by Axel Merk, Merk Funds

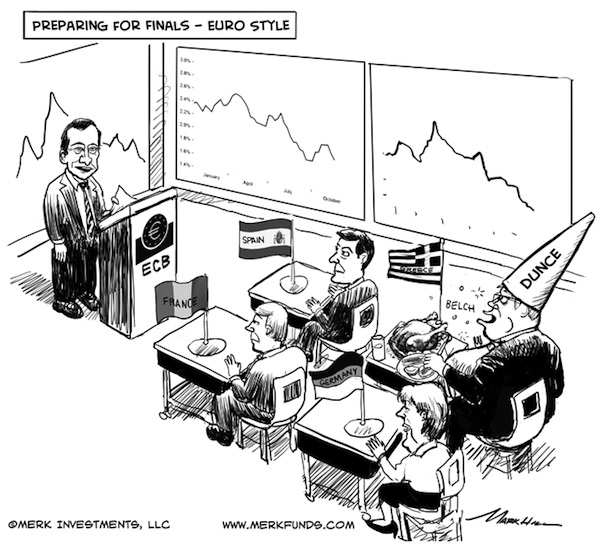

The management of the Eurozone debt crisis is dysfunctional. In our assessment, to save the Euro, policy makers must focus on competitiveness, common sense and communication. If policy makers strived to achieve just one of these principles, the Euro might outshine the U.S. dollar.

Communication

Let’s start with the simplest of them all: communication. In a crisis, great leaders have a no-nonsense approach to communication: providing unembellished facts, a vision, a path on how to get there, as well as progress reports. Just as in any crisis, such a leader typically only has limited influence on the events playing out, but serves as a catalyst to rally the troops, provide optimism, avoid panics, explain sacrifices that must be taken, and show people the light at the end of the tunnel. The Eurozone needs a communicator. It can even be more than one.

The one unifying face of the Eurozone is Mario Draghi, head of the European Central Bank (ECB). Better than his predecessor, Draghi is able to articulate the issues and has been lecturing political leaders on their job when it comes to, among other things, fiscal sustainability and structural reform. Draghi has made it clear that while liquidity is abundant in the Eurozone, it is rather “fragmented”; as such monetary policy is not the bottleneck, instead, governments and regulators must live up to their duties. However, Draghi is the first to point out that he cannot be the spokesperson for fiscal and regulatory matters.

Starting at the top, the executive branch of the European Union is the European Commission, headed by José Manuel Barroso. Interested in the vision Europe so desperately needs? Barroso’s vision should give the answers; unfortunately, it comes across like a school essay, unlikely to go down in history as the vision that saved the European project. Google is proof that his office must do better in communicating with the public: the Commission’s website ranks third in results when explicitly searching for it.

Olli Rehn, EU commissioner on monetary affairs, is the public face for the political side of the euro. While Rehn has achieved much given the limited authority he has been given, we urge him to take a bigger public profile. In announcing the Spanish bank bailout, his office released a statement saying “that the Commission is ready to proceed in close liaison with the ECB, EBA and the IMF, and to propose appropriate conditionality for the financial sector.” The statement goes on to read “The Commission is ready to proceed swiftly with the necessary assessment…” – an action plan would have been preferred.

The EBA referenced above is the European Banking Authority, established only in 2011. The head of the EBA is Andrea Enria. Who? If the Eurozone wants to move towards a “banking union”, Enria needs to work harder in becoming a household name. As of this writing, the latest headline on the EBA’s website appears ill suited for public consumption: “Consultation paper on draft implementing technical standards on supervisory reporting requirements for liquidity coverage and stable funding”. Amongst important topics that have not been addressed in the Spanish banking bailout is what authority the European Banking Authority (EBA) will have in restructuring Spanish banks. Cronyism has left its regional lenders, the cajas, uncompetitive. Finland’s Prime Minister Katainen lamented after the announcement of the Spanish bank rescue, “there must be a possibility to restructure the banking sector because it doesn't make sense to recapitalize banks which are not capable of running” – the concern is fair and should have been pre-emptively addressed by the EBA. Instead, in typical Eurozone fashion, the meddling is eroding trust. For goodness sake, this is supposed to be a €100 billion bank bailout, not a textbook approach on how to squander yet another opportunity to tame the debt crisis.

Instead, in explaining the Spanish banking bailout, conservative Spanish Prime Minister Rajoy bragged to his domestic audience about how Spain avoided a bailout (really?). Some polls suggest 80% of Spaniards have “little or no” confidence in him – that’s half a year after his party won an absolute majority (if it’s any consolation, the public trusts his Socialist opponent even less). In our assessment, based on the attributes outlined of what the communication skills of a great leader may be, Rajoy flunks on all accounts. Rajoy appears more interested in playing games of chicken with Eurzone leaders than in real reform. But we are getting ahead of ourselves.

Competitiveness

Communication can only do so much. No bank bailout for Spain will get its economy back on its feet if Spain is not an attractive place to invest in. No bailout will cure Greece, unless capital wants to come to Greece. Differently said, austerity is the easy part; structural reform is the tough job. The key “encouragement” to engage in structural reform has come from the bond market: the higher the cost of borrowing for governments, the greater the incentive to get one’s house in order. Unfortunately, a side effect of the bailouts is that such incentive may be lost. Spanish Prime Minister Rajoy is proof of that: whenever the pressure of the bond market increases, reforms are promised; the moment the pressure abates, these promises are watered down.

While Rajoy encompasses just about all that’s wrong with the Eurozone process, it’s the (lack of) process rather than the person that is so detrimental. In Spain’s example, painful austerity measures have been implemented. Now, Rajoy argues, it’s time for European leaders to step up to the plate and do their part. But last time we checked, deficits continued to pile up. Rajoy has argued that measures that are too draconian now are unwise. Unfortunately, it takes years to build up confidence, but it can be destroyed in relatively short order; once destroyed, an enormous effort must be undertaken if confidence is to be regained. Half-baked solutions won’t appease the market. To reduce a youth unemployment rate of over 50%, make it easier for companies to be formed and conduct their business, easier to hire and fire people. Pumping money into a non-competitive banking system won’t lead to a sustainable recovery.

The “fiscal compact” policy makers are calling for is happening by default, as an increasing number of countries give up sovereign control over their budgeting in return for funding from the IMF and Eurozone. Similarly, the path towards a “banking union” appears to be shaping up through bank bailouts, as countries asking for help will have to yield control over their banking system.

And while we have been bashing Spain, Germany is about to destroy the competitiveness of its banking system. In order to win the required 2/3rds majority in parliament to pass the “fiscal compact”, the German government needs approval from the opposition. To get such approval, the Merkel government is proceeding with the introduction of a financial transaction tax. London, New York and Singapore ought to write thank you letters. It might be more prudent to let peripheral banks fail than to potentially jeopardize the long-term competitiveness of the Eurozone banking sector.

Common sense

Unfortunately, with more centralized management through bailout regimes, the focus shifts from improving the local economy towards managing the bailout régime, trying to maximize the money that can be extracted from the rescue funds. Instead, common sense solutions should be a top priority. Since the Spanish banking bailout is the most recent example, let’s ponder a few questions:

Why would you keep your money in a Spanish bank? In the U.S., some people put their money into community or other local banks, but many put their deposits with large, national banks. Similarly, why would you put your money into one of the Spanish cajas, even if well capitalized, when you can open up an account with Deutsche Bank? Could it be that the Spanish banking sector is too large? Could it be that, rather than propping up failed institutions, the government should focus on attracting capital from any institution that wants to come to Spain? Could it be that the focus should be on making Spain an attractive place to invest in?

Why do we have national bank regulators rather than a pan-European regulator? Well, in 2011, the European Banking Authority (EBA) was created. Yet, it’s the national bank regulators that dictate how domestic banks are run. And guess what, national bank regulators declare domestic debt to be risk free, and as such, banks would typically not put capital aside against their own national debt. Banks are in the business of managing risk, but if they are told to classify something as risk-free that is clearly risky, they may be wise not to touch their own sovereign debt with a broomstick. Germany, the poster child in this crisis, is one of the countries that has historically been reluctant to yield power to Brussels (although they are portrayed as more pragmatic these days). We would shed no tears to see the German bank regulator BAFIN yield authority to the EBA. Remember when banks published their sovereign debt holdings last year at instructions of the EBA? Well, BAFIN wanted to give German banks a free pass. Fortunately, market forces prevailed (by selling German bank stocks and debt) and encouraged the voluntary publication of the data.

And why does the ECB not take a lead in creating a ‘banking union’ by converting national central banks to divisions of the ECB? Currently, when money flows from Spain to Germany, the Bank of Spain incurs a liability at the ECB; in return, the Bundesbank has a claim against the ECB. In a true currency union, such flows should not matter. Instead, a formerly cryptic measure, TARGET2, that measures such flows, is closely followed as an indicator of capital flight from the periphery. To eliminate the concern that a country’s exit from the Eurozone could poke a major hole in the ECB’s balance sheet, the ECB should merge the national central banks, turning them into ECB divisions.

Empower the people, not the bureaucrats. Policy makers must find a way for local governments to own their own problems. When things fail, local governments must be held accountable. It cannot be that the Dutch, Finns and Germans are blamed for the Greeks failing to meet their goals. Some claim this may only be achieved when countries have independent currencies. However, there might be a better way: ECB President Draghi has urged policy makers to clearly define roles, deadlines and conditions to be satisfied. Crises will happen periodically, but they are far less stressful if sound institutional processes are in place. The ire when things go wrong can then be directed at the party responsible. This is not rocket science, but sounds like common sense to us.

In our assessment, the euro has been mostly weak because of the utterly dysfunctional process. The good news may be that, in our assessment, this isn’t a European crisis. The bad news is that, well, this is a global crisis. As such, should the process improve, the crisis may target other regions in the world. The U.K., the U.S., and Japan are some of the candidates. Unlike the Eurozone, the U.S. has a current account deficit; as such, the U.S. dollar may be far more vulnerable than the euro has been should the bond market ever be less forgiving about fiscal largess in the U.S. As we have argued for some time, there may not be such a thing as a safe asset and investors may want to take a diversified approach to something as mundane as cash.

As I am wrapping up this analysis, EU Commissioner Barroso is starting a more public campaign for a banking union, suggesting that the biggest banks across the EU submit themselves to a single cross-border supervisor. The Bundesbank is already pushing back, arguing this might equate to a back door Eurobonds.

Please make sure to sign up to our newsletter to be informed as we discuss global dynamics and their impact on currencies. Please also register for our upcoming Webinar on June 13 where we will discuss the investment strategy and objectives of the Merk Absolute Return Currency Fund. We manage the Merk Funds, including the Merk Hard Currency Fund. To learn more about the Funds, please visit www.merkfunds.com.

Axel Merk

Manager of the Merk Hard Currency Fund, Asian Currency Fund, Absolute Return Currency Fund, and Currency Enhanced U.S. Equity Fund, www.merkfunds.com

Axel Merk, President & CIO of Merk Investments, LLC, is an expert on hard money, macro trends and international investing. He is considered an authority on currencies.