by Ben Carlson, A Wealth of Common Sense

When asked what people would learn from the financial crisis, GMO’s Jeremy Grantham replied:

In the short term a lot, in the medium term a little, the in the long term, nothing at all. That would be historical precedent.

As they say, we don’t want to let a crisis go to waste. Here are some enduring lessons we can all take away from a tumultuous period in the financial markets.

The Great Financial Crisis might be this generation’s Great Depression. I had a friend at a multi-billion dollar hedge fund that is very plugged in to the DC elites tell me to go to an ATM and take out as much cash as I could get after Lehman Brothers went under in the fall of 2008. It was a scary time. As George W. Bush said, “If money isn’t loosened up, this sucker could go down.” It almost did.

This period could shape our collective attitudes about risk for a long time to come.

Panicking is not a strategy. A portfolio without a disciplined plan is bound to lead to panicked buying and selling at the absolute worst times. This was a painful period for many investors because they panicked.

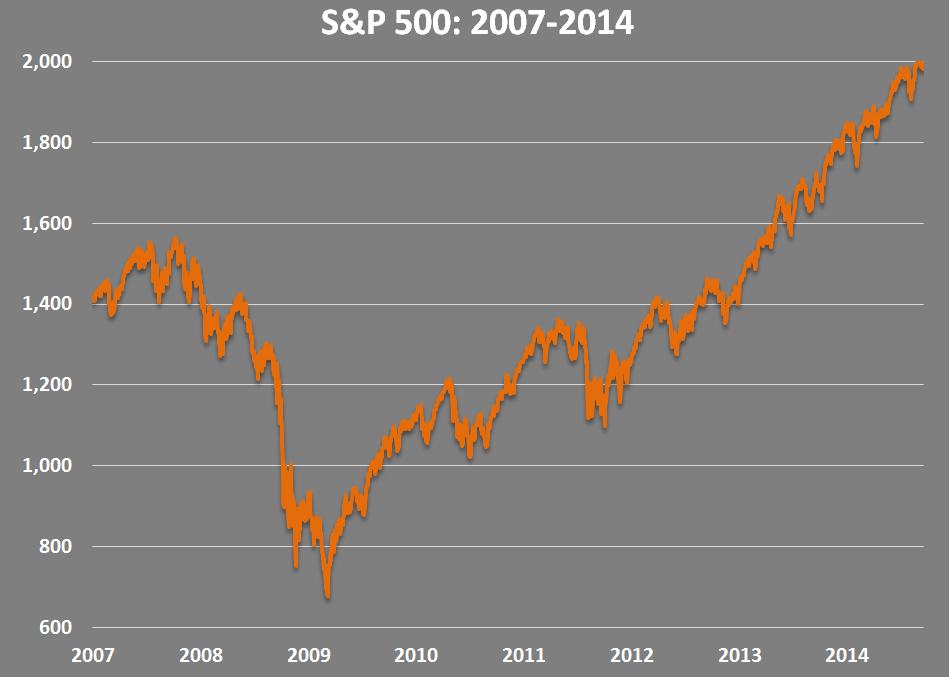

One of the few things you can count on with near certainty — markets are cyclical. See chart above.

Envy might be an investor’s worst enemy. We can’t stand missing out when everyone else is making money. It’s nearly impossible for investors to buy when everyone else is selling. Envy causes us to search for lottery tickets instead of investment plans. It makes us confuse our time horizons and risk profiles with other people’s. It makes us take on debt we can’t possibly pay back. And it causes booms and busts because we just can’t help ourselves.

The herd always piles in at the wrong time. I was talking to a guy in his 40s a few weeks ago and he shared his experience with the financial markets. He got into some mutual funds in the late-1990s. When that ended badly he took out all of his savings and eventually tried flipping houses in the mid-2000s. Once that fell apart he vowed to never invest again. It’s unfortunate, but I’m sure he’s not alone.

If you don’t understand it, don’t invest in it. This advice can help investors avoid the junky products pitched by Wall Street’s sales people when things get out of control in either direction, but it works as a good rule of thumb no matter where we are in the market cycle.

Understand your sources of financial advice. It’s easy to find advice from almost anyone these days. But 99% of the stuff you read or listen to will not have your interests or personal circumstances in mind. Many people took the wrong advice from the wrong source over the past cycle and it hasn’t worked out very well.

There’s no such thing as a bad investment, only a bad price. No security, sector, asset class or market is bulletproof. Safety is an illusion that’s often counter-intuitive. Bank stocks felt safe in 2007 because they had high dividend yields, but risky in 2009 after falling 70-90%. Any investment can become attractive at the right price or unattractive at the wrong price.

Main street is different from Wall Street. Waiting for “things to get better” in the economy before investing doesn’t work. There will never be a perfect time to take the plunge. The best time to invest is when you get your first paycheck (and then continue investing a piece of every paycheck after that).

Pessimism is easier to buy into that optimism. Fear sells and garners eyeballs from viewers, but over the long-term it’s a strategy for losers. As Charlie Munger once said, “Even if it works you’re a jerk.” There’s always an intellectual theory that sounds legitimate for a bold call like the dollar collapsing, hyperinflation or gold going to $5,000/oz. Following these types of bold predictions rarely works out well for investors.

It’s difficult to change your mind after making a correct market call. There were a number of very intelligent investors and economists that correctly foresaw the financial crisis and the ramifications of the real estate collapse. But a majority of them missed the ensuing recovery because they became so enamored with their initial call that it was impossible for them to change their mind. Overconfidence becomes a huge barrier for level-headed decisions once it sets in.

It’s OK to be wrong, just don’t stay wrong. A lack of humility and self-awareness has caused many market commentators to go from pundits to charlatans because they’re afraid to admit they were wrong and are too stubborn to face the facts. Everyone makes mistakes in the financial markets. It’s best to learn from them and move on.

Intelligence doesn’t always help in the markets. Some of the largest and most sophisticated funds in the world completely underestimated their tolerance for risk and portfolio exposures before, during and after the crash. These problems become magnified when trying to adjust on the fly and making decisions through the rear view mirror. Getting whipsawed by poorly timed portfolio moves is not something reserved for average 401(k) investors. Even professional investors fall prey to our most harmful cognitive biases to the detriment of their performance.

Investing is hard. It always looks easy with the benefit of hindsight, but at the time it never is because no one knows what’s going to happen. Billionaire hedge fund managers have had to close down their funds during both the crash and subsequent recovery because they couldn’t figure this market out. There were some that absolutely nailed the economic outlook but completely whiffed on the ramifications for the financial markets.

It’s OK to admit that it’s hard. Coming to this conclusion is the first step in becoming a better investor.

Now for the best stuff I’ve been reading this week:

- Josh Brown with 8 lessons learned from starting an investment firm (Reformed Broker)

- Coping with complexity (Stumbling and Mumbling)

- Why you’re being short-sighted with your pessimism (Andy Swan)

- Four simple steps for evaluating predictions (Above the Market)

- Be ready to accept big volatility if you want big returns (Irrelevant Investor)

- Lessons for young investors from Vanguard interns (Vanguard)

- Financial arguments stem from our different experiences in the markets (Morgan Housel)

- David Merkel with the most level-headed discussion on alternative investments I’ve read (Aleph Blog)

- Negative knowledge: How to throw away your money in 7 easy steps (WSJ)

Subscribe to receive email updates and my monthly newsletter by clicking here.

Follow me on Twitter: @awealthofcs

Copyright © A Wealth of Common Sense