by Cullen Roche, Pragmatic Capitalism

Okay, I am a little OCD so bear with me here. Actually, if you plan on reading any of my work in the future you’ll have to bear with me for 30-50 more years since I assume this sort of griping will be a persistent trend given how badly I think the worlds of modern econ and finance have been mangled by politically motivated theorists (assuming my OCD doesn’t kill me first)….

Anyhow, I was reading some more Burton Malkiel thinking on the markets when I came across this gem from 3 years ago. In this piece trashing US government bonds, Malkiel does something very strange. He makes the argument that dividend paying stocks are a good substitute for bonds. Now, I’ve seen this argument a lot over the years and we have to be VERY clear about something:

DIVIDEND PAYING STOCKS ARE NOT A SAFE SUBSTITUTE FOR BONDS! EVER! EVER!

Did I write that big enough? Maybe not. Let’s try again:

DIVIDEND PAYING STOCKS ARE NOT A SAFE SUBSTITUTE FOR BONDS! EVER! EVER!

Okay, you get my point. Of course, saying it isn’t enough. There should be some empirical data to back up this assertion. First, a bear market in bonds is nothing like a bear market in stocks. When someone compares the two instruments it means there is a high likelihood that they don’t understand the capital structure very well and haven’t connected all the dots here. A fixed income instrument has several embedded safety components that make it entirely different from stocks:

- It’s higher in the liquidation chain.

- It pays a “fixed income” over the course of its life.

- If held to maturity fixed income pays you back at par.

- The duration on a fixed income instrument is generally shorter than that of common stock.

This explains why fixed income is inherently safer than common stock. We can see this in the performance data. Since 1928 the 10 year US Treasury note has been negative in just 14 calendar years. Those negative years averaged a -4.2% return. Stocks, on the other hand, have been negative in 24 of those calendar years and with an average decline of -13.6%. The worst calendar year decline in stocks was -43% while the worst calendar year decline in bonds was -11%. So it should be clear that a bear market in bonds is very different from a bear market in stocks.

But what about high dividend paying stocks? People often confuse dividends for making an equity instrument similar in some way to a fixed income instrument. This is completely wrong. An equity instrument that pays a dividend still lacks all of the aforementioned built-in safety components that differentiate fixed income from common stock. It just means the company pays a dividend stream (which isn’t actually fixed and can be revoked at any point as many people found out during the financial crisis).

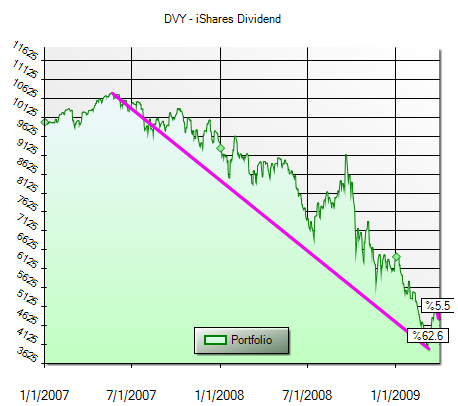

More importantly, dividend paying stocks can be atrocious performers at times. And it’s often because high dividend paying stocks are leveraged companies who borrow funds to finance dividends and operations. This was most obvious during the financial crisis. Take for instance, the iShares Dividend fund which cratered -62% during the financial crisis.

Going back to Malkiel though – I had to chuckle at this bit of “Random Walk” advice from 2011 when he recommend buying AT&T stock because it’s a high quality dividend paying stock:

“Another strategy would be to substitute a portfolio of blue-chip stocks with generous dividends for an equivalent high-quality U.S. bond portfolio. Many excellent U.S. common stocks have dividend yields that compare very favorably with the bonds issued by the same companies.

One example is AT&T. The dividends paid on the company’s stock result in yields close to 6%, almost double the yield on 10-year AT&T bonds. And AT&T has raised its dividend at a compound annual growth rate of 5% from 1985 to the present.”

Since then AT&T has generated a 36% total return. Not bad! Except for the fact that the high quality blue chip index of the S&P 500 has generated a 67% total return over the same period. In other words, Malkiel got trounced for engaging in the exact type of activity he mocked stock pickers for engaging in in this recent WealthFront blog post. The level of inconsistency and hypocrisy in some of this writing disturbs me, to say the least. One of the most influential thinkers in modern finance is just blatantly contradicting himself in these commentaries and yet people cite his work when it’s convenient to a certain perspective. That’s rubbish in my opinion.

Okay, I’ll lay off Malkiel now. But you should be starting to see a common thread in a lot of this work. There are disturbing inconsistencies and misunderstadings in the views and framework that a lot of this work is built on. And an entire industry has come to believe that this sort of thinking is a solid cornerstone for thought!

(pulls out hair)

Copyright © Pragmatic Capitalism