Facebook Aside, Everyone Who Thinks IPO "Pops" Are Good Has Been Brainwashed

Guest post by Henry Blodget, The Business Insider

Last Friday, after Facebook stock started trading at $42, most observers immediately pronounced the IPO a flop.

Last Friday, after Facebook stock started trading at $42, most observers immediately pronounced the IPO a flop.

Why?

Because the IPO had been priced at $38, which meant that the IPO "pop" was only about 10% above the IPO price.

Facebook stockholders who had bought the IPO the night before had instantly made 10% overnight--a spectacular return. String together a few months of daily returns like that, and you would quickly be one of the most successful investors in history.

But some Facebook speculators had expected to make much more free money overnight--perhaps as much as speculators in LinkedIn and other hot IPOs had made.

So they felt disappointed and ripped off.

And the media, who have been carefully trained by Wall Street and short-term speculators to view IPOs with big pops as "successful" and IPOs with small or no pops as "flops" immediately dissed Facebook as a flop.

Now, there were two serious issues with the Facebook IPO that complicate any discussion focused on this IPO in particular: The NASDAQ screwup that borked at least a day's worth of trading, and the "selective disclosure" scandal, in which the underwriters told their big clients that Facebook's second quarter was weak but did not tell their small clients this.

Both of those issues may well have affected Facebook's first day of trading and contributed to the subsequent price decline. And both of those issues are legitimate sources of frustration, for investors and the company alike. (So please don't bother raising these issues in the comments below: They're separate and apart from the point of this discussion, which is about first-day "pops.")

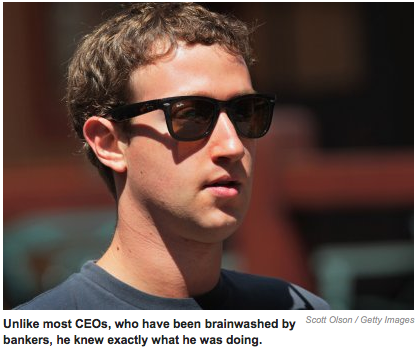

According to a source very close to the situation, all other issues aside, Facebook was aiming for a 10% pop. Not a 25% pop. Not a 50% pop. A 10% pop. And for most of the first day of trading, that's exactly what Facebook got. In other words, Facebook did exactly what it was hoping to do.

Facebook knew well how this 10% pop would be perceived by the media: As a disappointment.

But Facebook understood what most companies that go public don't:

- Any press grumbling about "disappointments" and "small pops" will be quickly forgotten.

- The only investors who benefit from "pops" are short-term flippers who won't help the company long term and don't deserve free money

- "Pops" cost the company and its existing shareholders hundreds of milions of dollars (in Facebook's case, billions)

- "Pops provide no advantage to the company other than a bit of extremely expensive and ephemeral excitement and PR

- Pricing the IPO high enough to have only a small pop meant raising millions or billions more dollars that would subsequently be worth milions or billions of dollars to the company

Specifically, in Facebook's case, if Facebook had priced the IPO at, say, $30, instead of $38, it would have raised ~$12.5 billion in the IPO instead of $16 billion.

In exchange for a bigger "pop," happier speculators, and a more enthusiastic press reception, in other words, Facebook and its selling shareholders would have sacrificed $3.5 billion that they can now use to create real value for the company and its shareholders (including its new shareholders).

$3.5 billion is real money.

AP/Android Police

Another CEO who understands the truth about IPO pops.

Blowing $3.5 billion on making speculators and financial reporters happier would have been the height of short-term thinking. And, like other great companies, Facebook doesn't make decisions aimed at creating short-term value. It makes decisions designed to create long-term value.

The extra $3.5 billion Facebook raised by aiming for 10% pop will create at least $3.45 billion more value for Facebook over the long term than a bigger "pop" would have. (The short-term press hyperventilation and speculator euphoria may create some value for a company, but not much. And it may even be harmful to the company by making everything after the IPO seem like an anti-climax.)

But, but, but!

What about the IPO investors?

Shouldn't Facebook and other IPO companies want to make investors happy?

Shouldn't they be less greedy and give investors a reward for taking a chance on them?

Yes.

IPOs should not be priced "at market value." They should be priced just below market value This rewards initial investors for taking the chance on the IPO pricing (which is always risky--no one knows exactly what "market value" will be). And it gives the investors an incentive necessary to do the research on the company before it goes public. Without that, the investors might just wait to see where the stock traded and do the research then.

But any investor who thinks they need more than a 5%-10% overnight return as a reward for placing an order on the IPO is unbelievably greedy.

Again, a 10% return overnight is a spectacular return.

A 10%-20% return, which is what early-stage IPOs should aim for, is an even more spectacular return.

So any investor who thinks they deserve more than that is just greedy.

But What About "Broken IPOs" -- They're Terrible, Right? [No]

What if the "market value" for a company on the first day of trading is higher than a conservative market value that a conservative investor would place on it? What if the stock drops below the IPO price after the first couple days of trading? What if the company has a "broken IPO?"

Yes, what about that.

This is where Wall Street's brainwashing of clients and the media about IPOs has been most insidious and effective.

So, really, what if a company has a "broken IPO?" Isn't that a huge disaster?

No.

In fact, it's hardly worth mentioning.

What it means is that investors who placed orders for the IPO at certain prices and were intending to hold the stock for more than the first day of trading and were unwilling to tolerate a drop below the IPO price were too aggressive in their bids.

www.naismithhome.com

You're selling your house. Should you sell it at 25% or off just to create a "pop"? Of course not!

That's the investors' fault, not the company's fault. And the resulting disappointment and disgruntlement is called "buyers' remorse." And it happens all the time, in almost every industry and type of transaction on the planet.

Let's use a real-estate analogy.