by Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense

Now that the economic data is picking up, investors will turn their attention to the what the Fed will do with short-term interest rates. People have been contemplating when the Fed will raise rates for some time, but improving employment numbers and GDP growth have really ramped up the speculation on that first rate hike.

Because interest rates play such an important role in the economy and the markets, investors are concerned with what will happen to stocks and bonds once the Fed finally makes its move to tighten monetary policy. This concern makes sense from a textbook standpoint — rising rates hurt bond performance and increase the cost of borrowing for corporations, among other things.

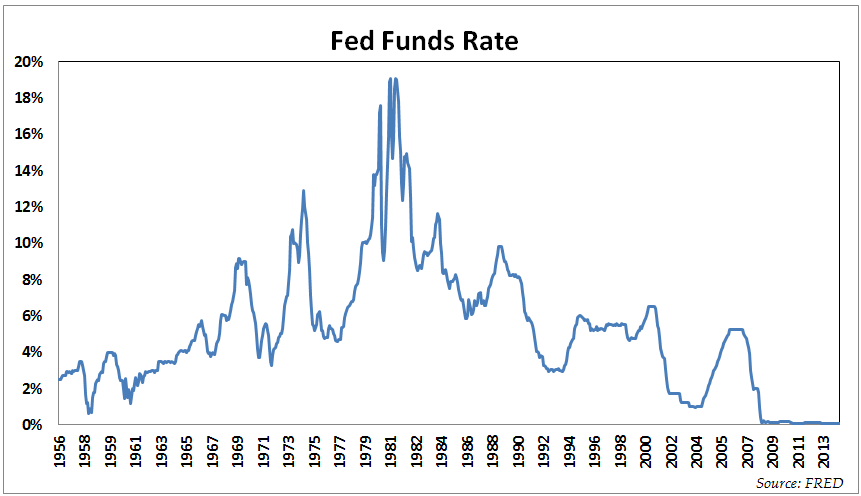

For context, here’s the Fed Funds Rate, the short-term interest rate set by the Federal Reserve, going back to the mid-1950s:

You can see the Fed has raised rates on many occasions in the past, which gives us plenty of opportunities to see the historical impact on the markets. I looked back at all of the biggest rate hikes included in this time frame to see what happened to both stocks and corprate bonds from the time the Fed started raising rates until rates peaked.

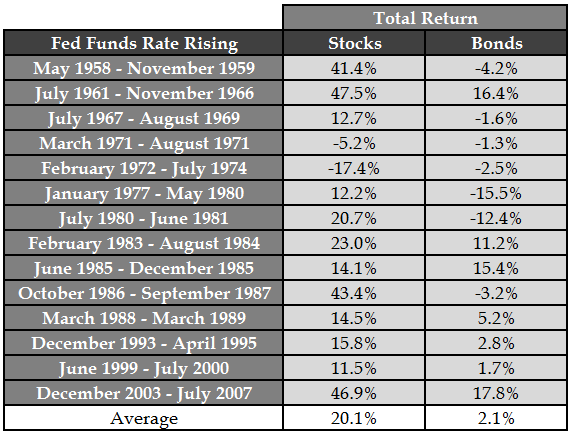

Here are each of those Fed rate hikes along with the total returns for stocks and bonds throughout the entire period of rising rates (S&P 500 and long corporate bonds from Ibbotson data):

The track record for stocks doesn’t look too bad. Only two down periods out of fourteen of the biggest rate increases and the worst one included one of the worst bear markets of all-time (1973-74). These are total returns, but the average annualized return for the S&P 500 was actually right at the long-term average of around 10% per year.

Bonds lost money half the time, which makes sense as bond prices and interest rates are inversely related. This is why bond investors have been preparing for a rise in rates for some time now, even though it just hasn’t happened yet.

There were also some interesting historical market events that occured just after these Fed rate increases ended. Rates peaked just before the 1987 Black Monday crash as well as at the beginning of the 2000-2002 bear market. And the 2007 rate hike ended just before things started to get interesting in the most recent crisis.

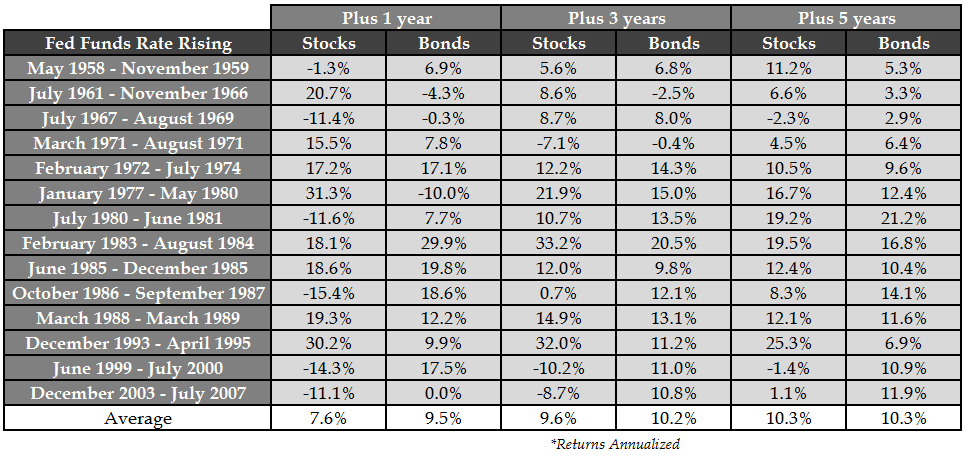

So it also makes sense to see how stocks and bonds performed after the Fed stopped raising rates. I looked out one, three and five years from the time the Fed finally stopped raising rates in each of the instances listed above. Here are the annualized returns for each using the end date as the starting point for performance purposes (click to enlarge):

On average, things look pretty good. But there’s a wide range in the performance numbers, even going out to the five year mark. Bond returns post-rate hike were juiced from higher yields and the fact that the Fed then reduced rates yet again. You can see from the graph of historical rates from above that there are plenty of peaks and then rates are quickly lowered again.

The usual caveats apply here — starting valuations, interest rates, trends, sentiment and a whole host of other factors have to be taken into account for today’s markets along with any of the historical data. Also, the total returns for bonds following most of these rate increases were so huge because the bond yields were so high before they started raising rates. That’s not the case today. The experience in 1950s and 1960s makes much more sense as a historical precedent for today’s bond environment than the 1970s, 80s, 90s or 00s.

And as usual, the markets don’t have to react a certain way just because they did so in the past. But so many investors are absolutely certain stocks and bonds are both going to get killed once the Fed finally does decide to raise rates. The historical record doesn’t clearly back up that argument.

It’s never going to be that easy.

Subscribe to receive email updates and my monthly newsletter by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter: @awealthofcs

Copyright © Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense