While everyone is focused and worried about the news flow from Europe, I am less concerned about the prospects for Greece and the eurozone. As I wrote in my last post (see Draghi, the last domino, falls), Germany is becoming increasingly isolated and expect her to start to bend on the issue of eurobonds. While they may not be eurobonds in the strictest sense, we are likely to see some sort of typical European compromise on Pan-European infrastructure bonds.

I am more concerned about the news flow out of China, which is likely to deteriorate over the next few months - and none of the negative news has been discounted by the market.

The consensus on China

Currently, the consensus view on China is that while the economy is weakening, the authorities are aware of the problem and they are taking steps to remedy the situation. Indeed, Bloomberg reported that Premier Wen Jaibao made some remarks on May 20 suggesting that more stimulus was on the way:

Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao said the government will focus more on bolstering economic growth, indicating policies may be loosened further as inflation moderates.

“The country should properly handle the relationship between maintaining growth, adjusting economic structures and managing inflationary expectations,” Wen said during a tour of Wuhan, the capital of China’s Hubei province, from Friday to Sunday.

“We should continue to implement a proactive fiscal policy and a prudent monetary policy, while giving more priority to maintaining growth,” Wen said.

The market interpreted his comments as being growth friendly:

Wen’s remarks cited in the report, which didn’t mention concern about inflation, indicate the government might take more aggressive steps to support the economy after April data showed the slowdown may be sharper than expected. The central bank this month cut banks’ reserve requirement ratio for the third time since November to boost liquidity.

Take a look at the Shanghai Composite, which reflects this ambiguity about China's near-term growth outlook. The index is currently testing the downside of an unresolved wedge formation, which indicates indecision. A breakout to the upside of the wedge would be interpreted bullishly while a downside breakdown would be bearish.

Turmoil beneath the surface

While the picture of the Shanghai Composite reflects this consensus view, a tour of secondary market indicators suggest that not all is well with the Chinese economy. First of all, the flash PMI release showed contraction.

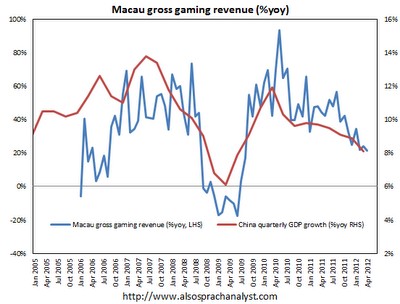

Signs of economic weakness are everywhere, this analysis shows a a tight correlation between Macau gaming revenues and Chinese growth - and gaming revenues are falling.

Next door in Hong Kong, the Hang Seng Index is not behaving quite as well as the Shanghai Composite. The index rallied in February to fill the downside gap that occurred in August 2011, but the rally couldn't overcome resistance. The index has now violated an important support zone and weakening rapidly.

Further north from Hong Kong, South Korea is an economy that is highly sensitive to global economic cycle. In particular, the South Koreans export a lot of capital equipment and other goods to China. That country's stock market isn't behaving well either. In fact, it's cratering.

China has been an enormous consumer of commodities. Commodity prices have also been weakening as the CRB Index is in a downtrend and has violated an important support level.

Australia is not only a major commodity exporter, it is highly sensitive to Chinese commodity demand because of its geography. The AUDUSD exchange rate is falling rapidly.

Just to show how bad things are, the Canadian economy is similar in characteristic to Australia's. Both are industrialized countries that are large commodity exporters. The only difference is that Australia is more levered to China, whereas

Canada is more sensitive to US growth. Take a look at the AUDCAD cross rate as a measure of the forward expectations between the level of change in Chinese and American growth.

Is the shadow banking system unraveling?

The story that I have outlined so far is the story of economic deceleration in China. There is another risk that the market doesn't seem to be focusing on - the risk of a Lehman-like catastrophe in China's financial system. Patrick Chovanec, a professor at Tsinghua University's School of Economics and Management in Beijing, writes:

There really are two related but distinct things people have in mind when they talk about a “hard landing” for China. The first is a rapid deceleration of GDP growth – below, say, 7%. The second is some kind of financial crisis. I think we’re already seeing some signs of the first, and the second is a bigger risk than most people appreciate.

He went on to detail an incident of how the shadow banking system is unraveling in China:

In early April, Caixin magazine ran an article titled “Fool’s Gold Behind Beijing Loan Guarantees”, which documented the silent implosion of Zhongdan Investment Credit Guarantee Co. Ltd., based in China’s capital. “What’s a credit guarantee company?” you might ask — and ask you should, because these companies and the risks they potentially pose are one of the least understood aspects of China’s “shadow banking” system. If the risky trust products and wealth funds that Caixin documented last July are China’s equivalent to CDOs, then credit guarantee companies are China’s version of AIG.

As I understand it, credit guarantee companies were originally created to help Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) get access to bank loans. State-run banks are often reluctant to lend to private companies that do not have the hard assets (such as land) or implicit government backing that State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) enjoy. Local governments encouraged the formation of a new kind of financial entity, which would charge prospective borrowers a fee and, in exchange, serve as a guarantor to the bank, pledging to pay for any losses in the event of a default. Having transferred the risk onto someone else’s shoulders, the bank could rest easy and issue the loan (which it otherwise would have been reluctant to make). In effect, the “credit guarantee” company had sold insurance — otherwise known as a credit default swap (CDS) — to the bank for a risky loan, with the borrower forking over the premium.

OK, so China has a bunch of little AIGs. The story gets better, you have leverage on top of leverage [emphasis added]:

Zhongdan, the company in the Caixin article, took these risks one step further. It persuaded borrowers to take out bank loans based on guarantees from Zhongdan, and then hand some or all of that money back to Zhongdan to invest in Zhongdan’s own “wealth management” products:

Under the arrangement, a participating company would take out a bank loan and give some of the money to Zhongdan for investing in high interest-paying wealth management products for a month or more.

The firm then apparently put those funds to work by buying stakes in small companies such as pawnshops and investment consulting firms, according to the sources. Some of the funds went toward a U.S. consultancy that later failed.

When excesses occurred in the US with subprime lending and "liar loans", rules were skirted. It's no different in China.

Since this use of funds completely violated banking rules, Zhongdan forged documents indicating the money was being borrowed to pay fictitious suppliers:

To nail one loan, [an executive for a building materials manufacturer] said, Zhongdan formed a shell building materials supplier and wrote a fake contract between the supplier and his company. The document was presented to the bank, which approved the loan. Zhongdan later de-registered the phony supplier.

It all unraveled in the end.

The whole thing started to unravel in January when banks “reacted to rumors of a liquidity crunch” at Zhongdan:

At that point, regulators stepped in and told everybody to freeze — and to keep all the assets as “good” on everyone’s balance sheets while they figured out what to do next. Zhongdan had over 300 clients, and guaranteed RMB 3.3 billion (US$ 521 million) in loans from at least 18 banks. The only liquid assets that the guarantee company appears to have available to pay banks is RMB 210 million (US$ 33 million) in margin accounts deposited with the banks themselves. Good luck finding the rest:

Several banks that cooperated with Zhongdan smelled trouble and started calling loans they had issued to companies backed by the firm … The next domino fell when the creditor companies, seeking to appease the banks, turned to Zhongdan for help repaying the called loans. But Zhongdan executives balked, and the domino effect accelerated as companies teetered under bank pressure and the city’s business community shuddered with credit freeze fears.

When I hear stories like this, I think of the cockroach theory. If you see one cockroach, there are sure to be more.

Reuters recently reported a story that Chinese buyers were defaulting on coal and iron ore shipments. While this story may be an indication of a slowing economy in China and slackening commodity demand, it might have stopped there. But the story gets worse as it exposes the cracks in the shadow banking system. It turns out that Chinese buyers have been buying commodities and using them as collateral to obtain financing. When the economy and commodity prices turned down, they were caught. This type of financing is highly prevalent in the copper market, as Reuters reported that Chinese warehouse were so full that copper inventory was the red metal was being stored in car parks.

Watching the shadow banking system

I have no idea what all this means. China's economy is highly opaque and we have no reliable statistics. How big is the shadow banking system and how much leverage is involved? We know that there are problems, but I have no way of quantifying it.

Could this result in a crash landing, i.e. negative GDP growth, in China? I have no idea. Certainly, the unraveling of excessive leverage has seen that kind of result before.

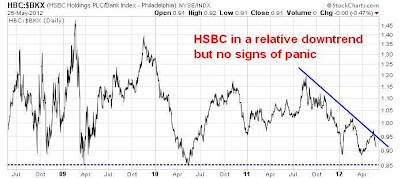

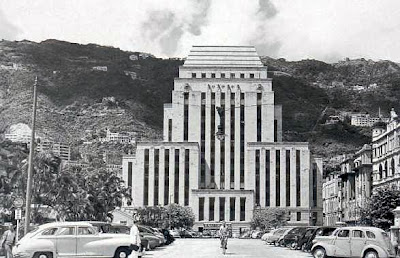

Here is one offbeat way that I am watching for signs of stress in China's shadow banking system. I am watching the share price of HSBC. While HSBC is a global bank, it has deep roots in Hong Kong and Asia. For newbies, HSBC stands for Hongkong Shanghai Banking Company. It is a bank that was firmly established in Hong Kong. As a child, I can remember driving by the bank's headquarters in downtown Hong Kong in the 1960's.

Stresses in the Chinese financial system is likely to show up in the share price of major financials that have exposure to China and Asia, like HSBC. The stock has been falling rapidly in the past couple of weeks, which is not a good sign.

To put the stock performance into context, I charted the performance of the stock relative to the BKX, or the index of US bank stocks. HSBC has been in a relative downtrend, but the lows of 2009 have not been violated. I interpret this as the market signaling that while there may be signs of trouble, it is not panicking.

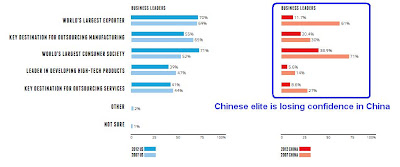

Chinese elite losing confidence

To add to China's troubles, the Chinese business elite is starting to lose confidence in China's long-term outlook. FT Alphaville highlighted a survey by the Committee of 100, an international, non-profit, non-partisan membership organization that brings a Chinese American perspective to issues concerning Asian Americans and U.S.-China relations. The results of this key question asks American and Chinese business leaders their outlook for China. While Americans believe that

Chinese growth will continue long into the future, the Chinese are far less optimistic and their outlook has deteriorated rapidly since 2007.

China's outlook in 20 years

Putting it all together, we have signs of a weakening economy, a shadow banking system that is teetering and a loss of confidence by China's business elite. While the government is taking steps to address the problems, none of these risks have been discounted by the market.

While I expect the news flow from Europe to improve in the days to come, which is bullish, I also expect further stories of deterioration out of China, which has the potential to be extremely bearish. All this points to further choppiness in stocks and risky assets with a downward bias.

Cam Hui is a portfolio manager at Qwest Investment Fund Management Ltd. ("Qwest"). This article is prepared by Mr. Hui as an outside business activity. As such, Qwest does not review or approve materials presented herein. The opinions and any recommendations expressed in this blog are those of the author and do not reflect the opinions or recommendations of Qwest.

None of the information or opinions expressed in this blog constitutes a solicitation for the purchase or sale of any security or other instrument. Nothing in this article constitutes investment advice and any recommendations that may be contained herein have not been based upon a consideration of the investment objectives, financial situation or particular needs of any specific recipient. Any purchase or sale activity in any securities or other instrument should be based upon your own analysis and conclusions. Past performance is not indicative of future results. Either Qwest or Mr. Hui may hold or control long or short positions in the securities or instruments mentioned.