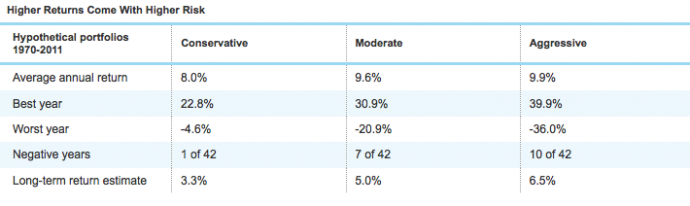

As you can see in the table below, "Higher Returns Come With Higher Risk," since 1970, an aggressive investor would have earned a 9.9% annualized return versus an 8.0% annualized return for a conservative investor. Who wouldn't want the higher return? Well, it depends on the risk you're willing to take to get there. What this table further shows is that the 9.9% return came within a much wider range of annual returns and, most importantly, was generated only through "stick-to-it-iveness."

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research hypothetical portfolios2 as of December 31, 2011. For more information on the methodology for the long-term return estimate calculations, see "Q&A: Estimating Long-Term Market Returns." Past performance is no indication of future results.

The aggressive investor had to suffer 10 down years, one of which generated a portfolio loss of 36%. Many investors have learned the hard way that their tolerance for a big loss in a year was less than they thought. And to maintain that aggressive allocation, you generally have to rebalance in favor of the asset class(es) that generated those steep losses and away from those asset class(es) that had weathered the storm.

We believe that rebalancing to maintain an aggressive allocation is the best way to generate the higher return. That, of course, is the real test—a test that is administered more often during times of increased volatility. Here's a practical way to think about rebalancing: Your portfolio will tell you when it's time to trim from or add to an asset class. You don't need to rely on anyone's forecast of what may or may not happen.

Now let's take the conservative investor. Your average annual return after 42 years is just 8.0%, but you only had to suffer one losing year, even though your best year paled in comparison to the aggressive investor's best year. For some, it's worth the lower return for the sleep-at-night benefits.

Market timing: a dangerous game

It's enticing to try to "catch" the next big investment wave (up or down) and allocate assets accordingly. But there are very few time-tested tools for consistently making those decisions well. Unfortunately, rearview mirror investing—or performance chasing—never seems to go out of style.

We did an interesting historical study of investor behavior. In the chart below, you can see the difference between mutual-fund returns and investor returns in those same funds.

The fund return represents the official time-weighted return as reported by the funds themselves. It does not consider the effect of deposits and withdrawals. It measured the performance that would have been earned by an investor who bought at the start of a period and held all the way to the end.

The investor return represents the dollar-weighted return as calculated by Morningstar. It measures the performance of all dollars invested in the funds, including the timing of deposits and withdrawals. As such, it captures a truer picture of what investors actually earn on the dollar in aggregate.

Many investors think they can do better by waiting until the next "perfect" time to buy or sell. Their track record tells us that they're generally wrong. Investors tend to pile in after a fund gets hot and then sell or stop investing after the fund has gone cold or the market has dropped significantly.

The gap between fund return and investor return measures how much worse investors did by moving in and out of funds than they would have with a buy-and-hold strategy. The gap for the recent 10-year period is 2.0% per year, totaling a cumulative 30.9%. Investors gave up more than a third of the total cumulative return due to poor timing.

Although the chart is as of December 31, 2011, we looked at other 10-year periods, as well. The average investor consistently earned less than the average fund.

Decent Fund Returns … Lower Investor Returns

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research with data from Morningstar, Inc., as of December 31, 2011. Fund return is the weighted average time-weighted return of all active funds in the Morningstar domestic equity, specialty, and international stock categories. Each fund is represented by its oldest share class. Investor return for each fund is calculated by Morningstar and reflects the average return on all dollars invested based on estimated monthly net fund flows. The aggregate investor return and fund return are averages weighted by the size of each fund. Only funds with both the fund return and the investor return are included in the analysis. Past performance is no indication of future results.

Time horizons: the longer, the better

Based on several well-known studies, the length of time that individual investors hold stocks and mutual funds has shrunk precipitously over the past 50 years. Back then it was common for investors to have five-to-10 year time horizons, but today it's typically well less than a year. And the trigger for selling and/or buying is often short-term performance chasing: buying recent hot-performing funds or asset classes and running from recent losers.

In the chart below, "Longer Time Horizon = Lower Downside Risk," you can see the power of long holding periods when it comes to minimizing downside risk. The longer you extend your time horizon, the less likely you'll experience a loss over that holding period.

Longer Time Horizon = Lower Downside Risk

Source: Schwab Center for Financial Research with data provided by Standard and Poor's. Every one-, three-, five-, 10- and 20-year rolling calendar period for the S&P 500® Index was analyzed from 1926 through 2011. The highest and lowest annual total returns for the specified rolling time periods were chosen to depict the volatility of the market. Returns include reinvestment of dividends. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur fees or expenses, and cannot be invested in directly. Past performance is no indication of future results.

Patience and stick-to-it-iveness

Admittedly, the development of a long-term strategic asset allocation plan isn't the hard part—it's sticking to it that often becomes the real challenge. We think that the best way for an aggressive investor to have generated the 9.9% annualized return since 1970 was for that investor to have remained aggressive throughout the period, including during 10 down years. That meant rebalancing, typically in favor of underperforming asset classes and away from outperforming asset classes. The same goes for the rebalancing associated with maintaining a conservative allocation.

Adding to underperforming asset classes and trimming outperforming asset classes goes against the emotions of fear and greed that often drive investment decision making. But if we learn from our mistakes, use our brains over our hearts and look to our portfolios as rebalancing guides, we can expect a more successful investing future and maybe even get a free lunch along the way.

1. See Schwab.com/portfoliocheckup for five strategic asset allocation models, including Moderately Conservative and Moderately Aggressive.

2. Data from Morningstar, Inc. The return figures for 1970 through 2011 are the average, the minimum and the maximum annual returns of the hypothetical asset allocation plans, The asset-allocation plans are weighted averages of the performance of the indices used to represent each asset class in the plans, include reinvestment of dividends, and are rebalanced annually.The indexes representing each asset class in the historical asset allocation plans are S&P 500 index (large-cap stocks), Russell 2000® Index (small-cap stocks), MSCI EAFE® Net of Taxes (international stocks), Barclays US Aggregate Bond Index (fixed income) and Citigroup Three-Month Treasury Bills (cash investments). CRSP 6-8 was used for small-cap stocks prior to 1979, Ibbotson Intermediate-Term Government Bond Index was used for bonds prior to 1976, and Ibbotson US 30-Day Treasury Bill were used for cash investments prior to 1978. Indexes are unmanaged, do not incur fees or expenses and cannot be invested in directly. Past results are not indicative of future performance.

Copyright © Schwab.com