by Mawer Investment Management, via The Art of Boring Blog

“Here,” I said, pointing to nowhere in particular. “Eleven o’clock.” I looked into the big, brown eyes of my driver and searched for some sign he understood my request. Nothing. He stared back blankly and then…smiled? This completely confused me. Had he understood my request? Or did he simply have empathy for my obvious frustration, which was manifesting in abnormally large hand gestures and an obsessive compulsion to check my phone? I had no clue, but it seemed my driver was perfectly satisfied with this exchange—he turned around, a smile still on his face.

My driver and I had spent the last two days navigating the streets of Bangkok in a sedan. He was driving me to my business meetings and I was attempting to get to them on time, which was no small feat given the chaotic traffic in Bangkok. Our efforts were rendered vastly more difficult by a severe language gap: he spoke no more than five words of English; my Thai was worse. It was a painful reminder of the value of sharing a common language.

When we reflect on the challenges of language, scenarios like my Thai business trip often come to mind. We think of the barriers of communication that exist between languages; less attention is paid to the choices made within a language, such as the use of certain words or frameworks. Yet these choices can greatly impact a team’s overall effectiveness.

Just how important is a common language to investing? While some investors view it as the sort of soft, fluffy stuff best left to liberal arts majors, empirically—and in our experience— it is an essential feature of high performing investment teams. A team’s use of language can have a significant impact on cognitive bias, team candour, quality of debate, speed of information processing and overall decision-making. This matters because the chief challenge of any investor is to get as close as possible to the truth, and ignorance of language and its influence increases the likelihood of bias and delusion. When we improve our language skills, we improve the quality of our decision-making.

The Power of Language

There is an iconic story in the advertising world, usually attributed to legendary copywriter David Ogilvy, about a man and his impact on a blind beggar. One day, a copywriter passes by a blind man who is holding a sign: I am blind. Instead of making a donation to the beggar, the copywriter writes something on the sign and moves on, returning later that day to find the man’s cup filled with donations. What did he write that prompted such a change? He had simply edited the sign to read: It is spring, and I am blind. In doing so, he transformed the sign from a plea for aid into a story of being deprived of the beautiful sensations of spring…and readers empathized.

It is remarkable how humans can convey highly complex ideas through exact sequences of sounds, and it is even more remarkable how much expressive power that affords. With a selection of words I can make your brain conjure an image of my choice: try NOT to imagine Marilyn Monroe riding a pink polar bear now that you’ve read it. Moreover, a carefully selected word evokes not only a single thought but an entire host of emotions and memories. This is why marketers love the story of the copywriter and the blind man: the influence of language is obvious.

Language is both powerful and dangerous. As a tool, language is neither inherently good nor bad, but can be commandeered for either altruistic or malevolent intent. This is obvious in virtually every conflict and war. After the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s, whether the opposing Nationalists were labelled “Rebels” or “Freedom Fighters” depended largely on your political viewpoint. In the Rwandan Genocide in 1994, the governing Hutu majority famously used words such as cockroaches to incite violence against the minority Tutsis.1 Of course, most examples are not so extreme. When management teams create presentations for investors, you can expect them to select words that convey a positive image, such as success, action, or improvement. We have yet to see a PowerPoint slide titled: Abysmal Failure.

Yet Machiavellian intentions are not necessary for word choice to matter. Even in the complete absence of intent, the selection of words, their connotations, and how they are strung together, counts.

Avoiding Brain Ninjas and Cognitive Bias

If you ever find yourself drinking at a bar and meet a linguist, never ask him or her if language shapes thought, unless you are prepared to buy several more rounds of drinks. To those who study the science of language, linguistic relativity is the centre of a hotly contested debate which began in the 19th century with the works of American linguist Edward Sapir and was later furthered by his student Benjamin Lee Whorf. These men argued that speakers of different languages may think and experience the world differently. Most notably, Whorf postulated that the Hopi, a Native American tribe, conceptualized time differently because of the structure of Hopi grammar. Although Whorf’s argument was eventually discredited, the myth that somehow an idea cannot exist without a corresponding word seems to have stuck around.2

We now know that it is possible to think of something without having a word for it.3 However, studies have shown that language has a way of shaping thought, mostly by influencing our interpretation of the world and how a person considers an idea. For example, studies have shown that in cultures with no word for left or right, and that only use the cardinal directions of North, West, South and East, people are more likely to stay oriented (i.e., not get lost).4 Researchers have also found that those who speak languages that attribute genders to nouns tend to associate masculine or feminine qualities to inanimate objects. Spanish speakers, for example, describe bridges as “big, dangerous, long, strong, sturdy and towering,” while German speakers view bridges as “beautiful, elegant, fragile, peaceful and pretty.”5 Anecdotally, my German colleague, Christian Deckart, insists that the prospect of going to the mall with his wife sounds distinctively more appealing in English than in German.6

For investors, it is important to understand how words shape decision-making through framing. Framing bias is the tendency for people to make different choices depending on how a scenario is presented (the “frame”) to him or her. As an example, a father with career aspirations for his son might ask him:

“What kind of doctor do you want to be when you grow up?”

Instead of:

“What would you like to be when you grow up?”

In this way, the father is attempting to control the outcome (his son becoming a doctor) by intentionally framing the question in a narrow way.

Investors are often impacted by framing because individuals react differently to the perception of gain than the perception of loss. As Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman highlight in their work, people are so sensitive to the perception of loss that they will irrationally favour one scenario over another, even if the final outcome is the same.7

For example, imagine that your uncle goes to a casino. He wins $50 in a single hand of blackjack and leaves. The next day, he returns to the casino to play blackjack, except this time, he wins $100 in his first hand and then loses $50 in the second. Again, he leaves with $50 in his pocket.

If your uncle was a rational man, he would be equally happy with either scenario. But according to Tversky and Kahneman, your uncle is likely to be happier in the first scenario where there was only one gain. This is because humans experience the emotional impact of a loss far stronger than they do a gain and your uncle probably viewed the fall from $100 to $50 as a loss. Never mind that the final outcome was exactly the same. If he perceived a gain in the first game and a loss in the second, he will view the first game’s result more favourably.

Because framing can have a strong impact on perceptions, investors must be aware of their language choices. Words have the potential to skew conversations and increase cognitive bias – a flaw in judgment due to filtering information through one’s own preferences and experiences.

Example:

|

Biased Statements |

Impact of the Skew |

|

“I am guilty of not putting enough growth into the model and therefore did not buy more stock when I should have.” |

The word “guilty” carries a strong negative association that is likely to skew the opinions within a group towards putting more growth into valuation models. Statements like this are common in bull markets when short-term market movements “teach” investors that they “should” be more aggressive and less strict on valuation. The opposite occurs in a bear market. |

|

Biased Statements |

Impact of the Skew |

|

“Management is excellent and only a complete idiot would miss this opportunity.” |

The potential investment is framed as an opportunity (positive) and there is social pressure created by labelling anyone who does not conform to the belief an idiot. Calling management excellent is also skewing the conversation by using a judgment instead of a fact. |

Framing explains why some sales agents and friends can seem like Brain Ninjas, hacking your emotions and guiding you towards their viewpoint, often without you even realizing it. Ever been in a relationship where your significant other appeared to win every argument? Most likely, you were in the presence of a Brain Ninja. Bought something you didn’t need because you liked the sa les person? Brain Ninja.

The power of the Brain Ninja increases with the speaker’s authority. According to the theory of Authority Bias, people have the tendency to be more trusting of those perceived as experts. This means investors must not only be aware of skewing conversations themselves, they must also be aware of the ways their opinions may be skewed by others.

Are you crazy? The Importance of Language Neutrality

Language is almost never neutral. Even when we attempt to present something neutrally, we probably do not. This is because we are often unaware of our own prejudices and the particular words that will evoke strong responses from others. There are, nevertheless,

techniques that can improve our ability to foster neutrality in our communications. Neutrality enables more effective decision-making on teams—a condition we believe is necessary for excellent, long-term investment performance.

Few have grappled with this idea more than Jim Ware, the Managing Director at Focus Consulting Group. A former Portfolio Manager at Allstate and a CFA charterholder with an MBA in finance, Ware now works with investment teams on building cultures that enable highly effective decision-making. Not only has his team seen the gamut of good and bad cultures within investment teams, they are responsible for producing thought-provoking articles such as “Does a Culture of Blame Predict Poor Performance for Asset Managers” and “Taking Emotions Out of Investment Decisions.”

Ware believes the choice of language within a team leads to high quality debate (or not). His team’s research has found that high quality debate is more likely to be accomplished when non-defensive language is used, which fundamentally demonstrates respect and

intimates an underlying acknowledgment that no one has a lock on knowledge. Unfortunately, these ideas are anathema to many of the big ego cultures of Wall Street where “how could you believe that?” or “why are you so stupid?” are the highly loaded questions more likely to be heard than the much less defensively phrased, “I observed the following…”

How pervasive is biased language in investment management? In Focus Consulting’s experience, very. This is problematic because if everyone clings to their own beliefs and no one shares information because they fear looking stupid, a culture can develop in which candour is limited.

Pars Pro Toto and the weighting problem of verbal language

Imagine that you are looking at a prospective investment. The company has an excellent business model, operates within a stable industry, generates returns over its cost of capital, and looks to be trading at an attractive valuation. You are keen to buy some stock—until you realize that the founder routinely awards himself a huge bonus and has the habit of buying Ferraris. What do you do? Should one fact be enough to discredit the rest of the investment thesis? Or is this fact balanced by the others? How do you go about weighing the facts against one another in your analysis?

This is a typical situation faced by investors and many would simply pass on the opportunity. However, an investor who let the Ferraris sway her opinion would be falling victim to the pars pro toto fallacy.

Pars pro toto is a Latin phrase which states that the part is the whole. If you were to stick your finger in the air in one spot of the room, and then conclude that the rest of the room is the same temperature, you would be invoking pars pro toto. In statistical terms, pars pro toto is akin to having a sample set of one and believing it represents the entire population. Sometimes this makes sense, such as in the case of room temperature, and often it does not, like when you are making an assessment of an individual’s entire personality from one interview.

Investors sometimes face a pars pro toto problem because of the nature of language. This is because language has an inherent weighting problem. That is, its structure does not always easily allow people to weigh one fact versus another. As an example, it is easy to understand that 50 kilograms is greater than 40 kilograms. But how do you compare two different management teams that are both described as “good” but for different reasons? What makes one company “great” and another merely “good”? Making comparisons with language is not as easy as with numbers.

The weighting problem in language encourages investors to adopt tools and frameworks to help them evaluate the facts in a given situation. Frameworks are useful because they can help investors analyze various facts, avoid the language weighting problem, and speed up the overall decision process. If used frequently, these tools even become part of the common language of the group, facilitating discussion and taking on commonly understood meanings.

One such tool that we have developed internally at Mawer is what we call The Matrix.

The Matrix

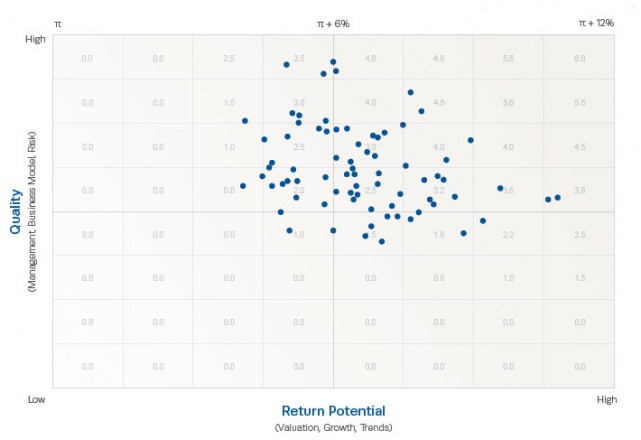

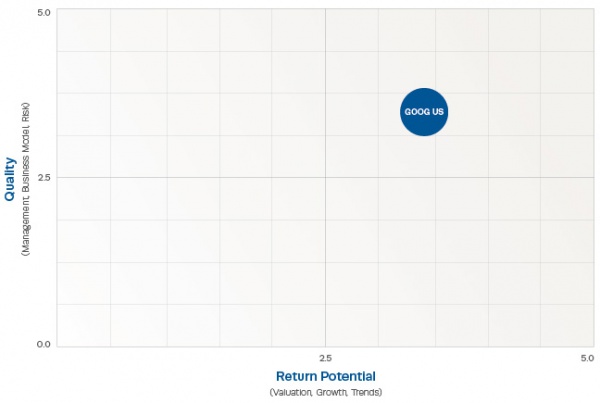

At its core, the matrix is a simple tool that allows our team to discuss the relative attractiveness of new and existing stock holdings without falling victim to the weighting problem of language. The horizontal axis grades the company on its return potential, while the vertical axis grades the company on its quality. As a result, every company that we look at gets plotted somewhere on the chart. This allows our team to debate an investment with greater understanding of each other’s viewpoints and compare it to other investments.

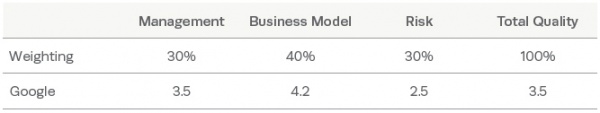

Imagine that an analyst and a portfolio manager are reviewing Google. The analyst believes that Google’s market position in online search is a near monopoly and that the company should therefore have a competitive advantage that is sustainable, allowing it to generate attractive returns for long periods of time. This same analyst has a favourable view of management because of the company’s impressive culture of innovation. They view the risk to the business and the industry as low.

Using the matrix, this analyst would rank Google favourably on the quality axis. This might look like the following (out of five, where five is top marks):

Quality Evaluation

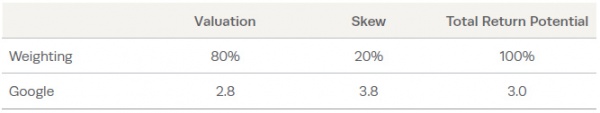

The analyst would also do valuation work, which would include a review of the historical financials, a full discounted cash flow, some forensic accounting and a few back-of-the-napkin calculations. The analyst might then believe that Google, at $566, is most likely trading within its fair value range of $450 to $700, with the potential skew to the upside if some of its current projects pan out.

They may then rank Google on the return potential axis as follows (out of five, where five is top marks):

Return Potential Evaluation

Plugging these inputs into the matrix, Google would land in the upper right hand corner of the chart: an attractive area where quality and return potential are high.

This is where the strength of the matrix comes in. The analyst is able to convey thorough and complex work in one simple visual. This allows the analyst and the portfolio manager to debate the company with a higher level of mutual understanding.

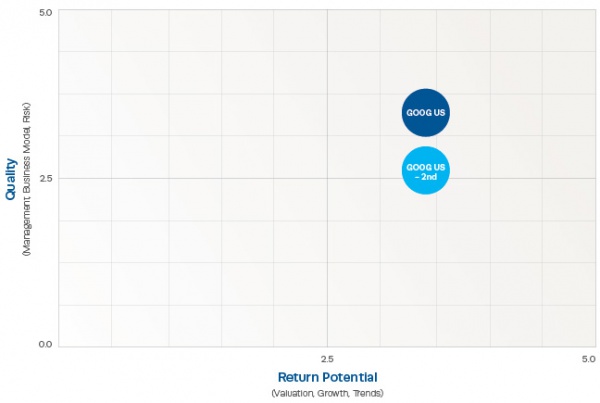

For example, let’s say that the portfolio manager basically agrees with the analyst’s valuation assessment but disagrees with the analyst in terms of management and risk. Given Google’s unusual approach to capital allocation, the portfolio manager believes that management is less likely to maximize shareholder value and gives them a lower grade. They also believe this creates many risks to the investment. This opinion would feed into the matrix, which would result in plotting Google less attractively on the quality axis.

This clear visual difference of opinion allows the analyst and the portfolio manager to have a finer, more relevant debate.

Although this is just a high level snapshot of the matrix, it provides an example of how tools can help address language’s weighting problem and how a common platform for debate can be created. In practice, our team uses the matrix to plot and compare entire portfolios against one another and against themselves over time. It has become part of our common language, in the same way that phrases like competitive advantage, return on capital and economic moat have become part of the financial industry’s vocabulary. The benefit has been clarity, stronger mutual understanding and the ability to process complex viewpoints faster.

Of course, investors must be careful not to treat tools like this as “the answer.” Just like our discounted cash flow models, the matrix is a blunt instrument that, at best, helps us get closer to an objective reality. It is not meant to be a definitive answer, rather a tool to foster more productive conversations.

The Art of Building a Common Language

Every group has the opportunity to proactively build a common language. Language can be shaped to enhance culture and improve decision-making or it can be left to evolve of its own accord. What matters is that a team understands its goals, the culture it wants to create, and the role that language can play in these endeavours.

The following are strategies that we have found successful in creating a platform for common language:

1. Be extremely clear in differentiating between fact and judgment.

Separating statements of fact from statements of opinion can help team members more efficiently identify any items that may need debating. For example, the fact that Google has over 670 million outstanding shares does not need debating.

Stating that Google has a strong management team is a judgment that may need further clarification or debate.

2. Observations are typically better received than statements of advice or assessment.

Feedback can be like opening a can of worms for a team. Our team focuses on statements of observation such as “I observe that you said ‘um’ five times in your presentation,” rather than statements of assessment like “your presentation was ineffective,” or statements of advice like “you should say ‘um’ less.”

In general, we find that statements beginning with “I observe…” are easier to receive than those that begin with “I think/you should ...” because the judgment is eliminated. We find this type of feedback more valuable because defensiveness is considerably reduced thereby allowing the recipient to focus on the data provided.

3. Tools and frameworks are useful but they are, at best, blunt instruments and should never be confused for the “answer.”

Tools and frameworks can help foster more productive communication, but they should be used in congruence with a comprehensive and logical process; that is, they are one useful component within a larger underlying system.

4. Brevity is underrated.

5. Always adopt a skeptical mindset. Be vigilant against framing.

It is amazing how few facts turn out to be truths. One of the lessons we are frequently reminded of is the importance of seeking different, objective sources of information when examining a potential investment. Management teams are

incentivized to give you a biased answer and will outright lie or deflect you from the truth at times. Speaking to customers, suppliers and competitors and otherwise conducting what investor Philip Fisher calls “scuttlebutt,” is absolutely critical.

6. Define common terms for increased clarity.

Take time to provide clear definitions for the important words on your team.

For investors, this list might include risk, competitive advantage, or a good management team. A common language requires that everyone understands what each term means.

No matter how hard a team tries, it will never fully shed the biases inherent in language. Members can never be perfectly brief, clear or neutral, even if they invest a massive effort into these goals. But if perfection is beyond us, excellence is not. Teams can be transformed by simple improvements in language— something our research team understands very well, as we have made considerable strides in this area over the last decade. By improving our understanding and application of language, we endeavour to improve our candour, decision- making, debate and collaboration.

Words are never just words. Language matters.

1 See Romeo Dallaire’s Shake Hands with the Devil: The failure of Humanity in Rwanda for a chilling account of this tragedy.

2 Most famously depicted in George Orwell’s dystopian novel, 1984, in which the government bans subversive words in an attempt to make them unthinkable.

3 Steven Pinker’s "Big Think Video: Linguistics as a Window to Understanding the Brain" is a good introduction to the concepts of non-linguistic thinking.

4 Boroditsky, Lera. “How Language Shapes Thought: The languages we speak affect our perceptions of the world.” Scientific American Feb. 2011: 63-65.

5 Schmidt, Lauren, and Webb Phillips. “Sex, Syntax and Semantics” in Language in Mind: Advances in the Study of Language and Thought, edited by Dedre Gentner and Susan Goldin-Meadow. Massachusetts Institute of Technology: 2003.

6 As Christian explains, in English, the phrase “taking a trip to the mall” incorporates the idea that there will be activities to do there, which makes the “trip” a viable alternative to other activities, such as going to the movies or watching hockey. In German, “Wir gehen ins Einkaufszentrum” basically means “We need to go to a place that sells something which we need.”

7 Collectively called Prospect Theory, their discoveries not only illustrate how people behave differently given the words selected, but also debunk the myth in economics that people behave rationally.

This post was originally published at Mawer Investment Management