by Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense

The price of oil is down nearly 40% in five months, a swift fall in one of the most important and visible commodities in the world. After seeing such a crash in price, investors and pundits are quick to trot out the specific reasons for the decline.

I’ve heard many people this week give the singular reason that oil has fallen so hard so fast. While it makes for a better narrative after the fact, markets rarely move because of a single variable or data point. That would be far too easy. Usually it’s a confluence of events that gets magnified by leveraged investors and a herd mentality as everyone heads for the exits at once.

Even after the fact it’s difficult to know exactly why the markets behave the way they do. Complex adaptive systems don’t follow a set script.

The biggest case in point of all-time is the Great Depression and the stock market crash of 1929-1932. Consider the stat sheet from this colossal downturn:

- The unemplyment rate hit nearly 25%

- GDP contracted almost 27% (for comparison purposes, it was down only 4.3% in the most recent crisis)

- The stock market fell in excess of 85%

This period has been studied by scholars, economists and historians for decades, yet we still can’t find a good answer to the question: Did the stock market crash cause the Great Depression or did the Great Depression cause the stock market crash?

Here’s a list of the most heavily cited reasons:

- There was a huge increase in consumer debt in the 1920s as technological innovation advanced at a rapid pace. For the first time ever, people could buy radios, fridges, cars or clothes on credit. It’s estimated that by the end of the 1920s over one-eighth of all retail sales were made on credit.

- Margin debt in the stock market was out of control. Speculators had basically taken over the market with an excessive use of leverage. Almost 20% of the total market of listed stocks was purchased on margin loans by 1929.

- The Federal Reserve’s overly restrictive monetary policies (Ben Bernanke studied these policies and wasn’t going to repeat their mistakes during the Great Recession).

- Declining commodity prices from overproduction due to World War I, which led to tariffs and currency devaluations across the globe.

- The rigidities of the gold standard.

- President Hoover’s policy mistakes.

You could make a legitimate case for each of these reasons and many more that I’m sure I missed. But the reason every boom and bust cycle gets so out of control comes down to an abdundance or lack of confidence. Legendary author F. Scott Fitzgerald had this to say about the crash in 1931:

The most expensive orgy in history is over because the utter confidence which was its essential prop received an enormous jolt, and it didn’t take long for the flimsy structure to settle earthward. It was borrowed time anyhow – the whole upper tenth of the nation living with the insouciance of grand ducs and the casualness of call girls.

Edward Chancellor wrote one of the definitive accounts of history’s biggest manias and panics called Devil Take the Hindmost. These are his concluding thoughts on the Roaring 20s and the comeuppance that followed:

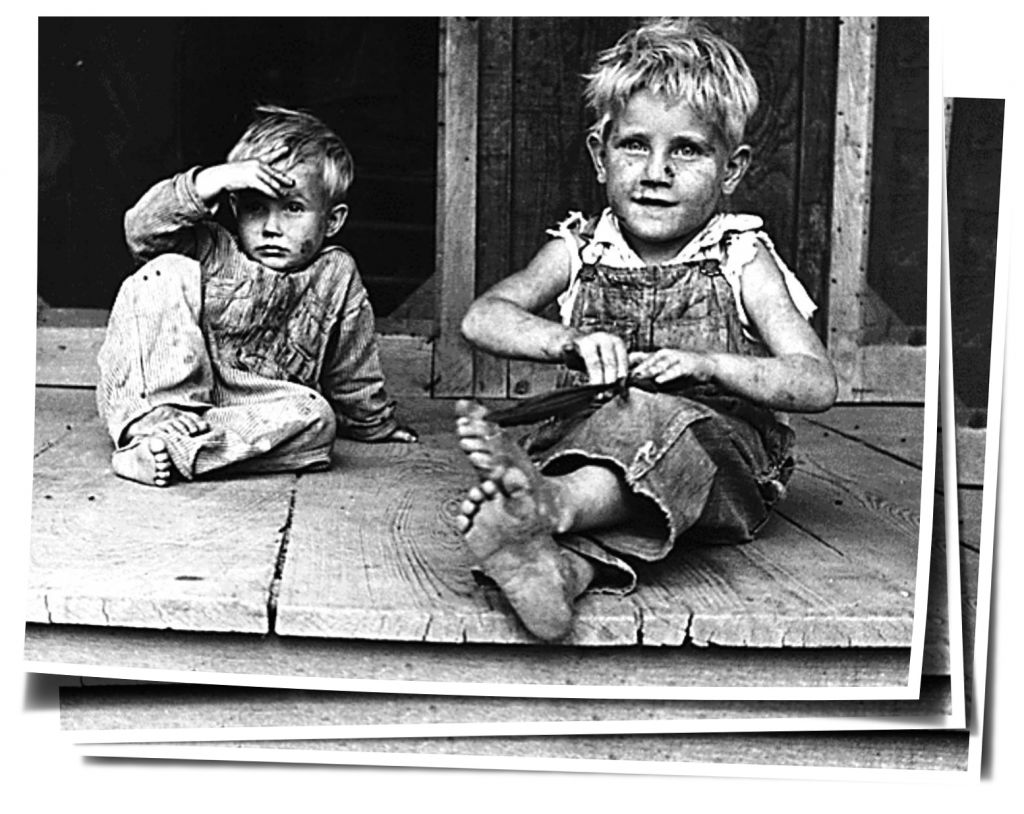

During the late 1920s, American economic reality had become dependent on a precarious vision of the future. After the Crash, when every tenet of the new era philosophy was shown to be false, Americans lost that confidence in the future which is necessary for the successful operation of the economic system. As George Orwell observed, “poverty annihilates the future.” When asset values declined, causing havoc in the banking system, a psychology of fear replaced the optimism of the previous decade. Perhaps, as some claimed, the Roaring Twenties were morally degenerate years deserving of a biblical visitation: but they were also a period when people exhibited a capacity for dreaming, a faith in the future, an entrepreneurial appetite for risk, and a belief in individual freedom. These profoundly American traits took a severe knocking in October 1929 and appeared to be extinguished during the Great Depression. They would return.

The huge gains and losses that can occur in the markets are rarely as severe as they were in the 1920s and its aftermath in the Great Depression. Whatever reasons people try to assign to a big move in either direction for the economy or the markets, the collective confidence of the participants is always involved.

Source:

Devil Take the Hindmost

Subscribe to receive email updates and my monthly newsletter by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter: @awealthofcs

Copyright © Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense