by James Picerno, Capital Spectator

Inflation is mounting a comeback. Not as an imminent macro threat, at least not yet. But as a topical subject for monetary policy and a relevant factor for looking ahead in economic and investment terms, the subject of inflation will likely resonate on a deeper level going forward. The source of this shift, of course, is the Federal Reserve, which is winding down its great experiment in monetary stimulus and laying the groundwork for reviving something approximating a “normal” policy regime.

The latest smoking gun was outlined in yesterday’s release of the Fed’s FOMC Minutes for last month’s meeting: “If the economy progresses about as the Committee expects, warranting reductions in the pace of purchases at each upcoming meeting, this final reduction would occur following the October meeting.” Although the guidance in that sentence wasn’t unexpected, what’s different is that the central bank is now publicly discussing explicit dates as opposed to vague references about the future. A minor change? Perhaps, although one can persuasively argue that the shift marks a new stage in the Fed’s game plan in the post-2008 world.

Nothing’s written in stone, of course, even when the Fed cites specific dates. But barring a sudden and expected deterioration in the economic trend, which looks unlikely based on the latest data, we’re formally in the end game. Quantitative easing (QE), which was unveiled in its first incarnation in 2009, is headed for the history books, and it leaves a mixed legacy. The first question for the new era: When will the Fed start raising interest rates? That’s a ways off, expected to start sometime next year, or just after the new year. Depending on the forecast, the first increase in Fed funds will start as early as mid-2015 or as late as early 2016. In any case, no one should confuse the end of QE with higher rates. The former leads to the latter, eventually, but the two aspects of policy are different animals in terms of timing.

Again, there’s nothing shocking about the Fed’s latest statement, although it’s a relatively clear reminder that we’re finally moving away from the extraordinary phase of economic stimulus that was rolled out after the financial crisis of late-2008 that nearly triggered a full-scale meltdown in the capital markets and the economy. The process of returning to a normalized policy will remain gradual, but the Fed’s release of a hard date for ending QE is as good as any for marking the end of an era.

Now that we know when the bond-buying program will end, the markets will increasingly focus on when the first rate hike will arrive. There are multiple variables that will factor into this event, but the obvious place to start is with inflation as a signal for what’s coming and when. Although pricing pressures have been unusually low for most of the past five years, it’s reasonable to assume that the disinflation/deflation threat is retreating in a meaningful if still gradual degree. It could come rushing back tomorrow, of course, if an unexpected macro shock strikes. But let’s assume that moderate growth prevails, which is a realistic assumption at the moment. In that case, it’s time to start watching inflation on a deeper level—something we haven’t had to do over the last several years.

With that in mind, a few charts are worth your time for a quick update, starting with the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation via the personal consumption expenditures (PCE) price index that’s published monthly by the Bureau of Economic Analysis. As the latest Fed minutes advised, “U.S. consumer price inflation, as measured by the PCE price index, was about 1-1/2 percent over the 12 months ending in April, below the Committee’s longer-run objective of 2 percent.” Note that subsequent data released since the Fed’s June meeting show that headline PCE inflation is running a bit higher at 1.8% on a year-over-year basis through May—the highest since October 2012. Core-PCE inflation (excluding energy and food) is also turning up, advancing 1.5% for the year through May.

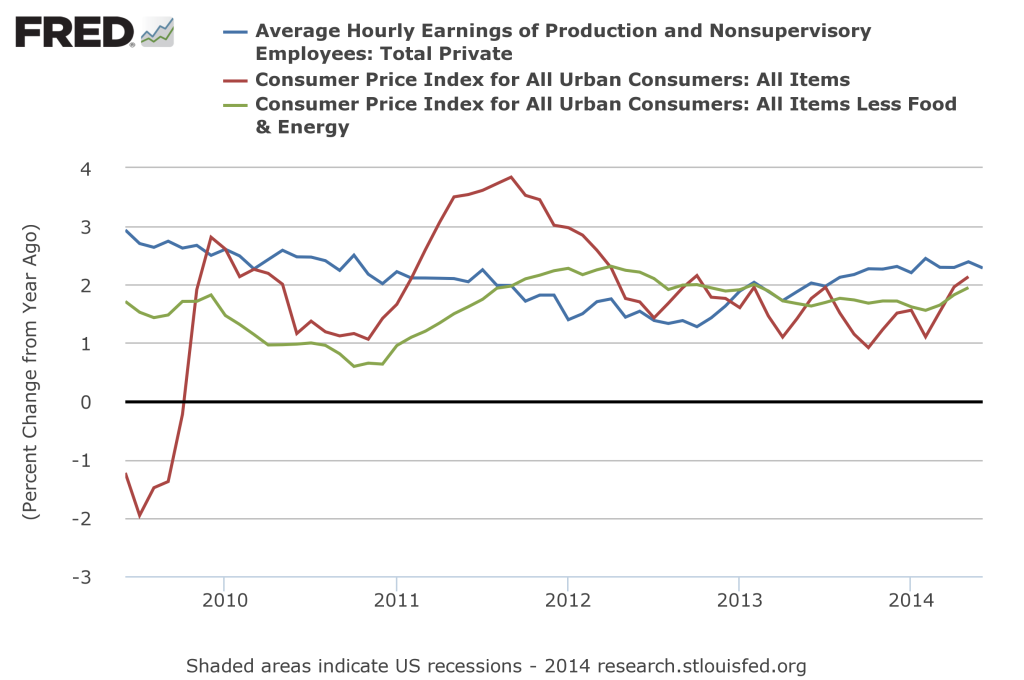

For another view of inflation, consider the widely cited Consumer Price Index, in headline and core terms. Both are inching upward, with headline CPI rising 2.1% for the year through May, which tracks the record for PCE inflation in reflecting the highest rate since October 2012. Core CPI inflation’s pace is rising as well, reaching 1.9% for the year through May, the most since February 2013. Wage inflation is even higher, although it’s been relatively stable. The average hourly earnings of production/nonsupervisory employees (a widely monitored benchmark for wage inflation) was higher in June by 2.3% vs. a year earlier, or roughly average relative to the annual trend in recent months.

Finally, a market-based forecast of inflation anticipates the consumer price index rising at around 2.3%, based on the yield spread on a 10-year nominal Treasury less its inflation-indexed counterpart. That’s about average relative to the range we’ve seen over the past five years, although it’s worth noting that a 2.3% inflation assumption by this definition is close to the highest so far in 2014.

Copyright © Capital Spectator