by James Picerno, Capital Spectator

Michael Edesess questions the notion of a “rebalancing bonus,” wondering if it’s a ghost in money management’s machine. The concept, he recaps, was formalized in Bill Bernstein’s influential 1996 study—“The Rebalancing Bonus: Theory and Practice”, which found that “the actual return of a rebalanced portfolio usually exceeds the expected return calculated from the weighted sum of the component expected returns.” Edesess points out, apparently with Bernstein’s support, that the 1996 analysis is slightly misleading in the sense that the underlying assumptions aren’t as practical as they could or should be. Although Edesess’s number crunching is yet another reminder that you can’t count on rebalancing to boost return, that’s still not an argument for shunning rebalancing as a risk-management tool.

Nonetheless, Edesess nails what I think is a critical issue on the topic of rebalancing, namely, recognizing that this technique requires us to navigate the rocky path between two of the most powerful forces in asset pricing: mean reversion and momentum. As he explains:

Furthermore, some studies, including particularly one for which I am grateful to Bernstein for supplying, have concluded that securities prices have historically had a tendency to mean-revert over time, with a half-life of about three and a half years (i.e., half of them mean-revert by that time). Other studies have shown that for shorter time intervals, securities prices show signs of mean-reversion’s opposite: momentum. That is, a high return over a time interval has increased the likelihood that the return will be higher than average over the next interval.

These results are in agreement with the theories of Hyman Minsky and behaviorists in finance and economics that, basically, irrational exuberance and panics do produce bubbles and crashes (i.e., momentum and mean-reversion, respectively).

However, even if these things are true, does that mean that rebalancing on any particular schedule will succeed? The rebalancing would have to occur at just the right time to catch a mean-reversion in order to succeed – and if rebalancing occurred when momentum was in charge, it might even be counterproductive.

Edesess runs some statistical tests of his own and finds that “introducing mean-reversion into the returns process did not cause rebalancing to beat buy-and-hold any more than it did when returns did not mean-revert.” It’s fair to say that when it comes to looking at rebalancing as a return-boosting technique, the best you can say is that the record is mixed. Much depends on the assets and time period under scrutiny, along with the details of the rebalancing strategy. Suffice to say, there’s a wide array of results. But there’s also a broad consensus: Just do it. Reviewing a number of studies on the subject in my book Dynamic Asset Allocation (see Chapter 6), I noted that there was disagreement about how and when to rebalance. Nonetheless, most analysts agreed that rebalancing as a strategy was likely to be superior to no rebalancing.

Edesess doesn’t necessarily disagree, although he argues (rather persuasively) that assuming that rebalancing will always generate a higher return is more about hope than facts:

Rebalancing is certainly not necessarily harmful, unless it conflicts with another risk management strategy that better suits the investor. It is better to have an investing discipline than not to have one, and rebalancing is one acceptable default discipline – especially when the investor would fail to adhere to any discipline if his portfolio’s volatility exceeded a particular level. It should not, however, be thought of as a strategy that delivers a returns bonus as compared to other strategies.

John Rekenthaler at Morningstar has read Edesess’s critique and decided that two essential lessons emerge in matters of rebalancing:

1) Rebalancing between assets with similar return levels brings a benefit (higher returns) without cost;

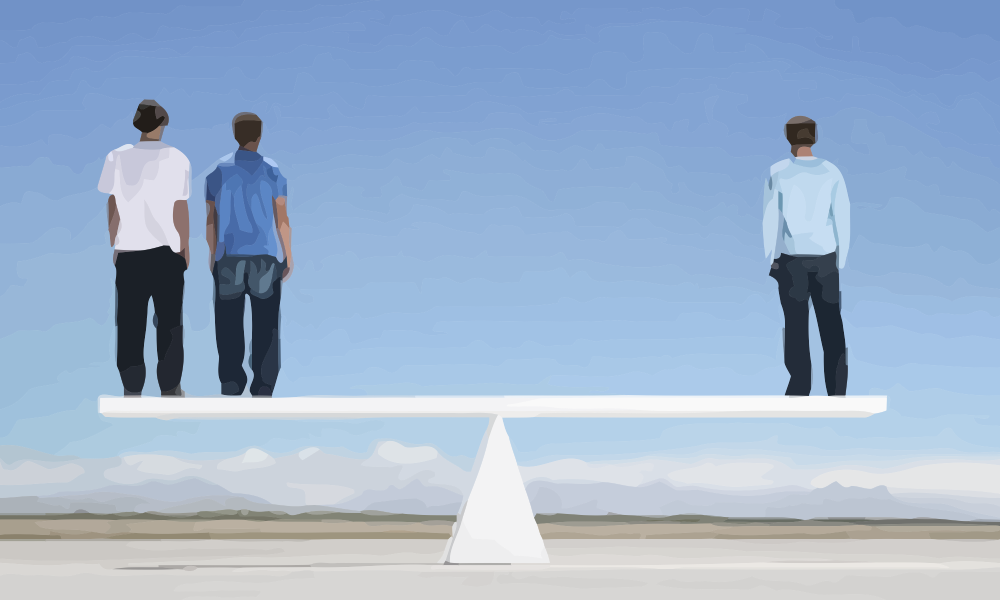

2) Rebalancing between assets with dissimilar return levels brings two benefits (maintaining portfolio risk level, participating in asset-class mean reversion) and one cost (ultimately lower returns due to owning more of a lower-performing asset).

Perhaps the most valuable point that Edesess makes is a reminder that any rebalancing analysis needs a robust benchmark. He recommends (and I agree) that “the only meaningful comparison is with a buy-and-hold strategy, i.e., a strategy of not rebalancing. The reason for choosing that benchmark is that it is the simplest and most straightforward alternative to rebalancing.”

By that standard, it’s not terribly difficult to find papers that offer encouragement for thinking that you might earn a rebalancing bonus. Meb Faber’s widely cited 2007 study (and an update in 2013), for instance, found that a simple strategy of tactical asset allocation across multiple asset classes based on moving averages juices returns and lowers risk vs. buying and holding. I’ve generated similar results with the rebalanced version of my Global Market Index compared with its unmanaged cousin (see here and here, for instance).

Can you count on earning a higher return with rebalancing? No. In fact, you can’t even count on reducing risk with rebalancing. That’s the nature of finance: there are no guarantees. But if you study history intelligently, you can learn a thing or two. That starts with a basic fact: if you don’t rebalance, you’re effectively letting Mr. Market run your asset allocation strategy, i.e., you’re favoring a market-value-weighted mix of assets.

You could do a lot worse. History suggests that passively holding a broad set of asset classes, weighted by relative market values, is competitive with most attempts to do better. But for reasons of risk management and/or earning something better, you have two basic choices if Mr. Market’s not your cup of tea (and he usually isn’t, based on choices in the real world).

First, you can alter his asset allocation: leave out this asset class, overweight that one, etc. Two, you can rebalance. Unless you go off the deep end on the first choice, which isn’t usually recommended, most of your success (or failure) will be bound up with rebalancing. The details surely matter. For most folks, the lesson is clear: some form of rebalancing is productive if only to keep the winners from dominating the asset allocation, which inevitably exposes you to painful short run volatility a la mean reversion. In fact, virtually everyone agrees. Rekenthaler sums it up rather well: “There is no rebalancing debate.”

There, is however, plenty of work to do to find an appropriate rebalancing strategy for each investor. It’s hard work because we’re all forced to make choices based on imperfect information due to a familiar gremlin: an uncertain future. In that sense, we can think of asset allocation and rebalancing as the worst set of tools available–except when compared with everything else. In any case, customization is crucial. Andre Perold and Bill Sharpe’s 1995 paper–“Dynamic Strategies for Asset Allocation”–remains the gold standard for summing up the critical challenge:

Ultimately, the issue concerns the preferences of the various parties that will bear the risk and/or enjoy the reward from investment. There is no reason to believe that any particular type of dynamic strategy is best for everyone (and, in fact, only buy-and-hold strategies could be followed by everyone). Financial analysts can help those affected by investment results understand the implications of various strategies, but they cannot and should not choose a strategy without substantial knowledge of the investor’s circumstances and desires.