In other words, in most regards the capital markets – and investors’ tolerance of risk – are retracing their steps back in the direction of the bubble-ish pre-crisis years. Low yields, declining yield spreads, rising leverage ratios, payment-in-kind bonds, covenant-lite debt, increasing levels of LBO activity and the beginnings of the return of levered, structured vehicles . . . all of these are available for the eye to see.

For a case in point, let me recap a note I received from one of our veteran high yield bond analysts regarding a deal that recently had come to market:

- PIK/toggle bonds: the company can elect to pay interest in debt rather than cash

- Holdco obligation: debt of a holding company, removed from the moneymaking assets

- Use of proceeds: to pay a dividend to the equity sponsor, returning half of the equity it put into the company just a few months earlier

- The sponsor’s purchase price for the company in 2010 was 1.45 times what the seller had bought it for in 2008

- The company operates in a commodity industry where annual sales are shrinking and costs are variable and unpredictable

- Negative earnings comparisons are expected, since the environment makes it hard to pass on rising raw material costs

- EBITDA coverage of interest expense plus capital expenditures is modestly above 1x

- The company is incorporated in Luxembourg, an uncertain bankruptcy environment

- The assessment of Oaktree’s Sheldon Stone: “I know they don’t ring a bell at the top, but they should on this deal!”

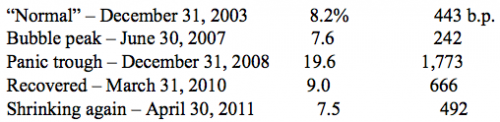

It’s easy to gauge bond investors’ attitudes. Here are the yield to maturity and yield spread versus Treasurys on the average high yield bond at a few points in the recent past and today:

Yield to Spread vs.

Maturity Treasurys

The yield spread on the average high yield bond is still on the generous side relative to the 30-year norm of 350-550 basis points, a range of spreads that has given rise to excellent relative returns over that period. On the other hand, (a) spreads have fallen back to the normal range from the crisis-induced stratosphere and (b) the lowness of today’s interest rates means that reasonable spreads translate into promised returns that are low in the absolute. The story’s the same for many asset classes.

I don’t mean to pick on high yield bonds. I use them here as my prime example only because of my familiarity with them and because their fixed-income status facilitates quantification of attitudes toward risk. In fact, high yield bonds still deliver above average risk compensation, and they remain the highest returning contractual instruments and excellent diversifiers versus high grade bonds.

If you refer back to a memo called “Risk and Return Today” (November 2004), you’ll see that today’s expected returns and risk premiums – especially on the left-hand side of the risk/return spectrum – are eerily similar to those prevailing in late 2004: money market at 1%; 5-year Treasurys at 3%; high grade bonds at 5%; high yield bonds at 7%; stocks expected to return 6-7%. I said at the time that low base interest rates and moderate demanded risk premiums had combined to render the risk/return curve “low and flat.” In other words, absolute prospective returns were at modest levels, as were the return increments that could be expected for taking on incremental risk. I described that environment as “a low-return world.” I think we’re largely back there.

(Please note that late 2004 was nowhere near the cyclical peak. Security prices continued to rise and prospective returns to fall for two and a half years thereafter. In particular, in the 30 months following the publication of that memo, high yield bonds went on to return a total of 19.7%. So similarities to 2004 don’t constitute a sign of impending doom, but perhaps a foreshadowing of a potential move into bubble territory.)

I want to state very clearly that I do not believe security prices have returned to the 2006-07 peaks. It doesn’t feel like the silly season is back in full. Investors aren’t euphoric. Rather they seem like what my late father-in-law used to call “handcuff volunteers” – people who do things because they have no choice. They’re also not oblivious to the risks that exist. I imagine the typical investor as saying, “I’m not happy, but I have to buy it.” Finally, the leverage used at the peak of risk-prone pursuit of return in 2005-07 isn’t nearly as prevalent today, perhaps because investors are chastened, but more likely because it’s not available in the same amounts.

There may be corners of the market where elevated popularity and enthusiastic buying have caused prices to move beyond reason: high-tech stocks, social networks, emerging markets from time to time, perhaps gold and other commodities (what’s the reasonable price for a non-cash-flow-producing asset?) But for the most part, I think investors are taking the least risk they can while assembling portfolios that they think can achieve their needed returns or actuarial assumptions.

In general, I would describe most security prices as falling somewhere between fair and full. Not necessarily bubbly, but also not cheap.

Especially since the publication of my book, people have been asking me for the secret to risk control. “Okay, I’ll read the 180 pages. But what’s really the most important thing?” If I had to identify a single key to consistently successful investing, I’d say it’s “cheapness.” Buying at low prices relative to intrinsic value (rigorously and conservatively derived) holds the key to earning dependably high returns, limiting risk and minimizing losses. It’s not the only thing that matters – obviously – but it’s something for which there is no substitute. Without doing the above, “investing” moves closer to “speculating,” a much less dependable activity. When investors are serene or even euphoric, rather than discomforted, prices rise and we become less likely to find the bargains we want.

So if you could ask just one question regarding an individual security, asset class or market, it should be “is it cheap?” Oaktree’s investment professionals try to ask it, in different ways, every day.

And what makes for cheapness? In sum, the attitudes and behavior of others.

I try to get away from it, but I can’t. The quote I return to most often in these memos, even 17 years after the first time, is another from Warren Buffett: “The less prudence with which others conduct their affairs, the greater prudence with which we should conduct our own affairs.” When others are paralyzed by fear, we can be aggressive. But when others are unafraid, we should tread with the utmost caution. Other people’s fearlessness invariably translates into inflated prices, depressed potential returns and elevated risk.