by Axel Merk & Kieran Osborne, CFA, Merk Funds

September 26, 2012

Central bankers around the world may be providing a backstop to the financial markets in much the same way Greenspan did during the “Goldilocks” years, but when the short-term euphoria wears off, will the negative repercussions be even more severe? Bernanke’s Federal Reserve (Fed) appears to specifically target equity market appreciation as part of its offensive in bringing down the unemployment rate; expectations are high: every time the market sells off, the Fed might simply print more money. We fear central bankers have overstepped their reach, and the implications of their actions may be much worse than the anticipated benefits.

To an extent, the effects of today’s monetary policies resemble the “Greenspan Put” (named after former Fed Chair Alan Greenspan) in the years leading up to the crisis. Today’s central bankers have been quite straight forward in communicating their stance: they appear willing to step in with evermore liquidity should the global economy show any signs of further weakness. Bernanke’s Fed has gone even further: the Fed has stated it’s accommodative policies will “remain appropriate for a considerable time after the economic recovery strengthens”. In other words, financial markets will be awash with liquidity for an extended period, even if we see signs of a sustainable economic recovery.

At first glance, this may appear a positive development for investors holding stocks and other risky assets. After all, Bernanke appears willing to underwrite your investments over the foreseeable future. Indeed, Bernanke appears to specifically target equity market appreciation, on many occasions noting one of the key benefits of quantitative easing (QE) has been to increase stock prices. Notably, while he believes the Fed’s QE policies have had a positive impact on stock prices, he considers it has not caused increases to inflation expectations or commodity prices. We disagree, which we elaborate below. Ultimately, the Fed may have reached too far, bringing risks to economic stability and elevated levels of volatility; the full implications of its actions may be somewhat dire down the road.

From the Bank of Japan and the People’s Bank of China to the European Central Bank (ECB), the Bank of England (BoE) and the Fed, central bankers are either putting their money where their mouth is (quite literally) or strongly insinuating that continued, ongoing easing policies are needed to prevent another significant downturn in global economic activity. While all the excess printed money may or may not have the desired effect of stimulating the global economy, the money does find its way somewhere; unfortunately, most central bankers appear to fail to realize that they simply cannot control where that money ends up.

Fed Chair Bernanke’s Achilles’ heel since the onset of the financial crisis has been the housing sector. It’s no surprise why the Fed bought over a trillion dollars worth of mortgage backed securities (MBS) since 2009: to re-inflate home prices and in so doing, bail out all those underwater with their mortgages. The problem was, it didn’t work – house prices continued to weaken across the nation, and have stagnated to this day. Now, the Fed has announced another MBS purchase program, this time open-ended, under the auspices of “QE3”. Do they believe the time is now ripe for MBS purchases to positively impact the housing market and thus the economy? Unfortunately, the first MBS purchase program failed to have its desired effect; we do not foresee how QE3 will be any better at stimulating house price appreciation.

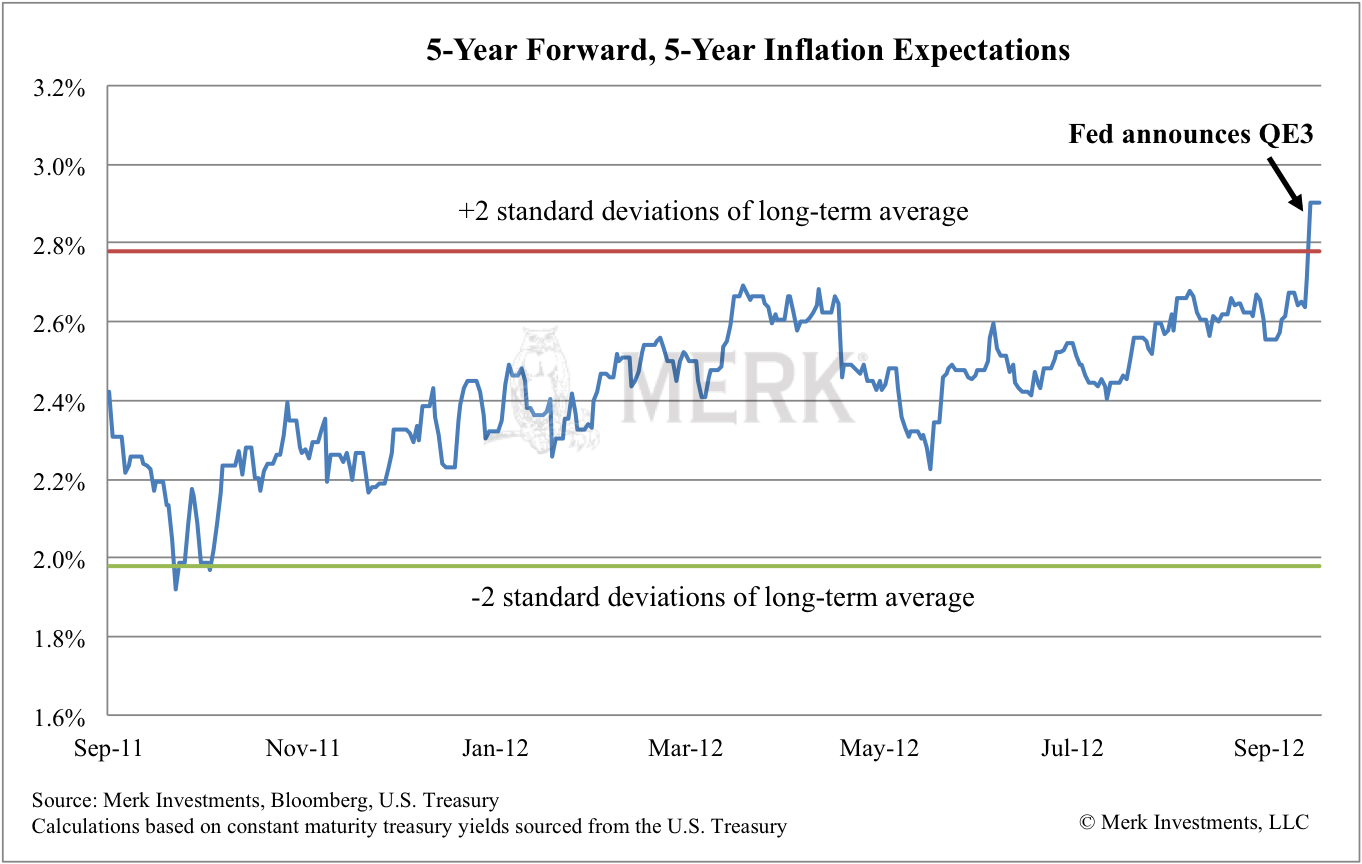

One of the things we believe such actions do stimulate are inflation expectations. Indeed, the jump in market-implied future inflationary expectations in reaction to the Fed’s QE3 decision was quite remarkable:

In contrast to Bernanke’s views that QE does not cause commodity price appreciation, in our assessment, much of the freshly printed money only serves to inflate the value of assets that exhibit the greatest level of monetary sensitivity: commodities and natural resources. These are essential in the manufacture and production of goods and services purchased by U.S. consumers on a daily basis. As such, inflated commodity and resources prices ultimately pressure consumer price inflation, as the consumer’s “everyday basket of goods” becomes evermore expensive. The ongoing weakness in the U.S. dollar only serves to compound these inflationary pressures. A weak dollar, we believe, is part of Bernanke’s strategy to stimulate the U.S. economy through stimulating exports. While we fundamentally disagree that this is sound monetary policy for the U.S. to pursue, the inflationary ramifications are clear: the U.S. imports a great deal from abroad; every time the dollar depreciates against a currency of a country from which the U.S. imports, the price of those imports rises.

Not only have the Fed’s actions heightened inflationary risks, but we also believe it implicitly heightens the risk that the Fed gets monetary policy wrong. For instance, Fed Chair Bernanke believes that the Fed’s non-standard policies since 2008 may have helped lower 10-year Treasury yields by over 1.5%1. In so doing, the Fed has taken away a key metric used to gauge the economy and thus set appropriate monetary policy: free market interest rates. The Fed has historically relied on long-term yields, such as the 10-year and 30-year Treasury yield, as part of its assessment of the overall health of the economy. In manipulating those same yields, the Fed can no longer rely upon them to provide valuable information on the health and trajectory of the economy. In other words, the more the Fed meddles in the market through non-standard measures, the more the Fed is in the dark regarding the appropriateness of monetary policy. Such a situation inherently creates an additional level of uncertainty over the U.S. economy, U.S. monetary policy, and may continue to underpin weakness in the U.S. dollar.

The vast amounts of liquidity provided via the Fed’s quantitative easing programs will, at some point, have to be reined in. Whether due to inflationary pressures or a sustainable recovery, only time will tell, but the need to rein in liquidity may create massive headaches down the road. Given the ongoing high level of leverage employed in the economy, such monetary tightening runs the risk of undermining any economic recovery and potentially causing it to crash back down, as the likelihood of it negatively affecting consumer spending is high. With a still-leveraged consumer, rising rates may be overly painful, dramatically slowing consumer spending and, in turn, the economy. Such dynamics may have an outsized impact on the U.S. economy, given consumer spending makes up approximately 70% of U.S. GDP.

All of which underpins our view that there is a significant risk that the Fed has gotten monetary policy wrong. We consider the Fed’s actions have not only heightened inflationary risks, but have also inherently created risks to appropriate monetary policy going forward. Both of which will likely contribute to ongoing high levels of market volatility over the foreseeable future.

With so many dynamics yet to be played out globally, and with central bankers becoming evermore active in meddling with economic dynamics around the world, investors may want to consider preparing for the potential ramifications of such policies. While we may disagree with the policies being pursued, central bankers appear to be at least predictable in their decisions. We believe the currency market provides the most effective way to position oneself to protect and profit from the implications of such monetary policies.

In the current environment, the general equity market seems to be moving on the back of the next anticipated move of policy makers, and less so on fundamentals, but company-specific risks remain. With the outlook for the economy still on tenterhooks, many companies have been missing earnings forecasts. Currencies don’t have this additional layer of risk. As a result, currencies may be the “cleanest” way of positioning oneself for the next policy move. Historically, currencies have also exhibited much lower levels of volatility relative to equities, when no leverage is employed. As such, investors may want to consider adding a professionally managed basket of currencies to their existing portfolios.

Please sign up to our newsletter to be informed as we discuss global dynamics and their impact on gold and currencies. Engage with me directly at Twitter.com/AxelMerk to comment on Merk Insights and to receive provide real-time updates on the economy, currencies, and global dynamics.

Axel Merk & Kieran Osborne, CFA

Axel Merk is President and Chief Investment Officer, Merk Investments

Merk Investments, Manager of the Merk Funds.

Kieran Osborne is Senior Analyst at Merk.

Copyright © Merk Funds