetuity assumption with one that assumes that cash flows will continue for only 20 or 30 years after your closure year.

- You will be wrong, and it is not your fault: If you take expected cash flows (where the expectations are across a wide spectrum of outcomes) and discount those expected cash flows at a risk-adjusted discount rate, it should go without saying (but I am going to say it anyway) that the present value that you get is an estimate of value. Thus, you are almost guaranteed to be wrong when valuing assets with any uncertainty about the future, and more wrong when there is more uncertainty. So what? The market price is just as affected by uncertainty, and you are judged not by how wrong you are in absolute terms but how wrong you are, relative to other people valuing the stock.

Ten Myths about the DCF Model

While the architecture of the DCF model is simple and the truths that emerge from it are universal, there is a great deal of mythology around DCF valuation, some of it promoted by model-users and some by model-haters.

- Myth 1: If you have a D(discount rate) and a CF (cash flow), you have a DCF. As a DCF-observer, I see a lot of pseudo DCF, DCFs in drag and other fake DCFs being pushed as discounted cash flow valuations.

- Myth 2: A DCF is an exercise in modeling & number crunching. There is no room for creativity or qualitative factors.

- Myth 3: You cannot do a DCF when there is too much uncertainty, thus making it useless as a tool in valuing start-ups, companies in emerging markets or during macroeconomic crises.

- Myth 4: The most critical input in a DCF is the discount rate and if you don’t believe in modern portfolio theory (or beta), you cannot use a DCF.

- Myth 5: If most of your value in a DCF comes from the terminal value, there is something wrong with your DCF, since the value rests almost entirely on what you assume in that terminal value.

- Myth 6: A DCF requires too many assumptions and can be manipulated to yield any value you want.

- Myth 7: A DCF cannot value brand name or other intangibles.

- Myth 8: A DCF yields a conservative estimate of value. It is better to under estimate value than over estimate it.

- Myth 9: If your DCF value changes significantly over time, there is either something wrong with your valuation (since intrinsic value should not change over time) or it is pointless (since you cannot make money on a shifting value)

- Myth 10: A DCF is an academic exercise, making it useless for investors, managers or others who inhabit the real world.

Each of these myths deserves its own post and I plan to cover all of them in the next year (one myth a month). Stay tuned!

A Trial Run

I know that some of you are skeptical about my pitch but if you are, at least give the process a try. If you feel a little rusty on the basics or have questions about details, you are welcome to take my class in real time or the online version of it (which is less trying and has shorter webcasts).