|

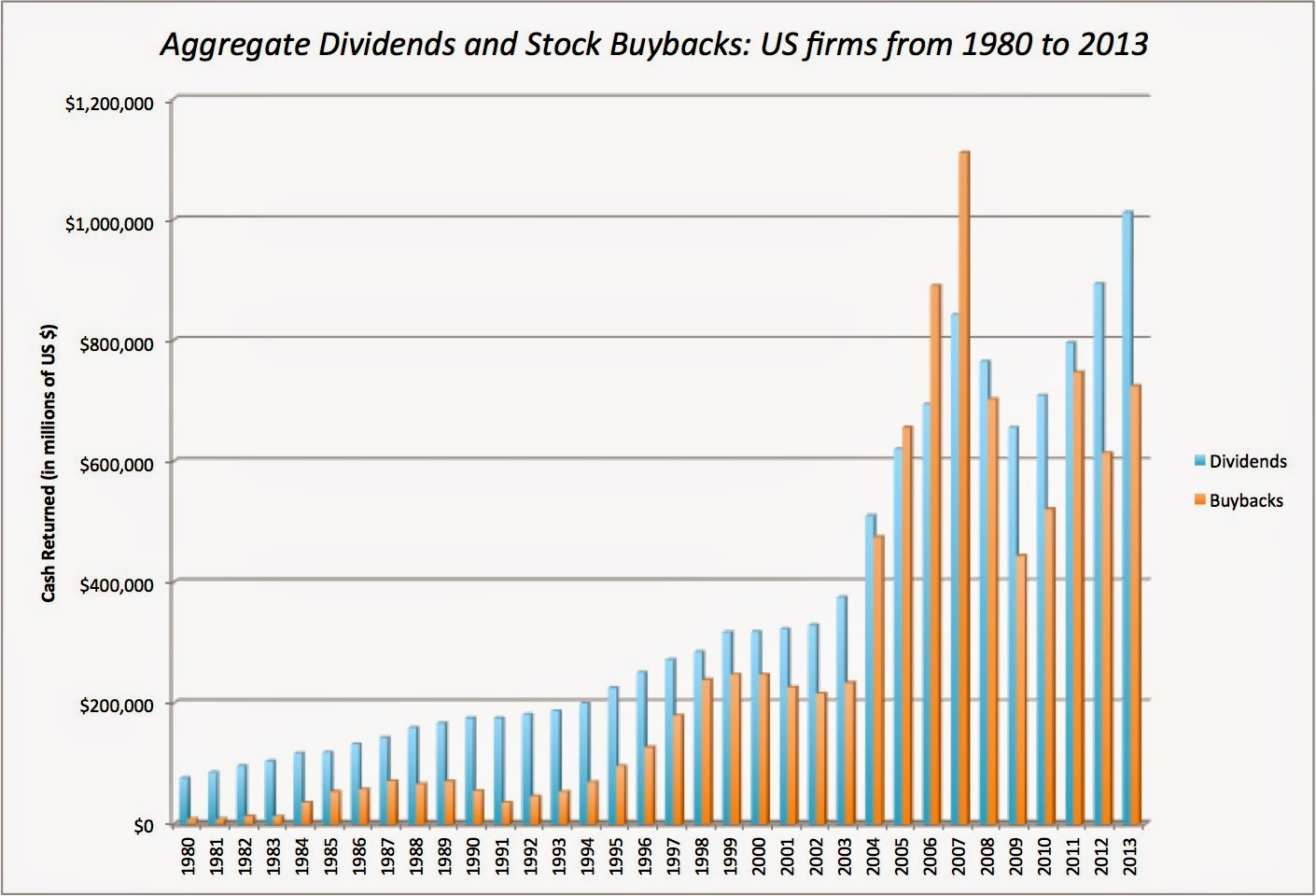

| Dividends & Buybacks at all US firms (Source: Compustat) |

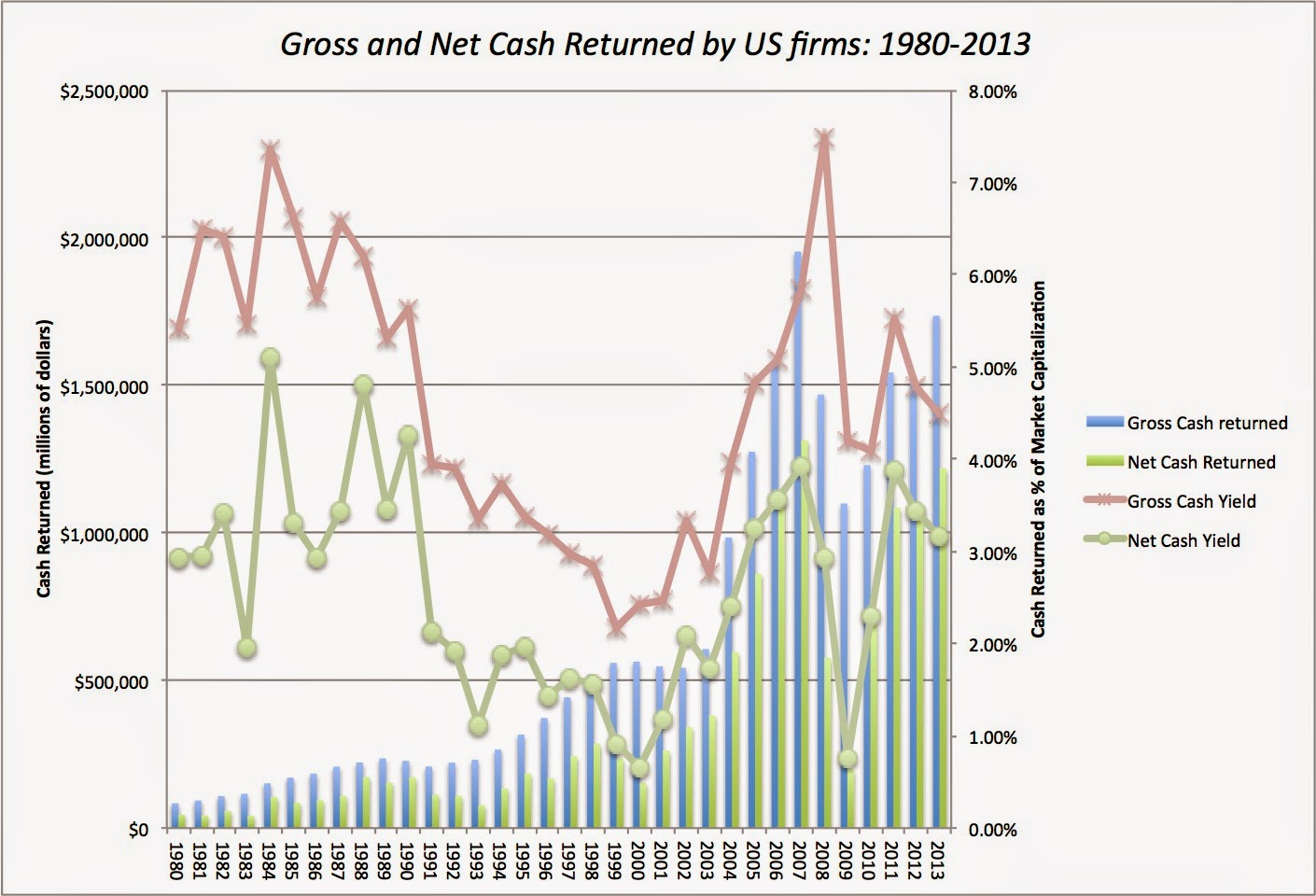

This graph backs up the oft-told story of the shift to buybacks occurring at US companies. While dividends represented the preponderance of cash returned to investors in the early 1980s, the move towards buybacks is clear in the 1990s, and the aggregate amount in buybacks has exceeded the aggregate dividends paid over the last ten years. In 2007, the aggregate amount in buybacks was 32% higher than the dividends paid in that year. The market crisis of 2008 did result in a sharp pullback in buybacks in 2009, and while dividends also fell, they did not fall by as much. While some analysts considered this the end of the buyback era, companies clearly are showing them otherwise, as they return with a vengeance to buy backs.

As some of those who have commented on my use of the total cash yield (where I add buybacks to dividends) in my equity risk premium posts have noted (with a special thank you to Michael Green of Ice Farm Capital, who has been gently persistent on this issue), the jump in cash returned may be exaggerated in this graph, because we are not netting out stock issues made by US companies in each year. This is a reasonable point, and I have brought in the stock issuances each year, to compute a net cash return each year (dividends + buybacks - stock issues) to contrast with the gross cash return (dividends + buybacks).

|

| Gross cash (Dividends+Buybacks) and Net Cash (Dividends+Buybacks-Stock Issues) as % of Market Cap |

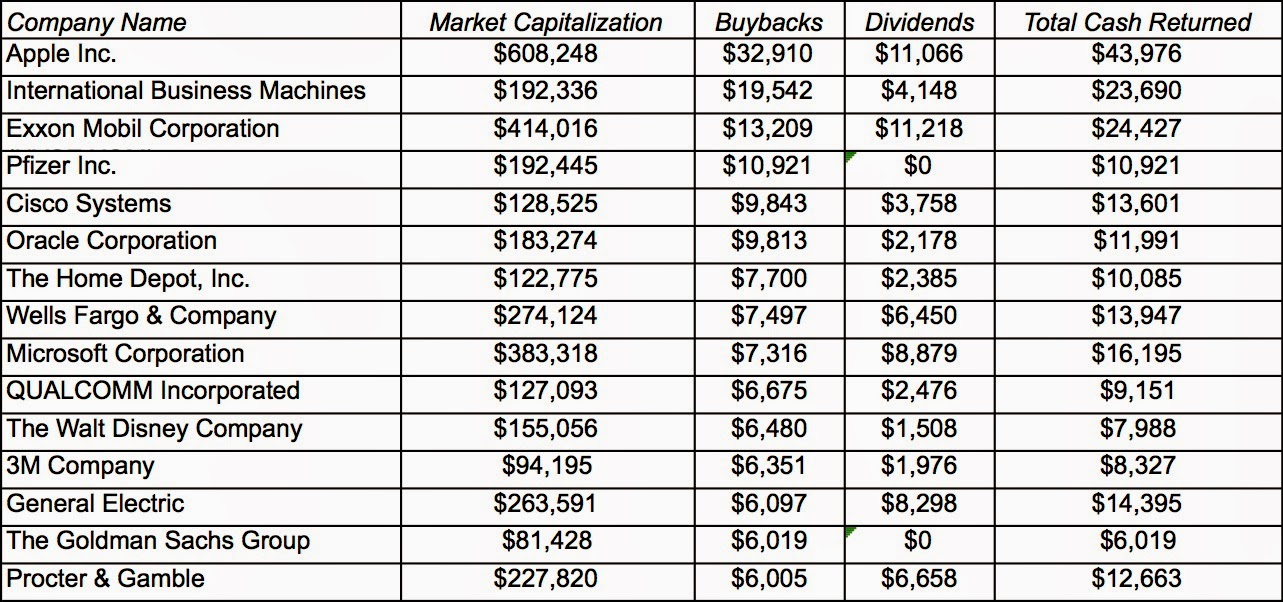

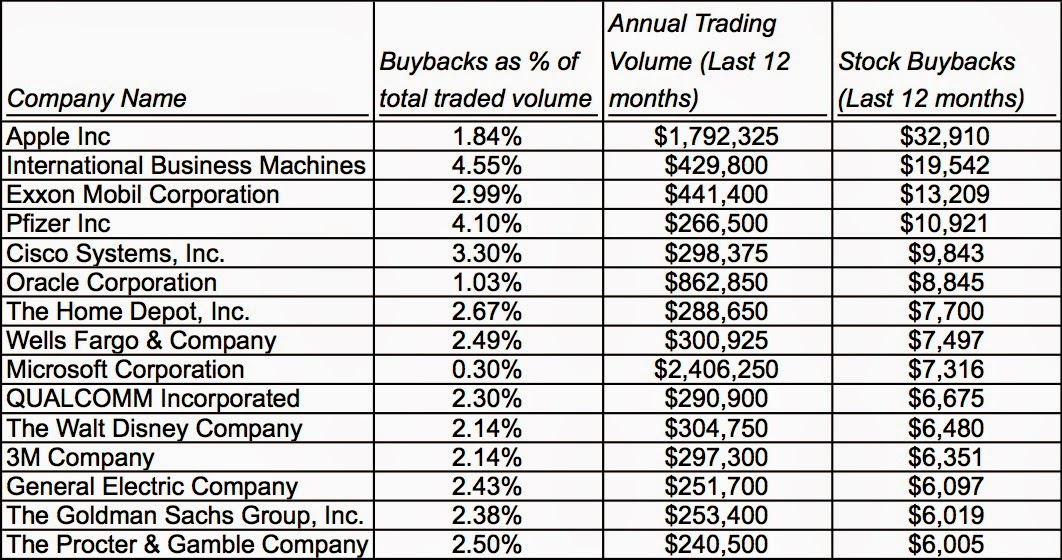

Since the aggregate values gloss over details, it is also worth noting who does the buybacks. It goes without saying that the largest buybacks (in dollar terms) are at the largest market cap companies, and the following is a list of the top fifteen companies buying back stock in 2013:

|

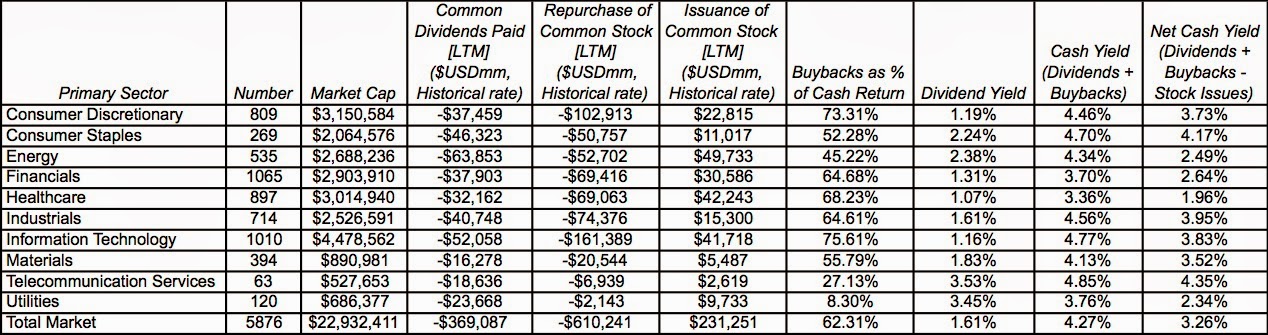

| Dividends and Buybacks in 2013: Data from S&P Capital IQ |

Other than utilities, the shift to dividends is clear in every other sector, with technology companies leading with almost 76% of cash returned taking the form of buybacks.

- Dividends are sticky, buybacks are not: With regular dividends, there is a tradition of maintaining or increasing dividends, a phenomenon referred to as sticky dividends. Thus, if you initiate or increase dividends, you are expected to continue to pay those dividends over time or face a market backlash. Stock buybacks don’t carry this legacy and companies can go from buying back billions of dollars worth of stock in one year to not buying back stock the next, without facing the same market reaction.

- Buybacks affect share count, dividends do not: When a company pays dividends, the share count is unaffected, but when it buys back shares, the share count decreases by the number of shares bought back. Consequently, share buybacks do alter the ownership structure of the firm, leaving those who do not sell their shares back with a larger share in a smaller company.

- Dividends return cash to all stockholders, buybacks only to the self-selected: When companies pay dividends, all stockholders get paid those dividends, whether they need or want the cash. Thus, it is a return of cash that all stockholders partake in, in proportion to their stockholding. In a stock buyback, only those stockholders who tender their shares back to the company get cash and the remaining stockholders get a larger proportional stake in the remaining firm. As we will see in the next section, this creates the possibility of wealth transfers from one group to the other, depending on the price paid on the buyback.

- Dividends and buybacks create different tax consequences: The tax laws may treat dividends and capital gains differently at the investor level. Since dividends are paid out to all stockholders, it will be treated as income in the year in which it is paid out and taxed accordingly; for instance, the US tax code treated it as ordinary income for much of the last century and it has been taxed at a dividend tax rate since 2003. A stock buyback has more subtle tax effects, since investors who tender their shares back in the buyback generally have to pay capital gains taxes on the transaction, but only if the buyback price exceeds the price they paid to acquire the shares. If the remaining shares go up in price, stockholders who do not tender their shares can defer their capital gains taxes until they do sell the shares.

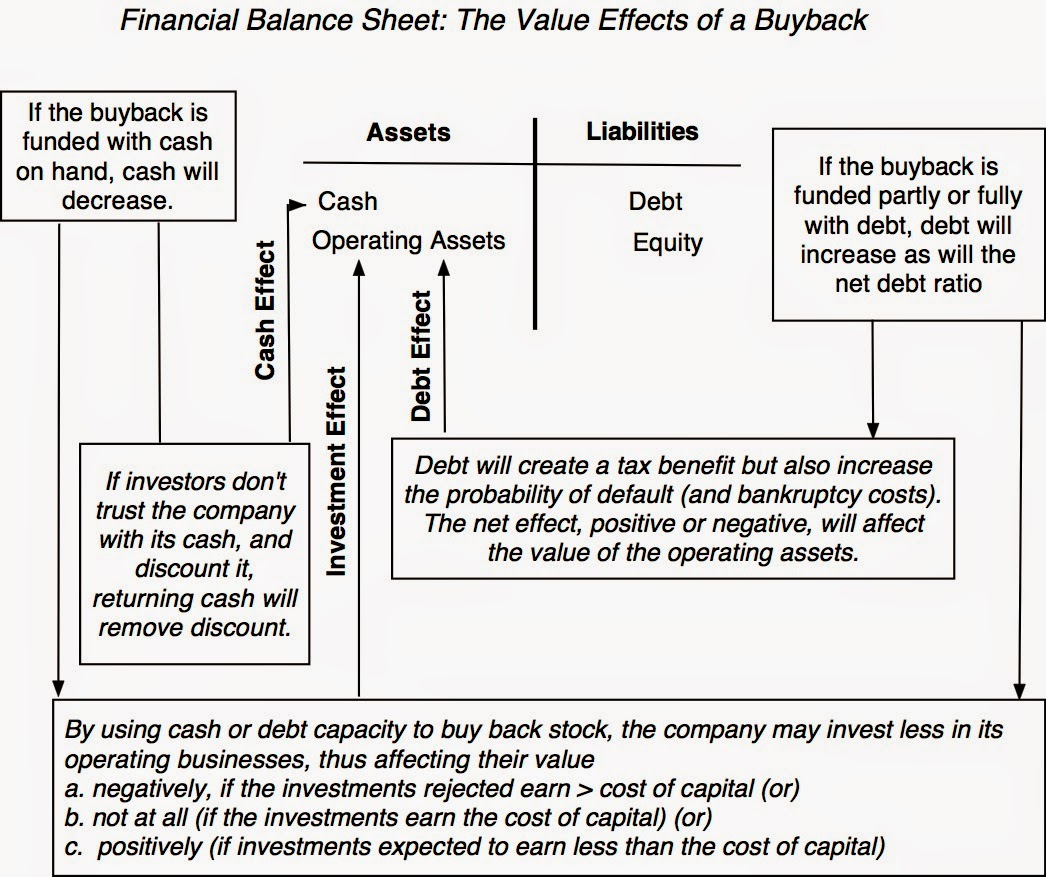

- Discounted cash holdings: There are some companies with significant cash balances, where investors do not trust the management of the company with their cash (given the track record of the company). Consequently, they discount the cash in the hands of the company, on the assumption that they will do something stupid, and this stupidity discount can be substantial. This is one of the few scenarios where a stock buyback, funded with cash, is an unalloyed plus for stockholders, since it eliminates the cash discount on the cash paid out to stockholders.

- Financial leverage effect: A firm that finances a buyback with debt, increasing its debt ratio, may end up with a lower cost of capital, if the tax benefits of debt are larger than the expected bankruptcy costs of that debt. That will occur only if the firm has debt capacity to begin with, but that lower cost of capital adds to the value of the operating assets, though it can be argued that it is less value enhancement and more of a value transfer (from taxpayers to stockholders).

- Poor investment choices: There is also the scenario where a firm that has been actively investing in a bad business or businesses (earning less than the cost of capital) redirects the cash towards buybacks. Here, less investment is value increasing and I will let you be the judge on how many firms on the top fifteen list in 2013 fall into that scenario. (I can think of quite a few...)

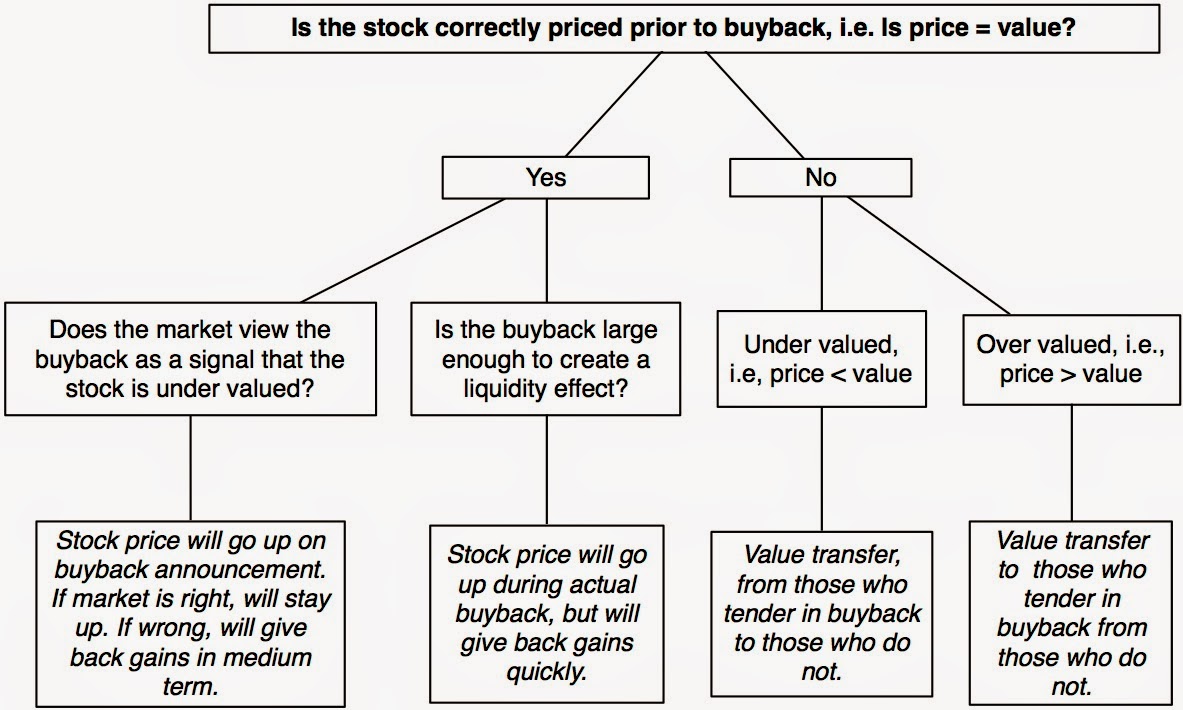

- Market mispricing: If the stock is mispriced before the buyback, the buyback can create a value transfer between those who tender their shares back in the buyback and those who remain as stockholders, with the direction of the transfer depending on whether the shares were over or under valued to begin with. If the price is less than the value, i.e., the stock is under priced, a buyback at the prevailing price will benefit the remaining shareholders, by letting them capture the difference but at the expense of the stockholders who chose to sell their shares back at the “low price”. In fact, it is likely that the market will view the announcement of the buyback as a signal that the stock is under valued and push the price impact in what is commonly categorized as a signaling effect. If the price is greater than the value, i.e., the stock is over priced, a buyback will benefit those who sell their shares back, again at the expense of those who hold on to their shares. In either case, there is no value creation but only a value transfer, from one group of stockholders in the company to another. Lest you feel qualms of sympathy for the losing group in either scenario, remember that most stockholders get a choice (to tender or hold on to the shares) and if they make the wrong choice, they have to live with the consequences.

- Signaling: For better or worse, markets read messages into actions and then translate them into price effects. Thus, when companies buy back stock, investors may consider this to be a signal that these companies view their stock to be under valued. If there is a signaling effect, you should expect to see the stock price jump on the announcement of the buyback and not the actual execution. The problem with this signaling story is that it attributes information and valuation skills to the management of the company that is buying back stock, that they do not possess. The evidence on whether companies time stock buybacks well, i.e., buy back their stock when it is cheap, is weak. While there is some evidence that companies that buy back their own stock outperform the market in the months after the buyback, there is also evidence that buybacks peak when markets are booming and lag in bear markets.

- Liquidity effects: A stock buyback, especially if it is of a large percentage of the outstanding shares, does create a liquidity effect, with the buy orders from the company pushing up the stock price. For this to occur, though, the shares bought back have to be a high percentage of the shares traded (not the shares outstanding). If there is a liquidity effect, you should expect to see the stock price rise around the actual buyback (and not the announcement) but that price effect should fade in the weeks after. While the Wall Street Journal makes legitimate points about how buybacks can sometimes tilt the liquidity playing field, looking across companies that buy back stock and scaling the buyback to the daily trading volume on the stock, the median value of buybacks as a percent of annual trading volume was 0.79% and the 75th percentile across all firms is 2.17%. It is true that there are firms like IBM and Pfizer that rank among the biggest buyback firms, where buybacks are a significant percentage of annual trading volume and there will be a liquidity effect at these companies, albeit short lived:

The Sum of the Effects

|

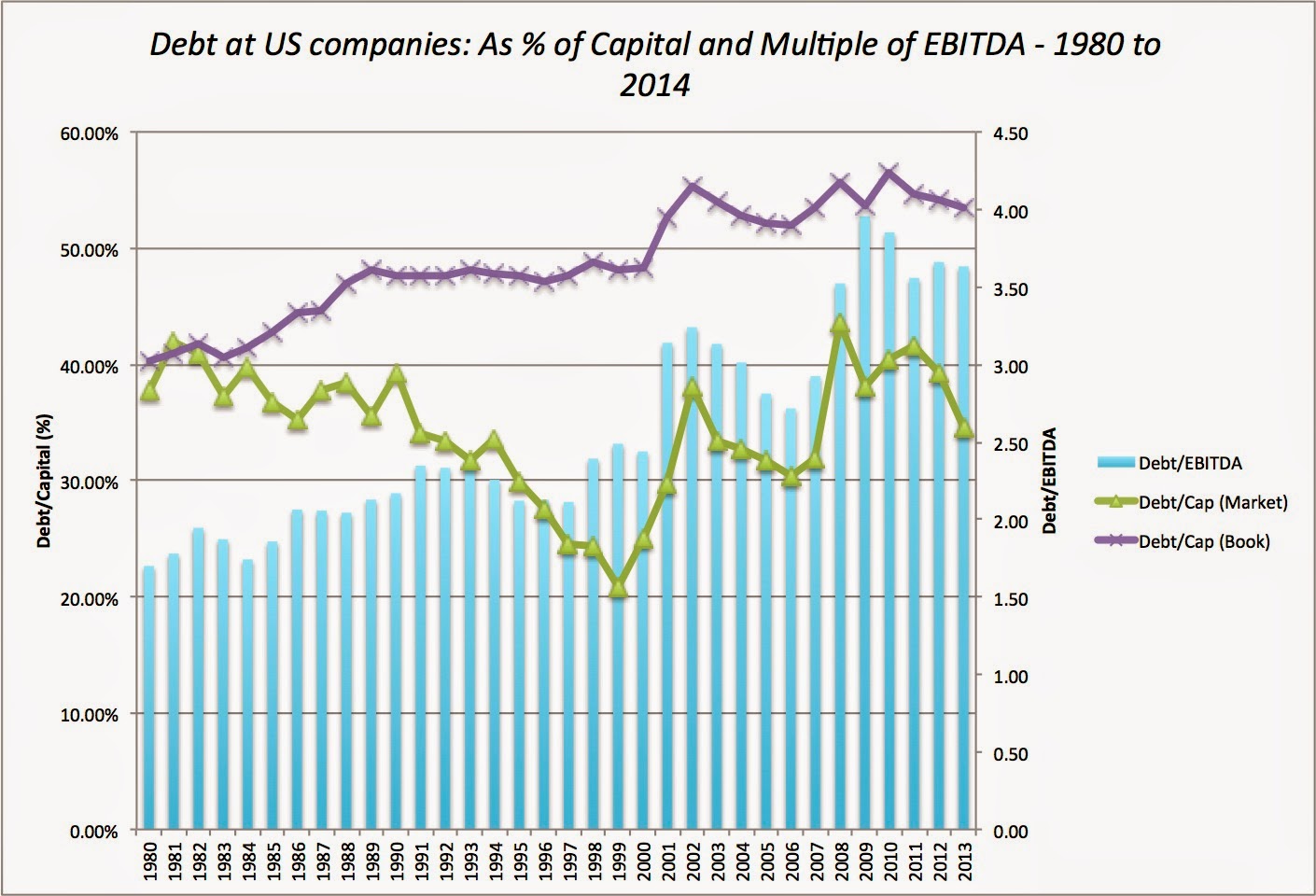

| Debt as % of capital & multiple of EBITDA: All US companies (Source: Compustat) |

It is true that overall financial leverage, at least as measured relative to book value and EBITDA has increased over time (though it has remained relatively stable, as a percent of market value). While this increase can be partially explained by decreasing interest rates over the period, it is worth asking whether buybacks were the driving force in the increased leverage. To answer this question, I compared the debt ratios of companies that bought back stock in 2013 to those that did not and there is nothing in the data that suggests that companies that do buybacks are funding them disproportionately with debt or becoming dangerously over levered.

| Data from 2013: Debt burdens at buyback versus no-buyback companies |

Companies that buy back stock had debt ratios that were roughly similar to those that don't buy back stock and much less debt, scaled to cash flows (EBITDA), and these debt ratios/multiples were computed after the buybacks.

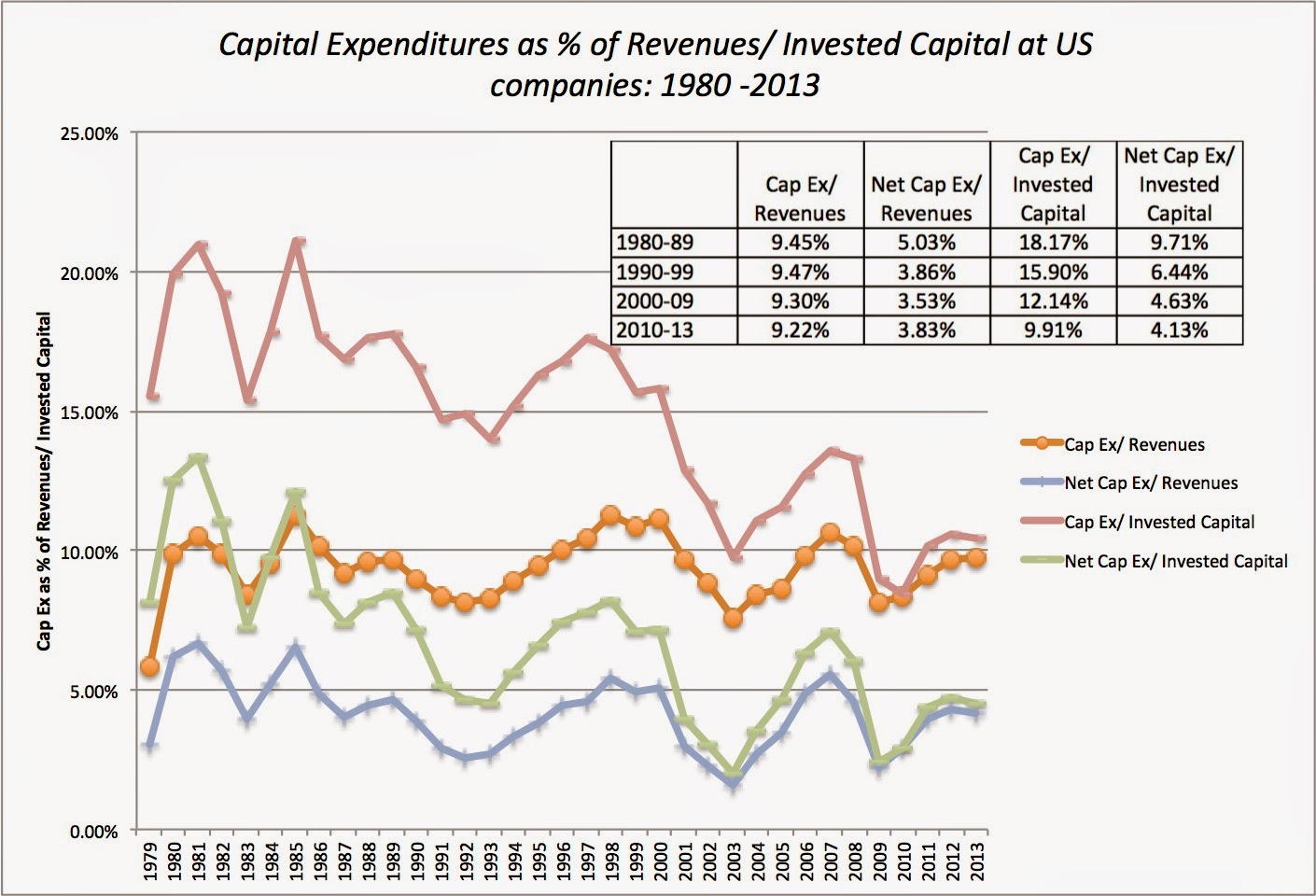

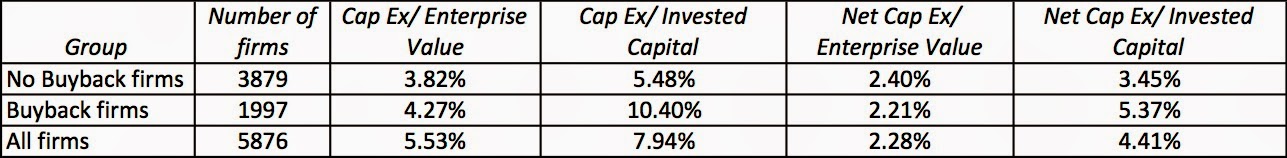

- The first is that there is little evidence that companies that buy back stock reduce their capital expenditures as a consequence. The table reports on the capital expenditures and net capital expenditures, as a percent of enterprise value and invested capital, at companies that buy back stock and contrasts them with those that do not, and finds that at least in 2013, companies that bought back stock had more capital expenditures, as a percent of invested capital and enterprise value. When you net depreciation from capital expenditures (net cap ex), the two groups reinvested similar amounts, as a percent of enterprise value), but the buyback group reinvested more as a percent of invested capital.

Capital Expenditures & Net Capital Expenditures = Capital Expenditures - Depreciation; US firms in 2013 - The second is that the cash that is paid out in buybacks does not disappear from the economy. It is true that some of it is used on conspicuous consumption, but that is good for the for the economy in the short term, and a great deal of it is redirected elsewhere in the market. In other words, much of the cash paid out by Exxon Mobil, Cisco and 3M was reinvested back into Tesla, Facebook and Netflix, a testimonial to the creative destruction that characterizes a healthy, capitalist economy.

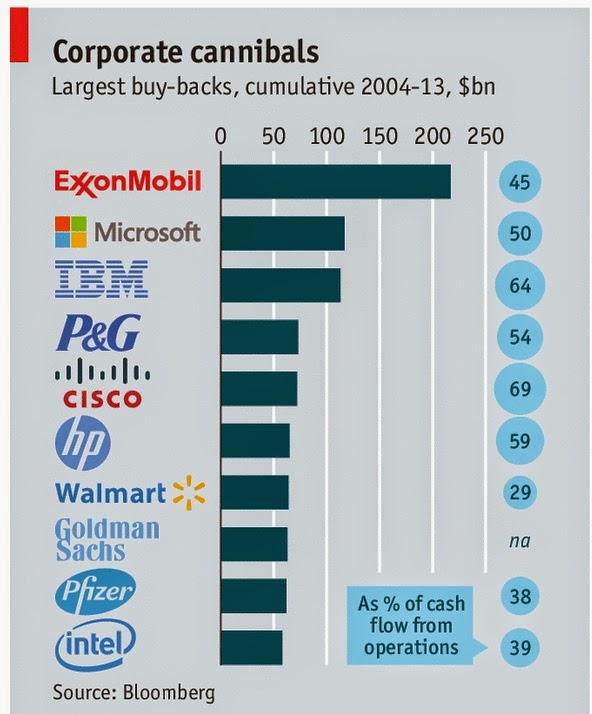

- The third is the notion that more reinvestment by a company is always better than less is absurd (unless you are a politician), especially if that reinvestment is in bad businesses. In the table below, I have listed the ten companies that were the biggest buyers of their own stock over the last decade (using the Economist's ill advised heading for those who buy back stocks):

There are two other issues brought up by critics of stock buybacks. One is that there is firms may buy back stock ahead of positive information announcements, and those investors who tender their shares in the buy back will lose out to those who do not. The other is that there is a tie to management compensation, where managers who are compensated with options may find it in their best interests to buy back stock rather than pay dividends; the former pushes up stock prices while the latter lowers them. Note that doing a buyback ahead of material information releases is already illegal, and any firm that does it is already breaking the law. As for management compensation, I agree that there is a problem, but buybacks are again a symptom, not a cause of the problem. In my view, it is poor corporate governance practice on the part of boards of directors to grant huge option packages to managers and then vote for buybacks designed to make managers even better off. Again, fixing buybacks does nothing to solve the underlying problem.

I think that both ends of the spectrum on buybacks are making too much of a simple cash-return phenomenon. To the boosters of buybacks as value creators, it is time for a reality check. Barring the one scenario where companies that buy back stock stop making value-destructive investments, almost every other positive story about buybacks is one about value transfers: from taxpayers to equity investors (when debt is used by an under levered firm to finance buybacks) and from one set of stockholders to another (when a company buys back under valued stock).

To those who argue that buybacks are destroying the US economy, I would suggest that you are using them as a vehicle for real concerns you have about the evolution of the US economy. Thus, if you are worried about insider trading, executive compensation, tax-motivated transactions and or under investment by the manufacturing sector, your fears may be well placed, but buybacks did not cause of these problems, and banning or regulating buybacks fall squarely in the feel-good but do-bad economic policy realm.

Is it possible that some companies that should not be buying back stock are doing so and potentially hurting investors? Of course! As someone who believes that corporate finance at many companies is governed by inertia (we buy back stock because that is what we have always done...) and me-too-ism (we buy back stock because every one else is doing it...), I agree that there are value destroying buybacks, but I also believe that collectively, buybacks make far more sense than dividends as a way of returning cash to equities. In the Economist article, I am quoted as saying that dividends are a throwback to the nineteenth century (not the twentieth), when stocks were offered as investment choices to investors who were more used to bonds and that fixed, regular dividends were designed to imitate coupons. Since equity is a residual claim, it is not only inconsistent to offer a fixed cash flow claim to its owners, but can lead (and has led) to unhealthy consequences for firms. In fact, I think firms are far more likely to become over levered and cut back on reinvestment, with regular dividends that they cannot afford to pay out, than with stock buybacks.