by Sai S. Devabhaktuni, and Gregory Kennedy, PIMCO

May 2012

- With the exception of LNG tankers, all three major shipping categories have been suffering from a supply glut. This, combined with higher fuel costs, has led many shipping companies into financial distress.

- Although banks have worked with ship owners through this down cycle, they have also pulled back from financing the industry.

- Given the current low point in the cycle, we believe downside risks are likely minimized in the shipping industry for new lenders and investors. Vessel values are depressed by rates that are sometimes below owners' operating costs and by an oversupplied market that suppresses secondary market values.

In spite of the current woes in the shipping industry, including a significant erosion of value and a glut of new vessels, we see the potential for a brighter future on the distant horizon – especially as the order book of new vessels begins to shrink and emerging market growth provides a much-needed driver of demand.

As a result, select opportunities to buy the debt of operators or to buy portfolios of vessels at prices below their intrinsic value are now available to informed investors – and could offer attractive long-term returns. Capitalizing on this anticipated rebound, however, requires patience, dedicated long-term capital and a strong understanding of industry fundamentals and maritime restructuring dynamics. These waters demand careful navigation.

A brief history of the voyage to today’s market

The global shipping industry is in the midst of its worst cycle since the 1980s. A recent Bloomberg article highlighted that “the combined market value of the world’s 80 biggest publicly traded shipping companies plunged by $101.7 billion in the four years to March 23, 2012.” What caused so much value destruction? The combination of an excess supply of new vessels that were financed at the peak of the market and a global recession from which there has been an uneven recovery has led to persistently low charter rates and plummeting ship values. In its wake is nearly $500 billion of debt, the overwhelming majority of which is held by European banks.

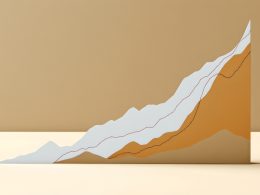

Over 90% of world trade activity depends on the shipping industry’s global fleet of 58,000 ships, according to Clarksons and J.P. Morgan. The fleet includes tankers, dry bulk ships, container ships, chemical tankers, liquefied natural gas (LNG) tankers and other cargo ships across what is a highly fragmented industry. As the global economy expanded and international trade increased after the end of the Cold War, world seaborne trade increased by nearly 50% from 1990 to 2000, from about four billion tonnes to six billion tonnes annually, which helped the shipping industry recover from the vessel oversupply it faced in the 1980s (see Figure 1).

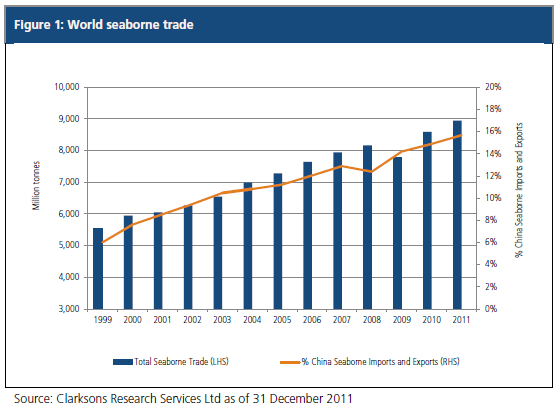

The global shipping industry has long cycles and was historically driven by demand and GDP growth in developed economies. But by 2003, demand from emerging economies like China began accelerating, which pushed global seaborne trade to over eight billion tonnes by 2008. China’s demand for coal and iron increased nearly 20% per year from 2004 to 2011, and the country is now a net importer rather than exporter of coal. This insatiable emerging market demand, combined with increased prosperity due in part to the credit bubble in developed markets, led to a vessel shortage, driving shipping rates to new highs (see Figure 2).

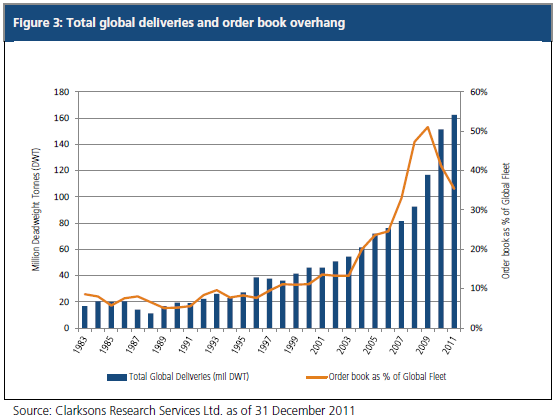

The shipping industry responded to these historically high shipping rates by ordering what turned out to be an excessive number of vessels. From 2003 to 2008, over $800 billion of new ships were ordered, with half of the orders placed in 2007–2008, when vessel prices were at their peak, according to Clarksons. During these boom years, bank lending was widely available for new ships, as banks offered financing of up to 80% loan-to-value (LTV) for new vessels (versus 50% to 60% today), leaving little margin for error in vessel values. Most of those vessels were scheduled for delivery in the years immediately following the financial crisis of 2008–2009, compounding the oversupply issue.

Rough seas follow the expansion

As a result of the order book overhang resulting from overly optimistic expectations of demand (i.e., volume) growth, shipping rates have faced persistent headwinds from net new vessel deliveries at about twice the rate of shipping demand growth during the recovery of the past few years (see Figure 3). With the exception of the under-fleeted LNG tanker market, all three major shipping categories (bulkers, tankers, containers) have been suffering from a supply glut. This, combined with higher fuel costs, has led many shipping companies into financial distress.

Because of new vessel deliveries over the past three to four years, the global fleet is fairly young, which means there are not as many older ships available that would typically make economic sense to scrap. And while delivery slippage of the order book and cancellations help to slow the supply of new vessels entering the market, there is an incentive for shipyards to maintain their order backlog.