by Mawer Investment Management, via The Art of Boring Blog

In the months since the news of the crisis in Ukraine first broke, media outlets have followed a conflict that has gone from an internal matter to one that is international in scope. Not only are Russia and the U.S. standing off, a number of Russian companies have been impacted by economic sanctions put in place by the U.S., Canada and the European Union. And like other politically charged events, coverage has not always been objective. Narratives have emerged that are highly skewed to the biases and interests of certain groups.

In North America, the narrative sounds something like this: Ukraine is being torn asunder from a tug-of-war between a progressive West and a corrupting Russia. It is a crisis that can be largely blamed on the ambitions of Russian President, Vladimir Putin, who, like a geopolitical playground bully, is trying to take things that don’t belong to him. According to this view, Russia is impeding on another nation’s sovereignty and undermining otherwise healthy economic relationships.

But recent conversations with a colleague, who happens to be both Russian and not overly fond of Putin, informed me of a different narrative. He provided me with translated notes of the address that Putin gave to parliament before they voted to accept Crimea as a Russian territory. In the address, Putin described how Crimea had been part of Russia for centuries, that separation had been against Russia’s will, and that more than 90% of the Russian people supported re-unification. If not wholly unexpected, these words were nevertheless informative. By annexing Crimea, Putin reversed his falling approval status and strengthened his domestic ratings. This was an angle that I had not yet seen in western media.

Clearly, the North American viewpoint has bias. Nevertheless, it appears to be the prevailing story in the West, which is important to recognize because there is risk in acting on a single story.

Consider, for example, a professional accounting company in which we used to hold a small position. This company had grown impressively through a series of small acquisitions and was selling the story of its role as a market consolidator.

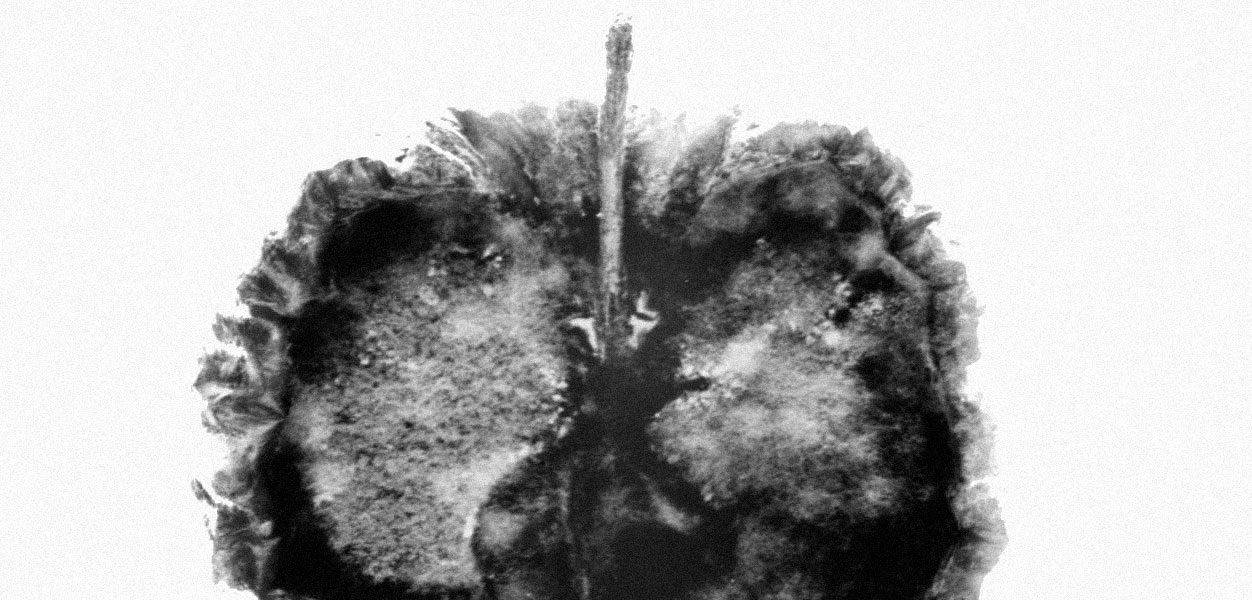

The CEO spoke eloquently of the firm’s culture and vision, and extolled the many benefits of its value proposition. It all sounded solid – but, unfortunately, it was an illusion. Like a shiny apple that is rotten on the inside, this company was masking weak growth in its existing businesses through acquisitions and was then failing spectacularly at integrating them. What virtues existed in the original business model became diluted through poorly conceived compensation plans, weak integration and overall bad management systems.

It took evidence outside of their management’s story for us to see what was really going on. Even if the headline numbers seemed reasonable, when you stripped the organic growth rate from the inorganic, something was off. Of course, management always offered plausible explanations; they could readily articulate why these were temporary aberrations and not symptoms of a more fundamental issue. We could have taken them at their word and trusted in this (single) story. Instead, we dug deeper and spoke to a firm that had called off a proposed merger with the company. According to this firm, the merger was called off because of strange inconsistencies in the financial projections and a level of turnover that was more than double the industry standard. That was enough for us to back off and we sold the rest of an already small position.

Investors must be wary of the danger in a single story. Just because you receive a signal does not mean it comes from a new source or that it is objective. As an investor, fresh signals are intermittent. It is far more common to hear the same tune played over and over, whether it comes from management teams or economic commentators. When evaluating macroeconomic situations, such as the Ukraine crisis, or choosing to invest in a company, it is imprudent to accept only one source of information. There is a reason why we comb through financial statements and attempt to speak with competitors, clients and customers before we invest in a company. Almost all information is biased in some way. Likewise, narratives are inherently biased. That doesn’t necessarily make them bad; it just means greater diligence must be taken to achieve an objective reality.

This post was originally published at Mawer Investment Management