Tomatoes and the Low Vol Effect

by Ryan Larson, Research Affiliates

Growing up, my sister and I spent summers at our grandparents’ house where one of our favorite treats was fresh sliced tomatoes with sugar on top. Snack time always brought out the fun debate about whether tomatoes are a fruit or vegetable. Without the Internet to render a definitive verdict, we settled on enjoy- ing the tomato regardless of its categorization.

Today we can find out quickly whether toma- toes are a vegetable or fruit. The answer is both! Botanically, tomatoes are a fruit. Cultur- ally and legally, they are a vegetable. In 1894, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that tomatoes were a vegetable, allowing the U.S. Govern- ment to impose a tariff on imported tomatoes, protecting domestic farmers.1

Like tomatoes to farmers and botanists, inves- tors classify risk in equity portfolios differently depending on their point of reference. In its simplest form, there are two types of equity risk: absolute risk and relative risk. Research shows that in an ideal world, investors should prefer to invest 100% in low volatility strate- gies that minimize absolute risk. However, the overwhelming trend to delegate authority to institutional money managers—who generally focus on relative performance—makes this outcome unrealistic. This issue of Fundamentals explores ways to improve the outcome for both absolute and relative risk investors.

Absolute to Relative Risk

For the first three-quarters of the 20th century, the majority of outstanding equity shares were held by individual investors who focused on total return and absolute risk.2 Individuals tended to purchase blue-chip stocks in a buy-and-hold strategy, banking the dividends on a regular basis. There were few specialized institutional money managers acting on behalf of other investors.3

Investment success was measured by a stock’s total return (dividends paid plus stock price gain) relative to its absolute risk (standard deviation). William Sharpe (1966) formalized the concept of return relative to absolute risk when he introduced the “reward-to-variability ratio”; the formula was later renamed the “Sharpe ratio.” Two changes in the 1970s and 1980s contributed to a shift from absolute risk to relative risk as the frame of reference. The first was the growth of assets in pension funds that led to financial intermediation, and the second was the emergence of passive capitalization-weighted indexing.

Assets invested in plans that outsource investment management (the most notable being public and corporate defined benefit plans and 401(k) plans) exploded from $369 billion in 1974 to $19 trillion today.4 This dele- gation of investment authority to institutional money managers meant a need to measure the success of these hired guns. The anchor for performance success became the market portfolio—the S&P 500 Index, or broader indices, such as the Russell 3000 Index. Conveniently, in 1973, cap- weighted index funds were developed to offer investors an easy, cheap way to access stocks, emphasizing relative risk investing even more.

Today, the clear majority of equity strate- gies operate either explicitly or implicitly with an eye toward minimizing relative risk. Indeed, the standard deviation and beta of most managers is very similar.5 Thus, the differentiating factors in man- ager selection should be excess return, tracking error, and the ratio between the two—the information ratio. If a manager experiences a lot of tracking error and seri- ously underperforms the index, the man- ager faces the risk of termination. With the average manager running a tracking error of over 6%, randomness alone puts him at risk of getting fired.6 Three years is typically the longest boards allow a man- ager to underperform the market before pulling the plug. Portfolio managers are a self-preservation-oriented bunch, so they began to manage their portfolios with an eye on the index and toward minimiz- ing relative risk (tracking error), with less concern for absolute risk (standard deviation).

With the advent of the Fundamental Index® approach in early 2005, investors suddenly had a second implementation option for a relative risk pursuit that sought alpha from a different angle. The Fundamental Index method eliminates “negative alpha”; that is, the inefficiency caused by a cap-weighted index portfolio overweighting overvalued stocks and underweighting undervalued stocks and not rebalancing.

Back to the Future?

Today we are witnessing a renaissance of sorts as investors, battered by the bear markets of the 2000s, are more open to the idea of equity strategies focused on minimizing absolute risk. In fact, the strong shift into hedge funds during the past decade reflects a desire to reduce absolute risk. However, we believe there is a superior way to achieve this goal: low volatility strategies, which offer nearly the same statistical properties of hedge funds, but do so in a liquid, transparent, low cost manner—and with better Sharpe ratios.7

Low volatility strategies contradict what finance students learned in business school that the security market line (SML) slopes upward linearly. In other words, theory says that higher volatility or higher beta stocks should produce higher rates of return to compensate for the greater market risk. Evidence exists since the 1970s that the SML is much flatter than CAPM predicts.8 Perversely, low volatility stocks earn higher returns than high volatility stocks!

Most managers who have launched low volatility strategies over the past five to seven years to capitalize on “de-risking demand” build their portfolios through a quantitative optimization process that estimates the covariance matrix in a complicated, black-box solution. We observe these optimized low volatility strategies tend to emphasize small-cap stocks and have high turnover (90%). However, our research finds that there is no ex ante long-term performance differ- ence between any of these low volatility methodologies! All “true” low volatility portfolios should earn a premium return of about 2% in the United States and do so with 25% less absolute risk than the benchmark.9 Even something as simple as screening out high volatility stocks and weighting by the inverse of volatility (i.e., allocating more to low volatility stocks) will produce a comparable result. (Our low volatility approach employs a similar investor-friendly process.)

The explanations for the seemingly counterintuitive result of the low volatil- ity anomaly are nearly as widespread as the amount of products entering the marketplace. Our view is far simpler. First, the excess return of the strategies comes from the fact that, like the Fundamental Index method or even equal-weighting, low volatility methodologies don’t use price to weight the portfolio. Therefore, before transaction costs, they should produce a similar excess return to any other non-price-weighted strategy. And indeed they do. The risk reduction is a simple byproduct of focusing on the lower volatility portion of the equity market. Therefore, what investors need to focus on is finding the low volatility strategy that is simple and intuitive with the lowest cost and easiest implementation.

Low volatility strategies can lead to a high amount of investor regret because of their very large tracking error of 8–10%, leading to a high probability of buying and sell-ing those strategies at the wrong time because of relative risk benchmarking. For example, during 2011 low volatility stocks outperformed the broad stock market by 10%, then lagged by 5% in first quarter 2012, and outperformed again in the second quarter 2012 by 5%.10 What a seesaw! Because of high tracking error, successful low volatility investing must throw out any comparison to relative risk measures such as the information ratio and re-frame performance relative to a different anchor: the Sharpe ratio.

Choose Your Risk Wisely

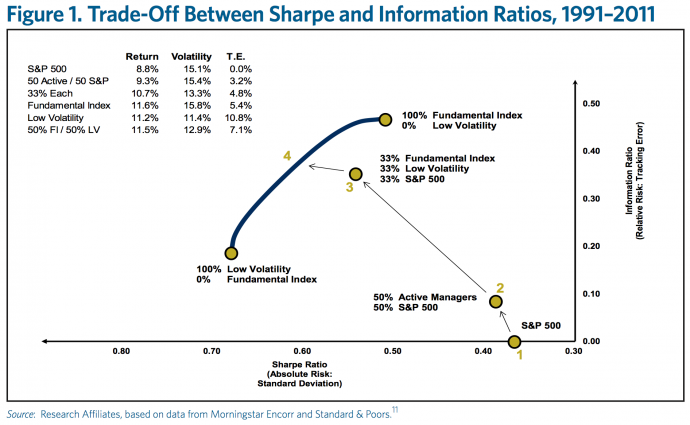

Investors now have two very distinct paths for gaining equity exposure. Figure 1 outlines the trade-offs between the two risk focuses. The vertical axis measures the information ratio, or the excess return per unit of tracking error. The relative risk investor, concerned with tracking error, seeks to maximize the information ratio often at the expense of higher absolute volatility. The horizontal axis displays the Sharpe ratio, or the excess return of the portfolio over cash relative to the port- folio standard deviation. The absolute risk investor, by focusing on reducing standard deviation, defines success by the Sharpe ratio, but incurs sizable tracking error (relative risk) in doing so. To illustrate the trade-offs, we plot four reference portfolios:

- S&P 500—This benchmark portfolio has an information ratio of 0 as it has no excess return or tracking error against itself and a Sharpe ratio of less than 0.4. The market portfolio is an inefficient long-term portfolio solution.

- Active Managers—This portfolio rep- resents the typical way relative risk investors have sought to increase the information ratio; over the 1991–2011 time period, the average manager earns a slight premium over the market.

- Fundamental Index Method—This portfolio illustrates the improved information ratio (at a reasonable tracking error level) achievable by applying a non-price methodology in an economically representative manner. Because the Fundamental Index method owns a very similar roster of companies to capitaliza- tion weighting, it tends to have a similar volatility level and so the Sharpe ratio improves only margin- ally. Thus, the Fundamental Index method is an ideal solution for those that live predominantly in the rela- tive risk camp.

- Low Volatility—This portfolio illus- trates the improved Sharpe ratio achievable by shifting from relative risk to absolute risk-focused equity investing. Low volatility strategies earn a near one-to-one ratio of return to risk, while cap-weighted S&P 500 investors take on double the amount of risk to earn the same return!

It should be readily apparent that it is very difficult for a single portfolio approach to be both a relative risk and an absolute risk winner. The more one wants to shift from a relative approach to an absolute one, the more one will have to screen out large portions of the market and, accord- ingly, accept more tracking error. On the flipside, a shift from absolute risk to relative risk will mean purchasing higher beta stocks that comprise a large portion of the market. Predictably, this increases absolute volatility. Only the lucky tomato gets to be both a fruit and a vegetable.

We assert that a critical takeaway from Figure 1 is that the first step of an equity structure review ought to be a discussion of the client’s primary risk measure. A client with substantial oversight and reg- ular peer group comparisons is likely to prefer a continued reliance upon relative risk and information ratio maximization. Investors willing to take more “maverick” risk12 can make a conscious choice to devote all, or some portion, of their equity portfolio to Sharpe ratio maximization that presumably enjoys a closer link with their liabilities.

Clients who are willing to take some tracking error risk, but are not willing to go all in, can split their allocation among the various portfolios. A simple strategy of equally weighting allocations to the traditional cap-weighted index, the Fun- damental Index method and low volatility increases returns by 2% and decreases risk 2% relative to the conventional portfolio! This equity portfolio earns 11% returns with 13% risk, all with manage- able tracking error under 5%.13 Of course, these results are achieved with no stock picking, no manager due diligence, and no forecasting. Further, a thoughtfully designed Fundamental Index portfolio and low volatility approach can capture nearly all of these “paper portfolio” results by emphasizing low turnover, sizable capacity, and economic representation.

Conclusion

Fruit or vegetable, a tomato with sugar on it tastes great. But the difference between relative risk and absolute risk is more than just semantics—it relates to investor preferences. For the investor more concerned about tracking error and measurement against a benchmark and his peers, a relative risk approach is more relevant. For the investor who desires avoiding sharp downdrafts but does not mind tracking error deviation, an absolute risk approach based on improved Sharpe ratios may be more appropriate. In either case, both relative and absolute risk investors can improve the structure of their equity portfolios by migrating away from the conventional equity allocation.

Footnotes:

1. Nix v. Hedden. Vegetables were subject to the Tariff Act of 1883, while fruits were exempt. The U.S. Commerce Department still clas- sifies tomatoes as vegetables, although the tariff was removed in 1994 with the passage of NAFTA.

2. In 1968, institutional investors owned just 15% of U.S. stock market shares. Today, that figure is approximately 75%. See Baker, Bradley and Wurgler (2011).

3. Most “institutional” investors were bank trust departments invest- ing on behalf of wealthy families. Hedge funds didn’t exist, with the exception of a couple of pioneers like the Graham–Newman partner- ship and Alfred Winslow Jones.

4. According to the Employee Benefit Research Institute, there was $162 billion in U.S. state and local retirement pension plans in 1979 and $2.7 trillion in 2010, and $64 billion in federal government retirement plans in 1979 and $1.3 trillion in 2009. According to the Investment Company Institute, there is $3.4 trillion invested in 401(k) plans in 1Q2012, up from zero in 1980, and $2.5 trillion in corporate pension plans in 1Q2012, up from $130 billion in 1974. The balance is in other DC plans, IRAs, and annuities.

5. As an example of how active managers are not that different from the market, the eVestment Alliance U.S. Large Cap manager universe (758 managers) over the past 10 years (6/2002–6/2012) reveals an average beta of 0.99 with the bulk of managers’ betas between 0.93 and 1.04. The results are nearly identical for the past 20 years (6/1992–6/2012), but with a smaller subset of 194 managers. The majority of managers have standard deviations between 15–17% for both of these time periods, right around the market’s 15.5%.

6. There is a one-in-three chance during a “normal” one-standard deviation event any given year a manager would underperform by 6%. Suppose the manager underperforms by 6% in the first year and earns no excess returns the next two years. This would mean finishing the all-important three-year judgment period with about a –2% relative underperformance before fees. Quite often, that type of underperformance results in termination for active managers.

7. Over the past 10 years, the HFRI Equity Hedge Index returned 4.5% annualized with 9% volatility, while low volatility stocks earned 7% with 11% volatility. The Sharpe ratio of low volatility is better than hedge funds! Correlation to the S&P 500 Index was 0.85 for both hedge funds and low volatility, and tracking error to the S&P was approximately 10% for both. To us, investors are much better off using low volatility equities to maximize Sharpe ratio than high cost hedge funds.

8. See Fischer Black (1972) and Robert Haugen (1972 and 1975). 9. Kuo and Li (2012).

10. Comparing the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index to the S&P 500 Index.

11. We use the S&P 500 Low Volatility Index to represent the returns of low volatility portfolios. The S&P 500 Low Volatility Index builds a portfolio of the 100 stocks within the broad S&P 500 that had the lowest standard deviation of returns over the past 252 trading days. It is rebalanced quarterly. Its inception was January 1, 1991, so we use that as a beginning point for the study. Also, going back in time earlier than 1991 becomes difficult to find a broad set of active managers that are truly representative of an investor’s opportunity set. Starting in 1991 there are just 162 managers in the eVestment Large Cap Equity universe for the study period. This dataset suffers from survivorship bias, and is gross of fees. Thus, we are giving active management an edge here, as their positive 1% excess return over this time period has been shown by many researchers to be well above what an actual investor earns through active management,

which is typically negative alpha after costs.

12. Maverick risk describes the willingness to adopt an asset allocation

that looks very different from that of the typical plan. Most U.S. pen- sion portfolios are aligned around a 60% equity / 40% bond anchor with some allocation to alternatives. Within the equity structure, the conventional portfolios are heavy in domestic equities, and active management and cap-weighted indexing.

13. Of course, a 50/50 split between the Fundamental Index and low volatility strategies would deliver a more optimal portfolio!

References

Baker, Malcolm, Brendan Bradley, and Jeffrey Wurgler. 2011. “Benchmarks as Limits to Arbitrage: Understanding the Low-Volatility Anomaly.” Finan- cial Analysts Journal, vol. 67, no. 1 (January/February):40–54.

Black, Fischer. 1972. “Capital Market Equilibrium with Restricted Borrow- ing.” Journal of Business, vol. 4, no. 3 (July):444–455.

Black, Fischer, Michael C. Jensen, and Myron Scholes. 1972. “The Capital Asset Pricing Model: Some Empirical Tests.” In Studies in the Theory of Capital Markets. Edited by Michael C. Jensen. New York: Praeger.

Haugen, Robert A., and A. James Heins. 1972. “On the Evidence Support- ing the Existence of Risk Premiums in the Capital Markets.” Wisconsin Working Paper (December).

_______. 1975. “Risk and the Rate of Return on Financial Assets: Some Old Wine in New Bottles.” Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, vol. 10, no. 5 (December):775–784.

Kuo, Li-Lan and Feifei Li. 2012. “An Investor’s Low Volatility Strategy.” Research Affiliates White Paper (June).

Sharpe, William F. 1966. “Mutual Fund Performance.” Journal of Business, vol. 39, no. 1 (January):119–138.

_______. 1994. “The Sharpe Ratio.” Journal of Portfolio Management, vol. 21, no. 1 (Fall):49–58.