by Daniel B. Eagan, AllianceBernstein

Dec 13, 2012

It’s easy to understand the allure of hedge funds—and the fear they inspire. After conducting rigorous research aimed at separating fact from hype, we have concluded that hedge funds historically have had an attractive risk/return profile.

We’ve also concluded that hedge funds pose risks that volatility doesn’t capture, but that a well-executed hedge-fund strategy could reduce the odds of large short-term losses in an investor’s overall portfolio.

The allure of hedge funds is simple: some legendary hedge-fund managers have delivered gross returns of 60% or more in some years. The fear has a simple explanation, as well: there have been spectacular blowups by a few hedge funds over the years. Nonetheless, widely cited databases show that hedge funds on average have provided higher returns with less volatility than stocks, as well as gains in some bear markets.

We took a skeptical look at hedge-fund results, because the track record for the category is much shorter than that for stocks or bonds, and hedge funds offer much less transparency. Furthermore, hedge-fund performance databases are biased because funds can submit results—or not—for as long as they choose.

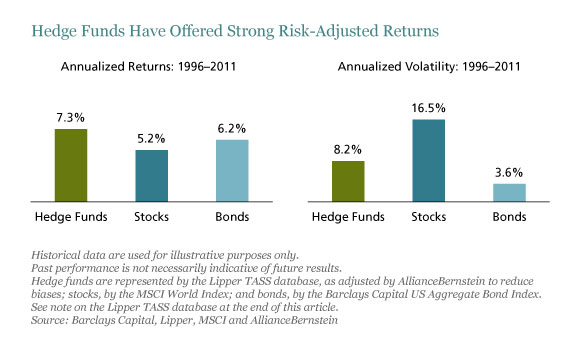

We arrived at an adjusted annual hedge-fund return of 7.3% from 1996 to 2011, the last full year for which data are available. (Hedge-fund returns were lower in 2012 but not enough to change meaningfully the results since 1996.) While 7.3% is well below the unadjusted return of 9.8%, it is still appealing compared with stocks and bonds, as the left side of the display below shows.

We also found that hedge funds were far less volatile than stocks over the 16-year period. The annualized volatility of the asset-weighted index of all hedge funds in the database was 8.2%, about half the 16.5% volatility of the MSCI World Index of global stocks, but above the 3.6% volatility of the Barclays Capital US Aggregate Bond Index, as the display also shows. Hedge funds seem to offer a more attractive trade-off between risk and return than traditional asset classes, even after adjusting for biases.

Lastly, we found that hedge funds diversified stocks effectively over this 16-year period, but not as well as bonds did: hedge funds’ correlation with stocks was about 0.6, while bonds’ correlation with stocks was about 0.2.

Most of the diversification benefit of hedge funds appears to come from the higher portion of their return that derives from alpha: 60%, versus 13% for a typical long-only manager. From 1996 to 2011, the median hedge-fund manager generated alpha of 3.3% per year, versus 0.4% for long-only stock managers, our research found.

With higher returns, lower volatility and good diversification benefits, hedge funds would seem to be a slam-dunk investment. But no one should make large investments based on 16 years of self-reported data. In future posts, I will explain how we rooted out biases in the data and discuss reasons for caution and our conclusions about prudent execution of a hedge-fund strategy.

The Lipper TASS database includes the net-of-fee performance of individual hedge funds whose managers have elected to report to the database. In constructing our hedge-fund and fund-of-funds indices, we included the performance of funds only after their managers decided to report to the database, and only for those funds that had at least $10 million in assets under management. We also included the performance of all funds in the database that are no longer currently reporting. Based on the above selection criteria, there were 4,766 distinct hedge funds in the database during the 1996–2011 period. The indices are asset-weighted.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AllianceBernstein portfolio-management teams.

Daniel B. Eagan is Head of the Wealth Management Group at Bernstein Wealth Management, a unit of AllianceBernstein.

Copyright © AllianceBernstein