by Joseph G. Paul (pictured) and Greg Powell, AllianceBernstein

In a world of ultralow interest rates, the quest for income has left many investors stumped. Bonds are generally seen as more dependable sources of income than stocks. But our analysis suggests that income streams from equities are much more stable than widely believed.

On the surface, there are good reasons to consider equities for income. To start with, dividend yields on US stocks today are competitive with fixed-income yields. At the beginning of August, the trailing dividend yield on the S&P 500 was 1.8%, not far behind the 10-year Treasury yield of 2.6%. And the highest-yielding third of US stocks boasts a dividend yield of 3.0%. For simplicity, we’ll focus on Treasuries, as they’re generally the preferred choice for investors seeking safety.

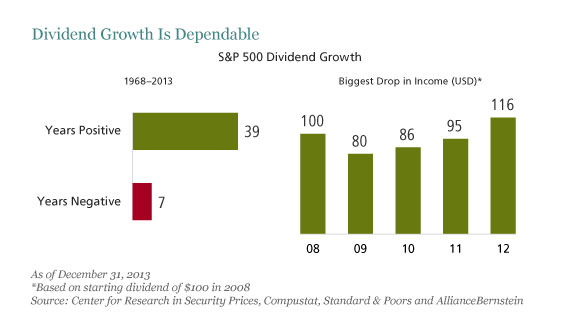

Dividend Growth Is Fairly Consistent

Dividends are actually more dependable than you might think. For the market as a whole, dividend growth was positive in 39 of the years from 1968 to 2013 (Display, left chart). Annual dividends only contracted during seven years. In the worst case, an investment producing $100 in dividends in 2008, as the global financial crisis struck, would slump to $80 of income in 2009 (Display, right chart). Yet by staying the course through 2012, annual income would be higher than the starting point.

How to Compare Stocks and Bonds

But can you really compare stocks and bonds? First, income streams from equities are generally seen as much more volatile than those delivered by bonds. Second, equity investors take a much bigger risk on their initial investment, while Treasury bond investors have always gotten their principal back.

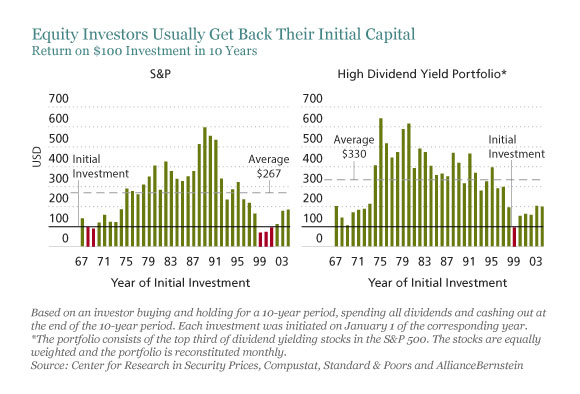

To test these issues, we looked at how an investor would fare by investing $100 in the S&P 500, holding it for 10 years, spending all the dividends and cashing out at the end. The same experiment was applied to a portfolio of the highest-yielding third of US stocks. Both analyses covered all rolling 10-year periods beginning in 1968 through 2004. In these examples, think about the initial equity investment like a bond’s principal, while the dividend income is like the coupon.

We found that the S&P 500’s average annual income over 10-year periods exceeded the income from the year before the starting point by 39%. For the highest-yielding stocks, that rose to 59%. In both, the average dividend income was always higher than the starting dividend income. This is never true for bonds, where the coupon is fixed.

Equity income grows consistently because many companies raise dividend payments per share on an annual basis. For example, Johnson & Johnson has raised its dividend for 51 straight years. Procter & Gamble has done the same for 58 years.

Today, payout ratios are extremely low. US companies are paying only about a third of their earnings as dividends, well below the long-term average. Many have record cash positions and solid balance sheets, so it’s easy to envision how dividends continue to grow.

Getting Back the Initial Investment

What about the initial investment? Treasury bond investors always get their principal back, while equity investors might suffer a loss.

In fact, in 87% of 10-year periods that we surveyed, investors in equities got their money back receiving, on average, more than twice as much (Display) from a $100 investment. The high-dividend-yield portfolio was even more stable than the market as a whole, only failing to recover the initial investment in one out of 38 10-year periods.

Of course, equity income has its risks. For example, if an investor needs to access the principal at some point during the decade, results can vary. Bonds carry interest-rate risk, but an investor can cash out at any time without putting too much principal in jeopardy. It’s riskier in equities because the value of the initial investment will fluctuate more, so getting out at the wrong point may lock in a loss.

As a result, an equity income approach is probably more appropriate for investors with long-term goals, who can put their money away for an extended period. In such cases, we believe that equity income can be a reliable substitute for part of a fixed-income allocation.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AllianceBernstein portfolio-management teams.

Joseph G. Paul and Greg Powell are portfolio managers of the AllianceBernstein US Equity Income fund (NYSE: AB).

Copyright © AllianceBernstein