by William Smead, Smead Capital Management

We are great admirers of the writing of the elite business publications like The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. They recently stepped into one of our favorite subjects, technology company hegemony, which has developed in the business world in recent years. Here is Webster’s definition of hegemony:1

Hegemony. 1 : preponderant influence or authority over others : domination 2 : the social, cultural, ideological, or economic influence exerted by a dominant group.

On January 4, 2017, The New York Times writer, Farhad Manjoo, wrote a story titled, “Tech Giants Seem Invincible. That Worries Lawmakers.” He has taken to calling today’s dominant tech behemoths the “Frightful Five” (Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Google and Microsoft). He argues that the process of smaller tech companies emerging to ruin things for the biggest and strongest has been interrupted.

Then, in the last half decade, something strange happened: The sharks began to get bigger and smarter. Nearly a year ago, I argued that we were witnessing a new era in the tech business, one that is typified less by the storied start-up in a garage than by a posse I like to call the Frightful Five: Amazon, Apple, Facebook, Microsoft and Alphabet, Google’s parent company.

Together the Five compose a new superclass of American corporate might. For much of last year, their further rise and domination over the rest of the global economy looked not just plausible, but also maybe even probable.2

We have a particularly good perch to view technology hegemony, because our company is 10-12 blocks from Amazon’s main campus and 10 miles away from the Microsoft campus in Redmond. Some people are calling us “Cloud City,” because of the domination of Amazon and Microsoft in cloud computing. Is it beneficial for massive quantities of invested capital to concentrate in one sector of the S&P 500 Index? What does history tell us about whether this is going to be good for investors and good for the U.S. economy?

Maureen Farrell, writing in The Wall Street Journal, showed us why smaller tech companies are not drawing interest away from the “Frightful Five” in the public stock market. Her article titled “Investors Lament: Fewer Public Listings” on January 5, 2017 pointed out that there are 3,000 fewer public companies in the U.S. than in 1997. She also argued that the wealthiest and most elite investors are being given entrée to ownership of the most interesting and exciting technology companies which are in the tradable private market.

The U.S. is becoming “de-equitized,” putting some of the best investing prospects out of the reach of ordinary Americans. The stock market once offered a way for average investors to buy into the fastest-growing companies, helping spread the nation’s wealth. Since the financial crisis, the equity market has become bifurcated, with a private option available to select investors and a public one that is more of a last resort for companies.3

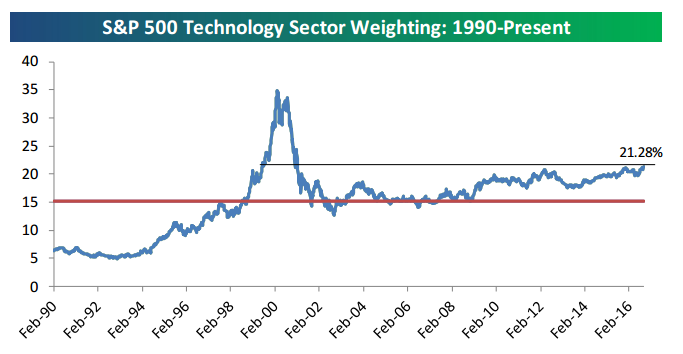

She proposes that the dearth of new supply among tech stocks for public investors has inflated what investors will pay to own the ones which are available. Nobody seems more available than the “Frightful Five,” who seem to have invaded and are controlling an unusually large part of our economic life. As a result of the concentration in the “Frightful Five” and the ongoing love affair with all things tech on Wall Street, the S&P 500 Index is a historically and dangerously large owner of technology. Remember, Amazon and Netflix are not included in the tech sector of the S&P 500.

In her “Investors’ Lament” article, she pointed out how much capital is tied up in the private market in today’s so called “unicorn” companies:

Venture-capitalist Bill Gurley sees a bubble in the private markets. He predicts investors will lose significant amounts in many closely held companies valued at $1 billion or more, which currently stand at 154, according to Dow Jones VentureSource. “History would suggest that it’s a real possibility,” he says.

This bubble in private companies is being fed by the proliferation of sovereign wealth and private-equity funds. Those pools of capital have grown from $2 trillion in 2004 to near $9 trillion in 2015 and have fed the privately-held tech companies like Uber, Lyft and Airbnb. Imagine what the S&P 500 tech holdings would look like if these huge market cap “unicorns” were already in the index!

As veterans of the U.S. stock market in the late 1990’s, we remember the tech bubble very well. It played out locally in Seattle in a binge of home building by tech executives on the shores of Lake Washington. They attempted to create their own version of the Newport, Rhode Island mansions on the shores of the Atlantic built by the wealthiest barons of industry in 1900.

Currently, we see some of the economic implications of tech hegemony in the local economy. THERE ARE 40% MORE LARGE BUILDING CRANES OPERATED IN THE CITY OF SEATTLE THAN ANY OTHER CITY IN THE U.S. Those cranes are building office space for Amazon, Facebook and Google, as well as apartment buildings near their local campus to house their employees. Facebook is reported to be spending $200 per square foot to renovate an existing building for their employees in Seattle. Housing is in very short supply and out of the reach of the vast majority of families which live in the Puget Sound region.

Where does this take us? We are willing to bet that tech will have its problems in the future like it has had in the past. When Apple and Genentech went public in the early 1980’s and inflation was running rampant, the stock market adored tech stocks. By 1990, the S&P 500 Index only had 7% of its market cap in tech. Tech is dominating the index in a way that is only rivaled in recent history by the insanity of the tech bubble which broke in 2000.

On a local basis and in cities like San Francisco and Palo Alto, city planners better start thinking about what life would look like if the success of technology companies reverts to the historical norms, or if the “unicorns” come public in need of capital and dilute the “Frightful Five.” The most damning words in investing are, “It’s different this time.” Buyers beware.

Warm Regards,

William Smead

1Source: Merriam-Webster

2Source: The New York Times

3Source: Wall Street Journal

The information contained in this missive represents Smead Capital Management’s opinions, and should not be construed as personalized or individualized investment advice and are subject to change. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Bill Smead, CIO and CEO, wrote this article. It should not be assumed that investing in any securities mentioned above will or will not be profitable. Portfolio composition is subject to change at any time and references to specific securities, industries and sectors in this letter are not recommendations to purchase or sell any particular security. Current and future portfolio holdings are subject to risk. In preparing this document, SCM has relied upon and assumed, without independent verification, the accuracy and completeness of all information available from public sources. A list of all recommendations made by Smead Capital Management within the past twelve-month period is available upon request.

© 2016 Smead Capital Management, Inc. All rights reserved.