Déjà Vu All Over Again

Tony Crescenzi, Andrew Bosomworth, Lupin Rahman, and Ben Emons, PIMCO

- If the eurozone is to endure, it will require reduced economic differences among countries and larger common fiscal capacity.

- Emerging market central banks are likely to remain in wait-and-see mode while looking to the U.S. for clarity on the fiscal negotiations and domestic macro prints for signs of moderation in both inflation and activity.

- While central banks in advanced economies have not traditionally used explicit policies to target exchange rates, the European debt crisis may change all that.

In this month’s Global Central Bank Focus, Tony Crescenzi suggests that Congressional cooperation is necessary to help the Federal Reserve heal the ailing U.S. economy, Andrew Bosomworth urges the EU to consider fiscal and political integration in order to survive, Lupin Rahman explores the prospects for continued growth in emerging markets and Ben Emons discusses the use of monetary policy to influence exchange rates.

The re-election of President Obama reinforces the likelihood that the bond market will remain anchored for quite some time to come by the extraordinary degree of monetary accommodation that the Federal Reserve is providing. This was likely to be true no matter who won the election, but President Obama’s re-election ensures that the Federal Reserve will remain chaired by an individual who will favor keeping in place a highly accommodative stance on monetary policy if Chairman Ben Bernanke leaves the Fed when his term expires in January 2014, as now appears likely. The printing press will keep rolling, in other words.

Monetary policy for the foreseeable future will be designed to smooth the deleveraging process by reflating deflated asset prices through an activist policy regime that utilizes three main tools:

- An exceptionally low policy rate.

- Asset purchases, primarily of longer-term agency mortgage-backed

and U.S. Treasury securities. - Communications strategies.

Using these tools, the Fed aims to accomplish three important goals:

- Flatten the forward curve, which is to say extend investors’ expectations of the timeline for when the Fed will increase its policy rate, the federal funds rate, which is today near zero percent.

- Suppress interest rate volatility. By promising to maintain a highly accommodative stance on monetary policy for a considerable time even after the economic recovery strengthens, the Fed’s bond buying should hold down interest rates, and a rate hike is unlikely. This suppresses the level of longer-term interest rates by reducing the so-called term premium that is embedded in bond yields, which is a fancy way of saying the amount of yield that bond investors demand for uncertainties regarding the Fed’s policy rate.

- Prod return-hungry investors to move outward along the risk spectrum.

In addition to this largely defensive approach, which is geared toward rehabilitating the much-damaged U.S. economy, the Fed will be playing offense by setting its policies to achieve a more rapid pace of economic growth than has been seen thus far during the economic recovery. The Fed began this new tack in September when it announced a third round of longer-term securities purchases, dubbed QE3, promising to purchase $40 billion of mortgage-backed securities every month until the outlook for the labor market improves substantially. The Fed hasn’t yet explicitly said what its growth target is, but it presumably is for nominal GDP to move closer to its historical growth rate of about 5% as opposed to its recent growth rate of about 4%. A growth rate of 5% would help the Fed achieve the objectives of its dual mandate on employment and inflation.

Searching for that can-do spirit

Of course, the Fed can’t accomplish this on its lonesome – money printing can’t possibly solve all that ails the U.S. economy; it can’t solve structural issues and it can’t make anything but paper currencies. All that the central bank can do is help foster financial conditions that facilitate the efficient use of capital.

If the U.S. is to rejuvenate its economy and improve its standard of living, federal lawmakers must do their part, too. The problem is, in Washington the “can-do” spirit has been turned upside down in recent years by the “do-nothing” Congress, which in its last session produced fewer than half the amount of laws produced during any other session of Congress dating back to 1947 (see Figure 1).

So, it is déjà vu all over again: The era of deleveraging is far from over, and the U.S. continues to face daunting challenges that can only be resolved through cooperation among the nation’s elected officials, whose rancorous existence behooves the Federal Reserve to do all it can to convince people to take a humongous leap of faith and continue to hope for a time when lawmakers will get their act together.

In largely maintaining the status quo, the American people have demonstrated enormous patience with Washington that politicians hopefully will graciously and dutifully embrace for the benefit of the nation. If not, the Fed will remain the only game in town. At some point, there will be nothing the Fed can do, so Washington had better get on the case before long.

ECB Focus: Can monetary union exist without fiscal union? – Andrew Bosomworth

Like many fundamental issues in life, the answer to this question is controversial. And it depends on the differences among countries sharing a common currency. Monetary union between two relatively homogenous countries, like the economic union practiced between Belgium and Luxembourg since 1922, is easier to master than a monetary union among a large group of heterogeneous states, like in the eurozone. The experience of the eurozone suggests its decentralized and rule-based fiscal system does not work. The onus is thus on the proponents of decentralized fiscal policy to prove that monetary union can work without fiscal union.

Today’s problems in the eurozone are twofold: they occur at the individual country level and at the level of the system itself. At the individual country level, some countries lost international competitiveness when their labor costs rose disproportionately to others in the union. Others developed bloated and inefficient public sectors, and the combination contributed to some losing market access. In losing market access, these countries also lost their fiscal sovereignty. At the system level, the eurozone is inadequately equipped to deal with asymmetric shocks within the union, like regional capital flight. Deprived of an exchange rate and lacking sufficient labour mobility, the eurozone’s governance structure has forced some current account deficit countries to the brink of insolvency. This is a type of market (or system) failure.

By providing liquidity, the ECB can buy fiscal policymakers some time to put their fiscal affairs in order. But this is all it can do. Monetary policy cannot restore solvency to an insolvent state. Fiscal agents must now grasp the opportunity to further deepen fiscal and political integration.

Together, the ECB’s policy initiatives and those adopted by governments – the awkwardly named two-pack, six-pack and fiscal compact – define the eurozone’s pre-federal stage. Ultimately, however, this will not suffice, in my opinion. The lessons from the history of monetary unions show that the pre-federal stage is unstable. While it can last a long time, as it did in the Scandinavian, Latin and Austro-Hungarian monetary unions, it can also end as these monetary unions did when individual member states embarked upon divergent fiscal paths.

The euro is an unfinished project. Ultimately, if it is to endure, it will require reduced economic differences among countries and larger common fiscal capacity. That will necessitate establishing a common fiscal agency, empowered to connect some federal taxation and expenditure policies directly with its citizens, and backed by a democratic legislative chamber. A euro solidarity surcharge and common defense services are areas where such fiscal capacity could begin. Nations are not built overnight. It is therefore important that the eurozone’s leaders elaborate upon the euro’s destination and roadmap. This will help anchor long-term investors’ expectations and should make the ECB’s job of buying time a lot less costly.

Emerging markets focus – Lupin Rahman

With the global backdrop fraught with uncertainty, EM central banks are in wait-and-see mode. Most will likely leave policy rates low while reserving the option of further easing if the global growth backdrop deteriorates. With policy rates in developed markets firmly anchored at the zero-bound and growth in 2012 disappointing, most EM central banks with space to cut rates did so – with some reaching historical lows. Their major constraint, which prevented them from easing more aggressively, was concerns about possible second-round effects from the food price shock earlier in the year.

Looking ahead, EM central banks are likely to have a significantly diminished bias for a hawkish stance. Headline inflation is showing signs of moderating as the impact of the food price shock abates and base effects turn favorable. At the same time, global growth risks remain a concern given U.S. fiscal cliff threats, a muted stabilization in China and debt deleveraging in the eurozone peripherals.

EM currency dynamics also are supportive of this more dovish stance. Global quantitative easing policies by developed market central banks have underpinned expectations of weakness in major currencies, particularly the U.S. dollar given Bernanke’s strong signal on QE vis-à-vis the ECB, Bank of England or Bank of Japan. The lower base of EM currencies, following the selloff in the second half of 2011, offers EM policymakers the scope for using foreign exchange appreciation as a tool for managing monetary conditions before concerns about competitiveness become a constraint. Alongside this, if we see the economic cycle in EM stabilizing and headline risks from major global events, including the U.S. elections and Greek bailout, moderate, EM currencies should appreciate.

Another element entering central bank reaction functions is the increasing interest by global investors in EM local markets. Inflows into EM local currency funds have been robust in 2012, supporting EM local yields and, in some cases, allowing deepening and extension of the curve. The drivers of these flows have been mainly structural, with reports of reserve managers and real money managers dominating flows. This structural element is further underpinned by the inclusion of EM local markets into global bond indexes such as South Africa’s entrance into Citigroup’s World Government Bond Index this year, which many global investors (not only dedicated EM managers) are benchmarked against.

Taking these together, EM central banks are likely to remain in wait-and-see mode while looking to the U.S. for clarity on the fiscal negotiations and domestic macro prints for signs of moderation in both inflation and activity.

Exchange rate promises – Ben Emons

While central banks in advanced economies have not traditionally used explicit policies to target exchange rates, the European debt crisis may change all that. As the crisis progressed, countries including Australia, Sweden, Switzerland, Norway, Japan and New Zealand experienced excessive currency strength. This posed a problem for their respective monetary authorities’ price stability mandates and inflation targets. If the currency strengthened too much, inflation could fall short of its target. If they eased too quickly to stem currency appreciation, inflation could overshoot its target. The extent of this potential for undershooting and overshooting varies by country.

Therefore, exchange rates have become a primary focus as advanced economies use “implicit currency targeting” to optimize their inflation targeting measures. This implies that exchange rates are being used as an extension tool to influence financial conditions and economic growth. This could have several implications.

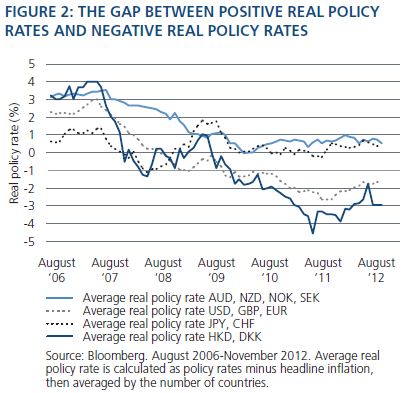

For one, by pegging one currency to another, the monetary policy of one country is linked to the monetary policy of another. The central banks of Hong Kong and Denmark are examples of such explicit currency pegging, and as a result their real rates are negative due to the policies, respectively, of the Fed and the ECB. In economies with central banks that still have real policy rates (like Australia, Sweden, Norway, Japan and New Zealand), the pace of currency appreciation has been relative to the trajectory of inflation vs. their respective targets. The threat of potential undershooting should increase as exchange rate appreciation momentum accelerates. This will likely result in more rate cuts in Australia, New Zealand, Norway and Sweden in order to attempt to stabilize their currencies. As a result, positive real policy rates could turn negative. That would have implications for capital flows to and from these countries and influence currency valuation.

As shown in Figure 2, there is a gap between the positive real interest rates of countries with strong currencies and the negative real rates of countries that have pegged or artificially lower currencies as a result of policy activism. A slow convergence may occur, as countries with positive real rates actively look to lower rates to depreciate their overvalued currencies.

In principle, all central banks see a weaker currency as a convenient way of achieving objectives, especially when other tools are limited. Exchange rate targeting is another form of reflation when central banks actively pursue a weaker currency. Responding to one another’s policy actions with “soft” currency pegging creates, to a degree, a semi-fixed exchange rate mechanism. Within such a system, central banks that strive to achieve stable inflation via reflation led by a weaker currency may experience real effective exchange variability. Following the route of soft currency pegs, competitiveness across all major developed economies could be affected. This frustrates all attempts to boost growth and, with fiscal policy being constrained, central banks have to revert to more creative and aggressive easing actions. As that process accelerates, currency valuations play a greater role in policy timing, especially in carrying further the theme of reflation.

Past performance is not a guarantee or a reliable indicator of future results. All investments contain risk and may lose value. This material contains the current opinions of the authors but not necessarily those of PIMCO and such opinions are subject to change without notice. This material is distributed for informational purposes only. Forecasts, estimates, and certain information contained herein are based upon proprietary research and should not be considered as investment advice or a recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product. Information contained herein has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but not guaranteed. No part of this material may be reproduced in any form, or referred to in any other publication, without express written permission. PIMCO and YOUR GLOBAL INVESTMENT AUTHORITY are trademarks or registered trademarks of Allianz Asset Management of America L.P. and Pacific Investment Management Company LLC, respectively, in the United States and throughout the world.

Copyright © 2012, PIMCO